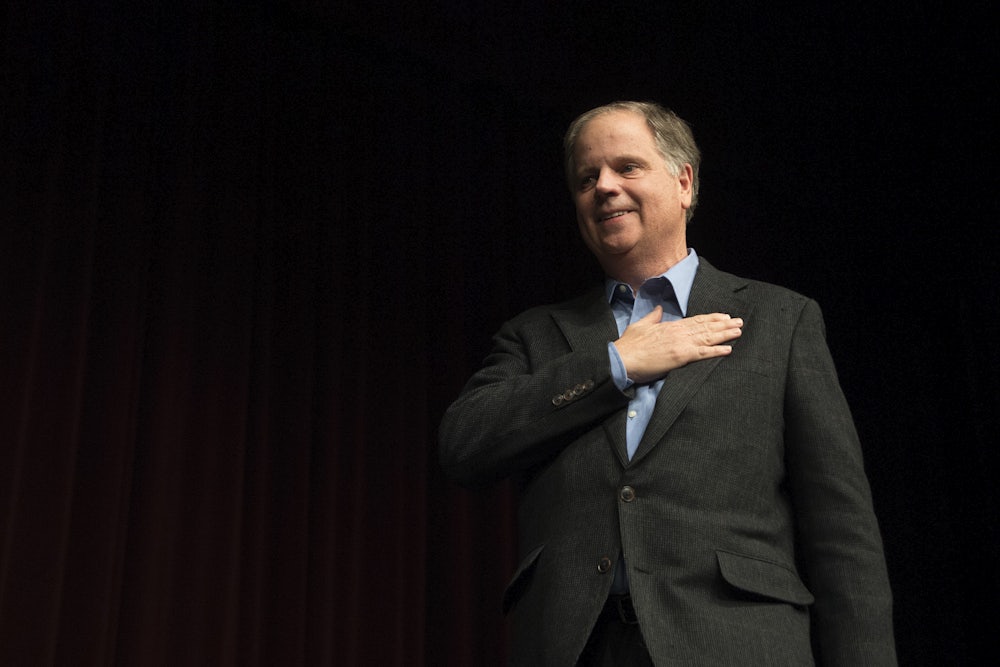

Is the honeymoon already over? Democrats who were basking in the afterglow of wins in Virginia and Alabama got the jitters over the weekend when the victorious candidates—Governor-elect Ralph Northam and Senator-elect Doug Jones, respectively—both sounded a moderate note. The Washington Post reported that Northam could try to leverage his landslide win by plucking “a few Republicans out of the General Assembly—where the GOP is holding onto the majority by a thread—and give them jobs in his Cabinet to tilt the balance of power toward Democrats. He could try to ram through a broad expansion of Medicaid and other Democratic priorities. But Northam says he is not looking to vanquish the other side.” Meanwhile, Doug Jones told Fox and Friends on Sunday that he was not automatically opposed to the Republican tax bill, saying, “We’ll wait and see how it goes.” On Monday, Jones told CNN that Trump shouldn’t resign over sexual assault allegations.

For the Democrats who raised money, canvassed, and voted for Northam and Jones, it was surely disheartening that the men turned so mealy-mouthed even before taking the oath of office. Of the two, Jones’s centrist tone is the more defensible. Alabama is an extremely conservative state, and he won a narrow victory against an accused child molester. It’s easy to understand why Jones would want to placate right-wing Alabama voters. Northam, on the other hand, won by 9 percentage points in a state that his been trending blue for more than a decade. Pushback from liberals on Northam’s Post interview compelled his staff to tweet messages explaining his Medicaid position:

That is why today my budget will expand Medicaid for the Commonwealth of Virginia.

— Terry McAuliffe (@TerryMcAuliffe) December 18, 2017

And as he has said repeatedly, @RalphNortham will fight for this as the next #VAGov https://t.co/m0N6o82AaW

— Ofirah Yheskel (@ofirahy) December 18, 2017

Northam and Jones are hugging the center at the exact moment when the Republican Party is itself going to extremes by jamming through a plutocratic tax bill and by orchestrating a campaign to defame special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of the ties between Russia and the Trump campaign. The two parties are following a pattern of asymmetric polarization familiar since the early 1990s. The Republicans are moving further right, and are ever more willing to violate longstanding norms, while the Democrats position themselves as a conciliatory party open to bipartisanship. The paradox of the Trump era is that the party that controls all three branches of government is deeply inimical to the democratic system while the party that believes in governance is shut out of power.

But perhaps it is precisely because Democrats have so little foothold in power that they are forced to be more propitiative. In their current exile from power, Democrats need to win over more voters, including many who voted Republican in recent years. And the party thinks it know where to find them: the suburbs. But will this tropism toward the center have the negative side effect of alienating the newly energized Democratic base?

Democratic centrism isn’t just a matter of ideology, but is also motivated by political strategy, particularly the belief among Democratic political consultants that the path to victory runs through traditionally Republican suburbs. As The New York Times noted on Monday, “from Texas to Illinois, Kansas to Kentucky, there are Republican districts filled with college-educated, affluent voters who appear to be abandoning their usually conservative leanings and newly invigorated Democrats, some of them nonwhite, who are eager to use the midterms to take out their anger on Mr. Trump.” Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel subscribes to this theory, telling the Times, “If you look at the patterns of where gains are being made and who is creating the foundation for those gains, it’s the same: An energized Democratic base is linking arms with disaffected suburban voters.”

There’s one very compelling reason to be wary of this pursuit of disaffected suburban Republicans: Hillary Clinton tried it last year. As New York Senator Chuck Schumer described the strategy in July 0f 2016, “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.” While Clinton performed well in prosperous suburbs, this didn’t offset her losses with working-class whites, which led her, contra Schumer’s prediction, to lose Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Wisconsin, among other previously Democratic states. Clinton ended up winning fewer Electoral College votes than any Democratic candidate since Michael Dukakis.

The Democratic Party’s fetishization of the suburban voter has myriad roots. These are desirable voters, in theory, because they are more likely to vote in midterms than more traditional Democratic constituencies like the young, the poor, and people of color; they’re also more likely to be substantial donors. And for Democratic centrists, middle-of-the-road Republicans are also ideal voters since they are unlikely to demand large government programs.

The Democrats have pursued suburban Republican voters since long before 2016, to little avail. “Democrats have dreamed for years of peeling away the rings around major cities, separating suburban voters who favor conservative tax and economic policies from a Republican Party that also champions harder-right positions on abortion, guns and gay rights,” the Times reported. “So far, that effort has gained Democrats few seats.” The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee reportedly found that in the 2014 and 2016 elections, suburban voters were “inching away from Republicans, but too slowly to flip many seats.”

But some argue that Donald Trump’s presidency will accelerate that trend. Trump, the theory goes, is so deeply loathed by college-educated suburbanites that many are ready to flip parties. Some analysts credit suburban disillusioned Republicans as being pivotal in the victories of Northam and Jones. As Times poll-watcher Nate Cohn tweeted:

I think it's interesting that the big Alabama turnout surge happened in well-educated areas, even though in AL well-educated areas are often very conservative pic.twitter.com/05f44ot7zx

— Nate Cohn (@Nate_Cohn) December 18, 2017

But Cohn’s rival data-cruncher Nate Silver, of FiveThirtyEight, argues the evidence is much more ambiguous:

Small sample, but if you look at special election results so far, Democrats seem to have improved the most relative to 2012/16 baselines in the *least* suburban states/districts. (data via @ForecasterEnten) pic.twitter.com/XtMeJV9yD2

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) December 18, 2017

Not necessarily. In terms of vote share, Northam's biggest gains relative to Clinton were in red, rural counties, especially in Southwest Virginia. Turnout was up more in blue-ish, suburban counties, though. https://t.co/60wg77ZJFY

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) December 18, 2017

One crucial point that Silver makes clear is that Trump’s unpopularity gives Democrats a chance to activate all sorts of voters, not just the suburban Republicans. The victories were driven more by the strong enthusiasm of the base as by converts from the GOP. And some of those former Republicans aren’t affluent or college-educated, but working class and rural.

Lasting electoral victories won’t be won just by chipping off a discrete group from the Republicans. It’s much more important for Democrats to create a coherent coalition that shares the same values.

Northam and Jones both won by running as unabashed liberals in the context of their own states. They are uncompromising supporters of reproductive freedom and LGBT rights. Northam campaigned on a promise to raise the minimum wage to $15, while Jones spoke out on behalf of the Affordable Care Act. Given the mixed nature of their support, they have to use enough bipartisan language to keep new Republican converts on board, but not sacrifice policy concerns, like defending and expanding the social safety net, that the base cares deeply about.

Suburban ex-Republicans are worth pursuing, but not at the risk of diluting liberal policy commitments. While opposition to Trump is helping to swell Democratic ranks, the truth remains that excessive centrism will dishearten core voters. Watering down the party’s identity only ensures more defeats further down the road, when Trump won’t be around to scare up an ad hoc Democratic coalition. “Virginians deserve civility,” Northam told the Post. “They’re looking for a moral compass right now.” But Democrats don’t need Republicans to help calibrate that compass.