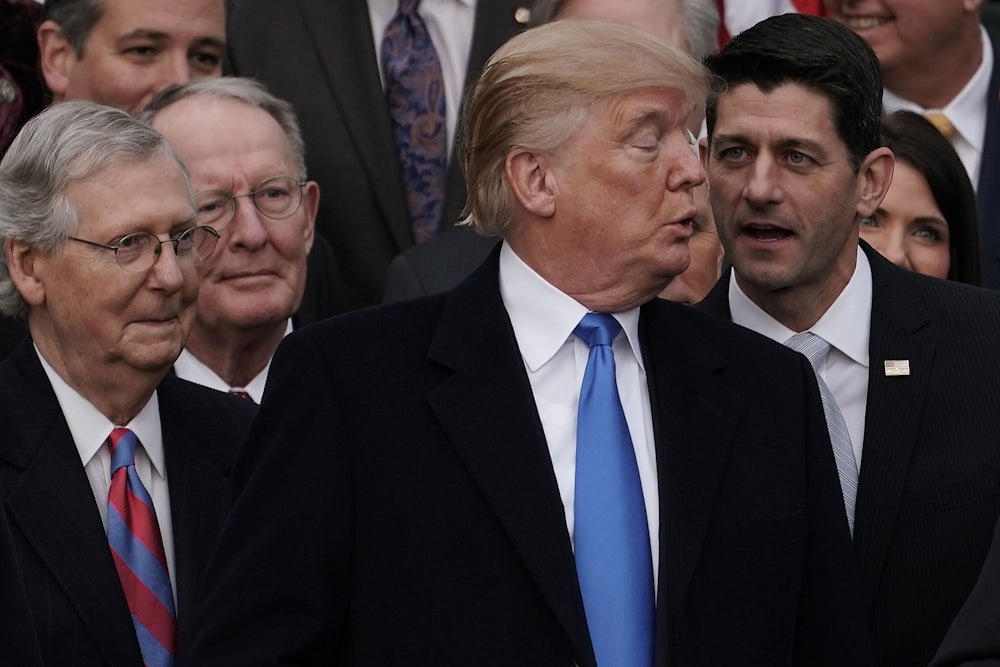

Want to enrage liberals? Tell them that Republicans are about to take away federal food assistance from more than 40 million poor Americans, mostly children and the elderly. Over the Christmas holiday, two Twitter users did just that, claiming that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan were on the verge of eliminating the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), otherwise known as food stamps.

Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan both agreed today on Fox news that the food stamp program needs to come to an end

— Allen Marshall (@AllenCMarshall) December 24, 2017

Marshall only has a few thousand followers, but three days later, Ed Krassenstein, a self-described “entrepreneur, journalist, bitcoin & stock investor” with more than 600,000 followers, repeated Marshall’s claim.

Today on @FoxNews @SenateMajLdr and @SpeakerRyan agreed that the food stamp program needs to be ended.

— Ed Krassenstein (@EdKrassen) December 27, 2017

So not only does this GOP, who gives huge tax breaks to the wealth, want to take healthcare from poor, sick children, but they want to take food from these kids as well.

Thousands of people replied to the tweets. Some told personal stories about how SNAP pulled them out of poverty, while others decried the “unspeakable evil” of the Republican Party.

We have the adult version of "Children of the Corn" in the WH and Congress. Its like they're on a mission to eliminate our most vulnerable citizens (elderly and children from low income households). Despicable.

— Annette Evans (@evannablue) December 29, 2017

Alas, these tweets were Fake News. Neither McConnell nor Ryan were interviewed on Fox News or Fox Business that day, nor were the words “food stamps” or “SNAP” uttered by any hosts or guests, according to a review of Fox News’s December 24 programming. In fact, neither Ryan nor McConnell have ever said that they want to completely end SNAP, the entitlement program that in 2016 provided $73 billion in food assistance to low-income households. Nor did either men release specific proposals to reform the program in 2017.

But it’s understandable why liberals might be sensitive to the possibility of such cuts. The Republican-controlled Congress tried in 2017 to take away health insurance from 13 million people, and successfully passed a tax bill that redistributes wealth from from the poor to the rich. Now, Ryan’s next priority appears to be entitlement reform. “We have to address entitlements, otherwise we can’t really get a handle on our future debt,” he said recently on CBS This Morning. “We, right now, are trapping people in poverty. And it’s basically trapping people on welfare programs, which prevents them from hitting their potential and getting them in the workforce.”

Welfare policy analysts and SNAP advocates tell The New Republic they expect to see changes to the anti-hunger program this year. There are several opportunities to do so. There’s entitlement reform, but also the farm bill, which funds SNAP and is up for reconsideration in 2018. Republicans could also push SNAP reforms through the budget reconciliation process. Whatever process they choose, “[Republicans] are going to want to do some things with SNAP, there’s no question about it,” said Robert Doar, a poverty studies fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “Some people are going to say they’re awful things. But I think their real intention is to help people work so they can increase their income and need less SNAP benefits as a result.”

While it’s impossible to know what those reforms will entail, there are a number of likely options. If the approach is anything like what the Trump administration has proposed, billions would be drained from the safety net program. If it’s what Ryan has advocated in the past, it would be a structural change that would render SNAP a shadow of its current self. And if it’s what Republicans on the House Agricultural Committee seem to want, it’ll be incremental changes that affect what kind of food people can buy and how hard they have to work to get it. Any of these paths will guarantee an election-year showdown over how America should treat its neediest citizens.

Neither Mitch McConnell nor Paul Ryan like SNAP the way it is. In 2013, McConnell voted against a Senate-proposed farm bill because he believed the SNAP program was too generous and that it should have work requirements. “Why would anybody object, if they can be given employment, to being productive?” McConnell said. “We need to move in the direction of having a vibrant, productive, expanding economy. And you don’t do that by making it excessively easy to be non-productive.” Two years later, he said business leaders have told him they have “a hard time finding people to do the work because they’re doing too good with food stamps, Social Security and all the rest.”

Ryan’s complaint is that SNAP is automatically funded every year, with the amount dictated by need (however many people qualify for the program in a given year). So Ryan has championed turning the now-flexible entitlement into a block-grant program containing a strict amount of funds for each state, with the terms of those funds dictated by the state. His infamous “Opportunity Grant” proposal in 2014 was to consolidate 11 programs, including SNAP, into a single block grant. His “Better Way” program in 2016—alongside House Agriculture Committee Chairman Mike Conaway—also sought to block-grant the program.

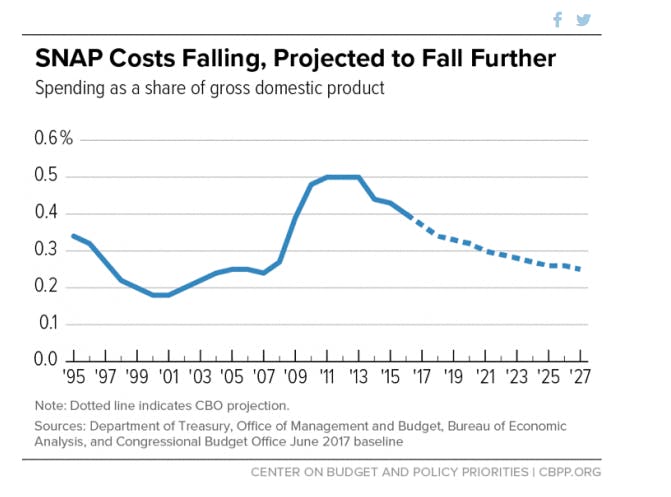

Ryan’s argument is that the entitlement structure encourages dependence and abuse. “Spending on SNAP has quadrupled in the past decade,” his staff explained in 2014. “It’s grown in good times and bad, because of the open-ended nature of the program. States get more money if they enroll more people. This setup encourages waste, fraud, and abuse.” But as the progressive think tank Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) points out, SNAP spending increased because of the Great Recession—and since then has been steadily declining as a share of the economy. In fact, Congressional Budget Office projections show that SNAP spending as a share of the GDP will return to 1995 levels by next year.

CBPP argues that Ryan’s proposal would essentially end SNAP as we know it. “Converting SNAP to a block grant would rob it of its most important structural feature: the guarantee it provides across the country to help low-income households afford an adequate diet,” Dottie Rosenbaum, a CBPP senior fellow, wrote in March. States could also make eligibility requirements more strict, or decrease the amount of money they give to individual families. Opponents also argue that SNAP is already working well, so there’s no reason to change the structure so drastically. “[Block-granting] would be a horrific undermining of the safety net that currently has made a huge dent in food insecurity,” said Ellen Vollinger, the legal director of the Food Research and Action Center, a nutrition advocacy group.

Still, it’s feasible that block-granting SNAP could be on the table this year, either within entitlement reform or the farm bill. Ron Haskins, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former welfare policy advisor to President George W. Bush, speculated that SNAP could be an area of compromise between reform-hungry Ryan and McConnell, who, in this election year, is reportedly reluctant to go after large, popular programs like Medicaid and Social Security. “If they were going to hit a welfare program, they’d be especially likely to hit food stamps,” Haskins said.

President Donald Trump is also a proponent of block-granting SNAP. The proposed budget he released in May not only proposed slashing $193 billion—a 25 percent cut—over the next 10 years, it also sought to trim $150 billion from SNAP through “block grant-type structural changes” toward the end of that 10-year window. The Trump administration also proposed having states pay for 25 percent of the food stamp program. The federal government currently funds the entire cost of benefits.

The House budget committee, however, appears to recognize the controversial nature of these proposals. When asked in July if SNAP would be block-granted, Rick May, staff director of House Budget Committee, said, “We’re not necessarily using the phraseology of block grants.” And the House Agricultural Committee—which has the most power over the farm bill—held 16 hearings on SNAP from 2014 to 2016, with more than 60 witnesses, and produced a report that specifically advocated against major reform. “You will find nothing in this report that suggests gutting SNAP or getting rid of a program that does so much to serve so many,” the committee’s Republican leaders said in a statement at the time.

This is why some analysts are skeptical that Congress will gut SNAP in 2018. “My prediction ... is that they’re going to end up working SNAP reform through the farm bill, and it will be a list of 8 or 10 things that are pretty in the weeds,” said Doar, of the American Enterprise Institute. Most likely, he said, Republicans would seek stricter work requirements—SNAP currently requires adult recipients without dependents or disabilities to work 20 hours per week—or add a provision requiring recipients to only buy healthy food. The Trump administration supports these ideas, too. Progressives counter that most beneficiaries are already employed, and that many poor people live in food deserts where healthy food options aren’t readily available.

Whatever path Republicans choose won’t be easy. While the House has the votes to pass large cuts to SNAP, Senate Republicans only have a one-vote majority; several of its moderate members, like Maine’s Susan Collins, or those facing a tough reelection fight in a purple state, like Nevada’s Dean Heller, might balk at cutting programs for the needy. Still, Ryan is pushing Trump to declare entitlement reform his next policy priority. If that happens—and food stamps are on the chopping block—there will be a much louder reaction than a few thousand replies to a pair of fake tweets.

Correction: Due to an editing error, this article misidentified the state that Senator Dean Heller represents.