David Brooks describes himself as a “proud member” of “the anti-Trump movement” in his latest column for The New York Times, but as the title suggests—“The Decline of Anti-Trumpism”—he’s ashamed of what’s become of the president’s opposition. The anti-Trump movement, he argues, “seems to be getting dumber. It seems to be settling into a smug, fairytale version of reality that filters out discordant information. More anti-Trumpers seem to be telling themselves a ‘Madness of King George’ narrative: Trump is a semiliterate madman surrounded by sycophants who are morally, intellectually and psychologically inferior to people like us.” Brooks contends that while anti-Trumpers obsess over the president’s fitness for office, “the White House is getting more professional” and “briskly pursuing its goals.”

It’s almost as if there are two White Houses. There’s the Potemkin White House, which we tend to focus on: Trump berserk in front of the TV, the lawyers working the Russian investigation and the press operation. Then there is the Invisible White House that you never hear about, which is getting more effective at managing around the distracted boss.

I sometimes wonder if the Invisible White House has learned to use the Potemkin White House to deke us while it changes the country.

David Frum, himself an anti-Trump conservative, implicitly responded to Brooks in a column at The Atlantic, where he warns that anti-Trumpism only seems to be in decline because Americans are becoming numb to the president’s depredations. “We have gotten used as well to the publicly visible consequences of that reality: the lying, the bullying, the boasting,” Frum writes. “We have gotten used, too, to a routine level of disregard for the appearance of corruption: the payments from lobbyists and foreign hotels to Trump-branded properties; the flow of payments to the presidential family from partners in Turkey, the Philippines, India, and the United Arab Emirates; the nondisclosure of the president’s tax returns.”

Frum is much closer to the mark than Brooks; complacent acceptance of Trump’s norm-breaking is a bigger problem than knee-jerk opposition to the president. Yet Brooks does have a point that there are diminishing returns in the singleminded focus on Trump’s personal failings, which reached new heights (or lows) with the publication of Fire and Fury, Michael Wolff’s salacious and questionable insider account of the first year of the Trump White House. Highlighting Trump’s manifest unfitness for office made sense when he was a candidate, but now that he’s president, his personal flaws are only part of a broader, distinctly partisan crisis.

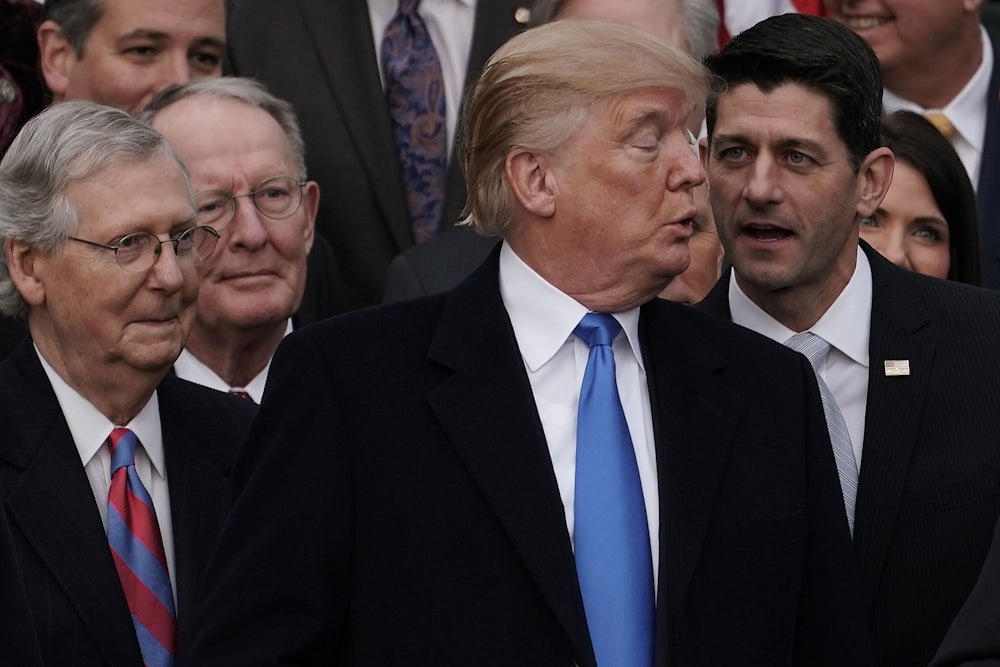

Much of Trump’s power as president is rooted in his support from Republicans in Congress. He and his party are now fused. With the White House becoming “more professional,” as Brooks put it, Trump is acting more like a generic Republican president—pushing tax cuts and an aggressive foreign policy just as much as President Jeb Bush or President Marco Rubio would have. The transformation is somewhat surprising, since Trump ran as candidate unencumbered by party orthodoxy, willing to decry entitlement cuts and criticize George W. Bush for the lies that led to the Iraq War.

But it’s also not a complete transformation. Trump plays the generic Republican awkwardly, as we saw in Tuesday afternoon’s meeting between the president and Congress. When House Minority leader Nancy Pelosi argued for a clean bill to fix Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, Trump was eager to go along with the idea. He had to be reminded by Republican Congressman Kevin McCarthy that the GOP was against a clean DACA bill:

Here's the incredible moment where Trump initially agrees to Feinstein's suggestion that they do a clean DACA bill, before being corrected by Republicans about what she was actually suggesting. pic.twitter.com/RaXAQAi8JF

— David Mack (@davidmackau) January 9, 2018

It’s unclear that Trump even understands that a “clean DACA bill” means legislation that has no other issues attached to it. During the meeting, Trump said:

TRUMP, word for word: "I think a clean DACA bill, to me, is a DACA bill, but we take care of the 800,000 people ... but I think, to me, a clean bill is a bill of DACA, we take care of them, and we also take care of security."

— Ryan Struyk (@ryanstruyk) January 9, 2018

In deciding to govern as a mainstream Republican, Trump has received not just the support of the Republican Party, but its protection from congressional investigation. As Frum wrote, “We have gotten used to the president’s party in Congress sabotaging and discrediting the investigation into foreign manipulation of the U.S. presidential election.” Trump and the Republican Party have a de facto bargain: He gives party leaders control over the agenda, and they tolerate and defend him from accusations of corruption and collusion with Russia.

Leading up the 2016 election, it was possible to imagine a broad anti-Trump coalition that included conservative Republicans like Brooks. But after the chaos wrought by Trump’s candidacy and victory, American politics is again sorting itself along usual partisan lines. If Trump’s personality cult has merged with the Republican Party, then the only effective anti-Trump movement will be among partisan Democrats, who vote not just to stop the president but also the party that enable him. There are plenty of signs, based on the healthy number of candidates running, that the anti-Trump resistance is now focused on defeating the Republicans in this year’s midterm elections.

Brooks is extremely vague about the parameters of “anti-Trumpism,” which he never defines, thus eliding the differences between conservative and liberal opposition to the president. Now that the GOP has acquiesced to Trump, the anti-Trump Republicans who emerged in the run-up to the 2016 election, like Brooks and Frum, are political orphans. In “The Decline of anti-Trumpism,” Brooks is really just mourning the decline of his particular brand of it.