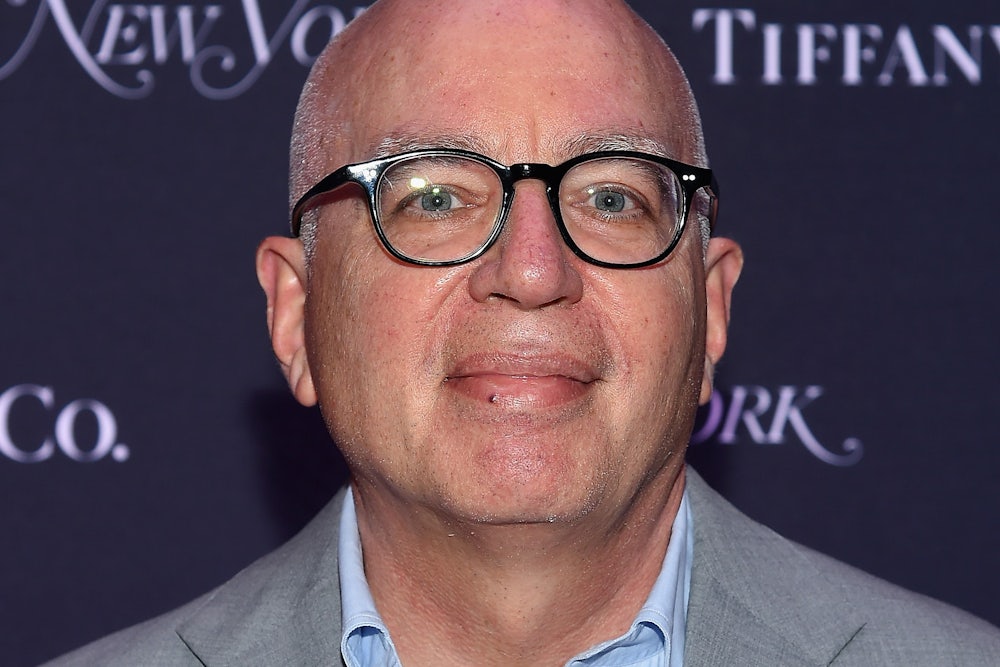

Fire and Fury, Michael Wolff’s forthcoming account of the first year of the Trump administration, has everything we have grown to expect from a Michael Wolff joint: snappy dialogue, juicy morsels revealing what some of the most powerful people on earth really think, and a pervasive unscrupulousness. Fire and Fury is a magpie’s nest built out of gossip Wolff traded with Donald Trump’s inner circle. Thus we learn, from excerpts in New York, The Guardian, and The Hollywood Reporter, that Steve Bannon described Donald Trump Jr.’s 2016 meeting with Russians at Trump Tower as “treasonous.” We learn that Trump told the White House staff not to pick up his shirts off the floor, that Trump is so out of touch that he did not know who John Boehner was, that Trump’s famous hair covers “an absolutely clean pate—a contained island after scalp-reduction surgery.”

What ties all of this gossipy ephemera together is a central thesis: that Trump is singularly unqualified to be president, and everyone around him knows it. It’s a classic story: The emperor has no clothes. The problem is that we already knew this from less salacious reporting extending back years. Wolff’s main contribution to what we know about Trump is a willingness to seemingly say anything, whether or not it’s strictly true—and that only bolsters the Trump administration’s case that the fake news media is out to get him.

This insouciant relationship with the truth is just as central to Wolff’s work as his commitment to access and gossip. Writing in The New Republic in 2004, Michelle Cottle skewered Wolff for proudly disregarding accuracy:

Much to the annoyance of Wolff’s critics, the scenes in his columns aren’t recreated so much as created—springing from Wolff’s imagination rather than from actual knowledge of events. Even Wolff acknowledges that conventional reporting isn’t his bag. Rather, he absorbs the atmosphere and gossip swirling around him at cocktail parties, on the street, and especially during those long lunches at Michael’s.... “His great gift is the appearance of intimate access,” says an editor who has worked with Wolff. “He is adroit at making the reader think that he has spent hours and days with his subject, when in fact he may have spent no time at all.”

Wolff has pushed back against this characterization, telling Axios that he has tapes that back up private (and seemingly dubious) conversations between Bannon and former Fox News chief Roger Ailes. But already Wolff has been caught making very suspicious claims. The claim that Trump didn’t know who John Boehner was, relayed with relish in Fire and Fury, is meant to illustrate Trump’s basic policy illiteracy: This guy is so clueless he doesn’t even know who the last speaker of the House is! The problem, however, is that Trump obviously knows John Boehner. The two went golfing together, and Trump repeatedly mentioned Boehner on the campaign trail and in his tweets.

There’s more. Did the billionaire Robert Mercer give $5 million to Trump’s campaign? Campaign finance laws would bar such a contribution. Did Rupert Murdoch really call Trump a “fucking idiot”? Who knows. Are Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner plotting Ivanka’s presidential run? We’ll see.

Wolff has attempted to gloss over these inaccuracies, falsehoods, and unverifiable claims with a kind of postmodern poetic license, arguing that they all point to the big, central truth of his project. In an introduction to the book, Wolff writes:

Many of the accounts of what has happened in the Trump White House are in conflict with one another; many, in Trumpian fashion, are baldly untrue. Those conflicts, and that looseness with the truth, if not with reality itself, are an elemental thread of the book. Sometimes I have let the players offer their versions, in turn allowing the reader to judge them. In other instances I have, through a consistency in accounts and through sources I have come to trust, settled on a version of events I believe to be true.

This bordering-on-fabulism tendency may reflect the messiness of reality in the Trump era, but it has also driven much of the justified criticism of Fire and Fury. The White House, the Republican National Committee, and a number of journalists have used it as a cudgel over the past day. And they may be understating the problem with Wolff’s reporting in Fire and Fury.

Because the entire news media is structured on “new news”—novel reporting that is then chewed over by talking heads for hours—Wolff has been booked everywhere from TODAY to Meet the Press to discuss his scoops. But while many of Wolff’s details are new, his broader point is familiar to anyone who has spent the past year reading The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time, The Atlantic, and The Daily Beast, or watching those same cable news shows. The story that Wolff relates in Fire and Fury is the story of the Trump administration writ large: Trump is an unstable, angry, and incompetent man who is fundamentally incapable of governing. Stories of Trump locking himself in his room, raging at aides, and watching hours of cable television have become common knowledge.

There is value in publishing a larger, contextualized account of the Trump White House. There is nothing to be gained, however, from reporting information about Trump that can’t be locked down. Wolff’s recklessness fuels the Trump administration’s critique of journalists and the media. It suggests that journalists really are out to get the president—after all, in Fire and Fury, Wolff suggests that journalists will print anything, so long as it casts Trump in a bad light. The rewards are clear: His cavalier reporting has led to TV bookings, a #1 Amazon bestseller, and insane traffic for any of the outlets that agreed to publish his work.

Wolff’s main claims—that the Trump campaign didn’t expect to win, that they were unprepared to take the reins of power, that Trump himself is unfit for office, and that his advisers are powerless to control him—all track with reality. But Wolff’s seeming inability to distinguish between fact and fiction, between fluffy gossip and valuable information, ultimately undercuts his work. And ours, too.