When I was 16, I read “First Love,” by Vladimir Nabokov. He describes a trip on the Nord Express train, which went from St. Petersburg to Paris. “I would put myself to sleep by the simple act of identifying myself with the engine driver,” Nabokov wrote. And then comes a dream. “In my sleep, I would see something totally different—a glass marble rolling under a grand piano or a toy engine lying on its side with its wheels still working gamely.” That glass marble rolling under the grand piano made me want to be a writer.

Nabokov is one of the great dreamers, the great lost-time recapturers, of the twentieth century, and Speak, Memory, his autobiography, where the marble passage appears in book form, is, I think, his masterpiece. Another section of the book, “Portrait of My Uncle,” has a strikingly beautiful ending: “The mirror brims with brightness; a bumblebee has entered the room and bumps against the ceiling. Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.” This is Nabokov at his best: full of love and heartbreak—not arrogant and summarily dismissive, not weirdly transfixed as he sometimes was by skin blemishes (wens, warts, and hairy moles)—a man who, though he had lost his country, was recreating it now as if at a picnic in a park on the family estate near St. Petersburg, unfurling a blanket of hyperrealistic description on which he set out the long-lost but freshly burnished soup spoons and ladles of his Russian childhood, a “stereoscopic dreamland” wherein certain specific sunsets and windowscapes and birch-dappled garden pathways still existed and would always exist, rendering the terrible dislocations of totalitarian violence irrelevant.

“I have ransacked my oldest dreams for keys and clues,” Nabokov wrote in this autobiography, and to good purpose: In the long paragraphs of Speak, Memory, every brimming mirror-flash glows eternally, and no spiraling subparticle of one’s life is ever truly lost. “I confess I do not believe in time,” Nabokov wrote. “I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another.”

And here’s a funny thing about that memoir. Speak, Memory was written, so it seems, under the influence of an aeronautical engineer and avid fly fisherman named John W. Dunne. Beginning in the 1920s, Dunne set the literary world on fire with a now more or less forgotten theory of dreams that he termed “serialism.” Actually Dunne’s serialism offered three theories bundled into one—one big, clock-melting, brain-squashing chimichanga of pseudoscientific parapsychology—a theory of time, a theory of immortality, and a theory that dreams could predict the future. Dunne’s book, published in 1927, was called An Experiment With Time, and it went into several editions. “I find it a fantastically interesting book,” wrote H.G. Wells in a huge article in The New York Times. Yeats, Joyce, and Walter de la Mare brooded over its implications, and T.S. Eliot’s publishing firm, Faber, brought the book out in paperback in 1934, right about the time when Eliot was writing “Burnt Norton,” all about how time present is contained in time past and time future, and vice versa.

Dunne’s Experiment seems to have become one of the secret wellsprings, or wormholes, of twentieth-century literature. J.B. Priestley believed that An Experiment With Time was “one of the most curious and perhaps most important books of the age,” and he built several plays around it. C.E.M. Joad, the philosopher and radio personality, said of the book: “It can be recommended to everybody who wishes to learn how to anticipate his own future.” C.S. Lewis wrote a short story, “The Dark Tower,” using Dunne’s ideas. J.R.R. Tolkien found the book helpful as he imagined Middle Earth’s elven dreamtime. Agatha Christie wrote that it gave her a “truer knowledge of serenity than I had ever obtained before.” “Everybody in England is talking about J.W. Dunne, the man who made dreams popular,” reported a newspaper columnist in 1935, though he warned that the innumerable geometrical charts would drive the reader “loco.” Robert Heinlein cited Dunne’s theory in his novella “Elsewhen” in 1941. In 1940, Jorge Luis Borges reviewed the book. “Dunne assures us that in death we will finally learn how to handle eternity,” Borges wrote. “He states that the future, with its details and vicissitudes, already exists.” Dunne brought out several follow-up books to An Experiment With Time. One of them, published in 1940, had a memorable title: Nothing Dies.

Nothing dies, nobody dies, nobody will ever die. Dunne, a slight man with a “good big head,” according to Priestley, believed that everything had already happened and that everybody was immortal—that time was a paradise of somehow slightly spongy simultaneity that was accessible, albeit imperfectly, via a close study, every waking morning, of one’s dreams.

This Aeronautical paraphilosopher developed his theory slowly, over decades. In 1899, the year that Nabokov was born, Dunne dreamed that he was arguing with a waiter about whether it was four-thirty in the afternoon. When he woke, he discovered that his watch had stopped at the very time that he had dreamed that it stopped, four-thirty. Was it a case of clairvoyance? He wasn’t sure. In another dream, he met three weather-beaten men dressed in ragged khaki; one of them told him he’d nearly died of yellow fever in the Sudan. That same morning, he read in The Daily Telegraph that three men had died on an expedition that had just arrived in Khartoum. Hmm, strange.

In 1902, Dunne dreamed of an island that was spouting vapor. “Good Lord,” he said to himself in the dream, “the whole thing is going to blow up!” He opened the Telegraph and saw the news of the explosion of Mount Pelée in Martinique. More quasi-prophetic dreams followed—about 20 of them in all. In 1913, he had a dream in which a train went off the tracks near the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Some months later, the Flying Scotsman leapt the track 15 miles north of the Forth Bridge. “I was suffering,” Dunne concluded, “from some extraordinary fault in my relation to reality, something so uniquely wrong that it compelled me to perceive, at rare intervals, large blocks of otherwise perfectly normal personal experience displaced from their proper positions in Time.” Dunne was, he believed, dreaming the future.

In 1924, he produced a book on the making of semitransparent fishing lures, lures that looked to a fish as if the sun above were shining attractively through them. Then in 1927 came his bombshell, An Experiment With Time—which included dozens of detailed dream descriptions, plus an exceedingly complicated and in parts all-but-unreadable explanation for what he claimed was going on in his good big head, accompanied by a number of elaborate line drawings. His dream prophecies were not, he insisted, the result of voices from the dead or instances of occult or astral communication. No, his dreams were examples of genuine serial “precognition,” arising from his existence as an immortal soul situated as a point of consciousness in a multidimensional, post-relativistic, somehow infinitely regressive and/or nestingly Chinese-boxed field of Time. (Time always has a capital “t” in Dunne’s world.) Here is a sample of Dunne’s temporal geometry:

We conclude stage 2, then, by fitting an arrowhead to Time 2 in the dimension-indicator of Fig. 8, in order to show that GH is a field of presentation moving up Time 2. The motion of field I along Time I is now recovered. For, as GH moves up the diagram, the point O, where GH intersects with O’O”, moves along GH towards H, thus coming upon the cerebral states one after another in succession from left to right.

I bought a used copy of the red Faber edition of An Experiment With Time in 1991, at Abacus Book Shop on Gregory Street in Rochester, New York. Abacus has since moved to Monroe Avenue, but according to Dunne’s theory the bookshop still exists in its old location inside one of the matryoshka dolls of universal Time, with the unbought copy of his book still waiting on the shelf. I didn’t get very far in the book. Dunne writes, of his theory: “Serialism discloses the existence of a reasonable kind of ‘soul’—an individual soul which has a definite beginning in absolute Time—a soul whose immortality, being in other dimensions of Time, does not clash with the obvious ending of the individual in the physiologist’s Time dimension.” His dream prophecies and “Master-minds” and “Superbodies” bewildered me—really they seemed like a fancier way of talking about sibyls and angels and the hierarchy of heaven. And the pseudogeometrical figures, reminiscent of drawings in paperback explications of Einsteinian space-time, seemed—not to be rude—quite nutty.

Somewhere along the twisty path of the twentieth century, Vladimir Nabokov, our brilliant dreamer-in-chief, came into contact with Dunne’s theories of oneiric prophecy and was evidently inspired by them. It’s difficult to know when that happened—but clearly everyone was buzzing about Dunne’s Experiment by the 1930s. In King, Queen, Knave (1928), Nabokov writes of false awakenings in nested dreams, “as if you were rising up from stratum to stratum but never reaching the surface, never emerging into reality.” In The Gift (1938), he describes the infinite freedom of dreams, which clot like blood at the moment of waking. In his 1935 novel Invitation to a Beheading, his narrator explains: “What we call dreams is semi-reality, the promise of reality, a foreglimpse and a whiff of it; that is, they contain, in a very vague, diluted state, more genuine reality than our vaunted waking life which, in its turn, is semi-sleep, an evil drowsiness into which penetrate in grotesque disguise the sounds and sights of the real world, flowing beyond the periphery of the mind.” In his first English-language novel, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941), a woman expresses her impatience at hearing Sebastian recount his dreams, “and the dreams in his dreams, and the dreams in the dreams of his dreams.”

In 1955, in The Times, Graham Greene shocked London by choosing Nabokov’s Lolita, which had just been published in Paris, as one of three books of the year, thereby insulating it from possible prosecution under obscenity laws. The novel became a huge best-seller, and Vladimir and Vera, flush with movie money from Stanley Kubrick, left the United States for Europe. Nabokov met Graham Greene in London and they corresponded. Then, in October 1964, both novelists—in a coincidence that may or may not be astounding (perhaps it was simply the result of a jointly agreed-upon scientific experiment?)—began recording their nightly dream adventures in a manner that closely followed John Dunne’s method of morning-after notation.

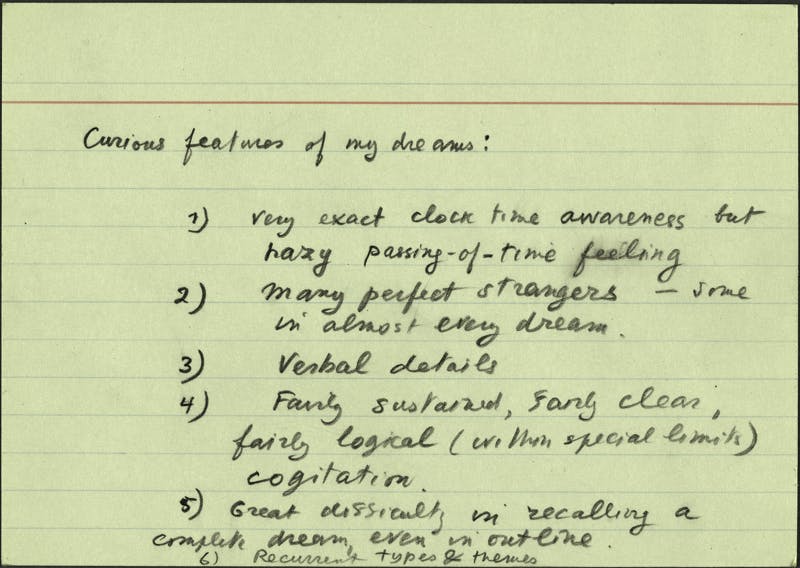

Greene’s dream diary, which he kept up for years, came out in 1994. A World of My Own is a fascinating, revealing book, which makes only a passing mention of Dunne’s Experiment. Nabokov’s dream notes, however—“undertaken,” he writes, “to illustrate the principle of ‘reverse memory’ ” and recorded in pencil on his famous three-by-five cards over a period of several months, during which he referred to Dunne’s book several times—were not published in his lifetime. Only now are they out for everyone to read, swaddled in footnoted commentary and contextual analysis, in a book titled Insomniac Dreams: Experiments With Time by Vladimir Nabokov, edited by Gennady Barabtarlo, a critic and translator who teaches at the University of Missouri.

Barabtarlo does his best to explicate Dunne’s ideas—although he rebels at the many “applied algebraic formulas”—and he includes, in part four of the book, a gorgeous quilt of many-colored passages culled from Nabokov’s lifetime of dream phenomenology and dream paraphrase. There is, for instance, the dream from The Real Life of Sebastian Knight in which Sebastian pulls his glove off: “As it came off, it spilled its only contents—a number of tiny hands, like the front paws of a mouse, mauve-pink and soft—lots of them—and they dropped to the floor,” whereupon a girl dressed in black begins gathering them and putting them in a dish. “All dreams are anagrams of diurnal reality,” Nabokov says in one of his last novels, Transparent Things. The word “dreamy” appears ten times, by my count, in Lolita.

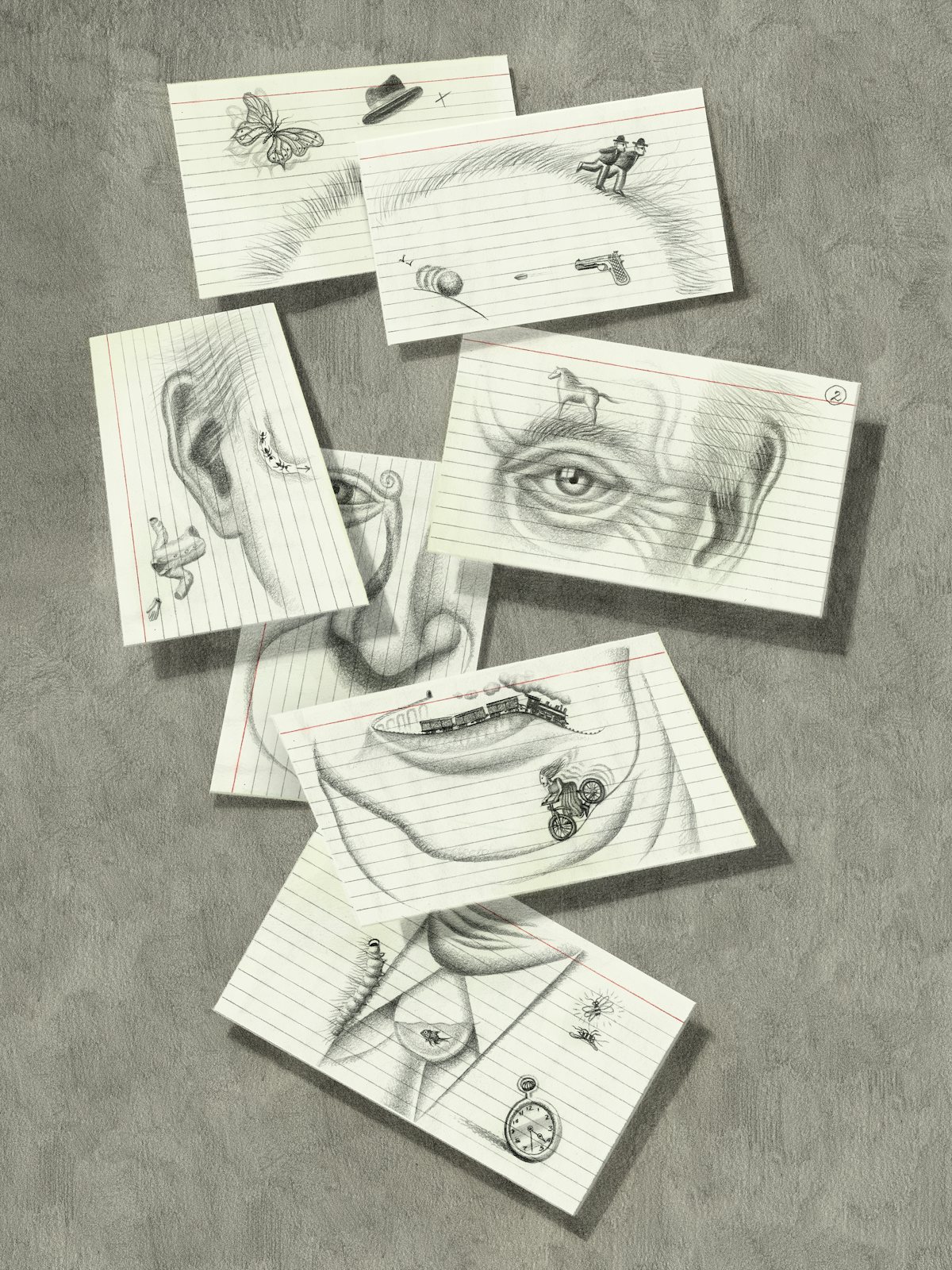

But the heart of Barabtarlo’s book—handsomely designed by Princeton University Press, with a hotel pillow on the cover—is the sequence of three-by-five dream cards from 1964. Nabokov, who was a lifelong and increasingly addicted user of sleeping pills and had a dodgy prostate that forced him to get up a lot (he sometimes noted the times of his nightly bathroom trips, under “WC”), managed even so to dream beautifully of the problems of being an internationally published writer, as in December 1964, while he was checking over the French version of Pale Fire: “On second night here (Hotel Due Torri with large coniferous garden) in doomful half-dream saw the scattered streaks of dim light between the slats of the shutters as a passage which I could not identify translated into French.” The next night brought another doomful image, one which sounds like something in a story by M.R. James: “A tremendous very black larch paradoxically posing as a Christmas tree completely stripped of its toys, tinsel, and lights, appeared in its abstract starkness as the emblem of permanent dissolution.”

The night after that, Nabokov dreams of searching for a pencil with which to grade student papers, while at the same time being disturbed by a “sordid and complicated” affair that he’s had with someone’s wife—whose husband, a small, gesticulative man, is making a noisy scene. “In exasperation I take him and send him flying and spinning into a revolving door where he continues to twist at some distance from the ground.” Is the dream husband dead? “No, he picks himself up and staggers away. We return to the exam papers.” On December 30, Nabokov dreams that he’s dressed in dark pants and a pale green pajama top. A girl dressed in blue rides up on a bicycle. Aha! But Nabokov merely hunts for his socks, while “Soviet delegates pass along the road.”

Vera Nabokov tells her husband her dreams as well, and he notes them down as part of his inventory. In one, she dreams that “big caterpillars, white with black faces, naked, crawl over the furniture.” Early on, Nabokov erroneously believes that he’s found incontestable proof that Dunne’s “reverse memory” thesis is correct. He dreams of a museum, and three days later he watches a film about a museum that seems familiar. He concludes that his dream must have been inspired by a memory of the film before he watched it. Barabtarlo rightly points out that in the dream Nabokov was in fact half-remembering his own short story of years before, “The Visit to the Museum.”

This is a looping, chronologically complicated book full of the kind of sleep-deprived, iridescently edged complexity that likes to gather around Vladimir Nabokov’s work. In the end, all theories of nighttime previsioning are red herrings. Nabokov’s stories and novels and autobiographical essays are the true reverse dreams, where futures pass and interpenetrate, and where the past, like John Dunne’s transparent fishing lures, shines.