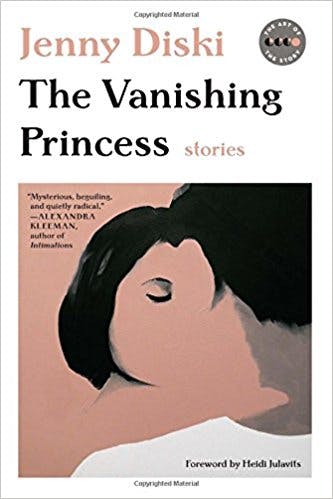

The Vanishing Princess is

Jenny Diski’s only collection of short stories, recently published for the

first time in the U.S. (it came out in the U.K. in 1995). In her introduction to

the book, Heidi Julavits calls it “an

artist’s sketchbook” for Diski, who, before her death in 2016, was better known for her ten novels, eight works of nonfiction, and reams of criticism for The London Review of Books. She seemed to always have been there, a ubiquitous voice that, as this collection shows, turns out to have been irreplaceable.

The Vanishing Princess finds Diski in reflective mode. The first story is about the eponymous princess, but its subtitle—“Or, The Origin of Cubism”—suggests something more than a modern fairytale. Once upon a time, a princess lived in a tower all alone. A soldier arrived and brought her food, which he liked to watch her eat. Then a second soldier came, and gave her other things she hungered for: a mirror and a calendar. Her appearance distressed her at first. The second soldier stood next to her, and “she watched his reflection standing next to hers and telling her, ‘That is you.’”

The first soldier came back. Seeing that another man had brought a mirror, he “took off a diamond ring he wore and … etched the outline of the princess’s reflection on to the glass.” When the second soldier returned, he made the princess stand before the mirror so that her reflection precisely filled out the first soldier’s outline. Then he, too, took off a diamond ring, and with its edge “drew around the reflection of her eyes,” then “filled in the lids, the pupils and the irises.” Now, within the outline, “a pair of eyes stared out.” They were “fixed in an expression of longing and alarm so poignant that the princess gasped. She could no longer see her own eyes when she looked in the mirror.”

The first soldier became more interested in looking at the eyes in the glass than watching the princess eat. “Now, on each visit, the soldiers added to the portrait in the mirror.” The princess’s original reflection “became no more than a frame, as each man added a feature according to his mood. An elbow was matched with the bridge of a nose; a wrist with a knee; a buttock curved beside an anklebone; one ear rested on a fingernail.” Finally, she couldn’t see herself at all. She disappeared.

In presenting a fairytale about three-dimensional representation, Diski focuses not on the person doing the looking, but the person being looked at. It is a story about being, not about seeing. Like almost every story in The Vanishing Princess—which, as Julavits puts it, are all bound together by “their feministly interrogative nature”—the tale takes up one aspect of feminine experience and inflates it into a beautiful and monstrous parable.

Let’s take Cubism as a cipher for the creative projects of men. Those projects’ origins, Diski says, belong less with real women than with their reflections, which are then elaborated into representational practices through games of careless tennis between communities of men. The original subjects of those works end up obscured even from themselves. As representation of the world takes on multiple dimensions in men’s hands, the level at which women can see themselves truthfully reflected is lost.

In retelling folk stories with new female perspectives, The Vanishing Princess’s closest ally is Angela Carter. Like Carter, Diski presents women who are living inside roles. She gives us the internal monologue of the gazed-upon woman. Some retellings are simply funny and sexy, like “Shit and Gold,” which reimagines Rumpelstiltskin. Rather than having to discover the imp’s name, the miller’s daughter becomes the queen by making him forget it. And she enjoys doing it.

In “Bath Time,” a woman gives up everything in her life for the single perfect experience: a bath. She invests every penny she has in a pristine white tiled room containing practically nothing but a white towel, a black bottle of bath oil, a sink. We never get to experience the bath itself, but at the story’s end we share with her the delicious bedtime of a woman who knows that the next day will be the greatest of her life. The principal idea here is of fulfilling desire, to the detriment of everything else in the universe, because it is all that matters.

Desire is found in other stories. “Housewife” is a deliciously lascivious story about the sexual connection between a housewife and her lover. Their correspondence is ridiculously florid, and Diski does a beautiful juggling act of celebrating a woman coming into new sexual consciousness while showing how silly and sweet human beings are when they’re doing that kind of thing. Her focus remains on the experience of the reflected self: “Filled with desire at her image and lusting dreamily for herself,” Diski writes of her heroine, “she watched her reflection slide her fingertips lightly down her body, from shoulder to breast, pausing to cup it softly and squeezing the nipple between thumb and finger.” Her “saturated labia” are “as silky and smooth as the satin covering her breasts, as slippery and wet as the liver she had donated to the cats.”

If many stories in The Vanishing Princess are about tapping into the hidden desire at the heart of the self, others are about its destruction by an outrageous world. The very minimal concept story “Short Circuit” describes a woman driven mad by her conviction that her partner is not telling her the truth about not telling her the truth. “Wide Blue Yonder” gives us a dissatisfied woman who makes the sudden and exciting leap into the “perfect pleasure” of drifting out to sea, away from her bad husband, towards her certain death.

For all the affirmation of female interiority in these stories, therefore, Diski also gives us a low hum of dread and perturbation. There’s a distant wryness to the narrative voice of The Vanishing Princess, one which uses fairytale cutouts to make everyday life seem both ridiculous and frightening. Madness and evil are as omnipresent as they are in fairytales, and they hide just out of our sight—only one thwarted desire, one misunderstanding away—in our own heads.