In Isfahan we ate sour cherries and raw tamarind in the schoolyard. We went on picnics in the mountains, pots of basmati rice strapped to my parents’ backs. People fell in and out of love, made music and poetry, as they have always done. Iran was only a few years past the revolution, and somehow, even as a child, I sensed that I had been born in an unlucky chapter of its history.

In the 1980s, we still hoped for another regime change, a disruption of the theocracy’s stifling rules. Another revolution would surely come. Slowly that fantasy faded. Men and women learned to seek pleasure in secret. They drank and smoked and listened to illegal music. One night at a party, I saw a woman strip off her clothes as she danced. The other women removed their headscarves but kept them within reach. Before leaving, they draped themselves in black again.

I’ve often tried to imagine my life if my family hadn’t escaped in 1987, when I was eight years old. Young Iranians now understand that another revolution may not come in their lifetimes (though I’m learning never to underestimate my fellow Iranians). As we speak, they’re rising up again for their freedoms. But until now, women have learned to carve out a life for themselves inside the hijab. They haven’t vanished. They wear the clothes hidden in their closets. They study science and math. They ski and swim fully covered, dye their hair pink, tweet, dance, have sex, meet in coffeehouses for pastries or to study for exams. They live well.

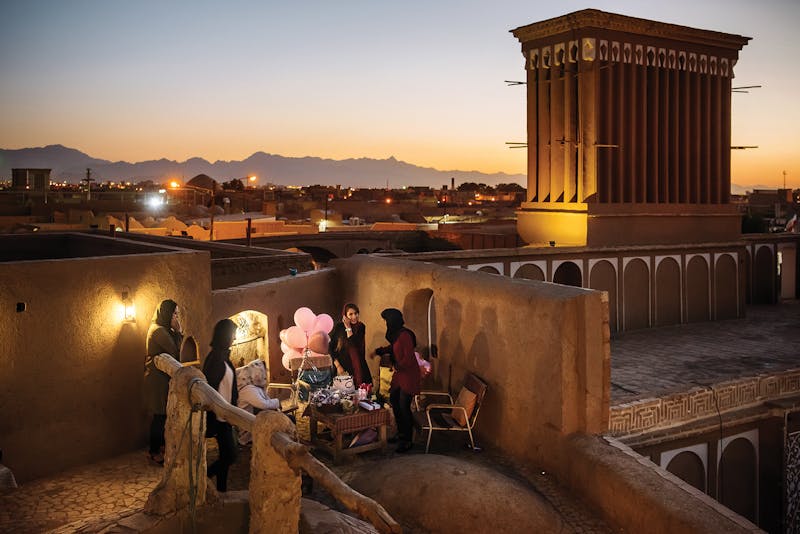

But secrets emerge from the mundane, markers of human need and imagination: mothers done up to go to the new Western supermarket, an inch of bottle blonde begging to be noticed; pink balloons lighting a lone rooftop at night. A woman in tight jeans passes under the gaze of a ghoulish Lady Liberty, while another, wrapped from head to toe on a hot day, watches half-naked boys swim. It is maddening and illogical and unfair: a wound inside every photo.

When I look at these Iranian women, with their scarves pushed dangerously back, I think of my mother, who was stopped by the morality police on the streets of Isfahan for a few loose strands. I think of the time her hijab slipped as she was rescuing my two-year-old brother when he wandered into traffic, and how the men screamed insults at her; how afterward her cheeks glistened with rage. It takes bravery to be a woman in Iran. Just leaving the house is a small act of subversion. And yet when I first looked at these images, I wasn’t outraged or even sad. I remembered my childhood, the tang of sour cherries in my mouth—how richly we lived on these small pleasures. It was a kind of rebellion, to seek joy, to laugh and play, to be seen when the law prefers you erased.

A woman in a hijab walks past the graffitied wall of the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran, where Iranian students took 66 Americans hostage in 1979. Women were some of the strongest supporters of the Islamic Revolution, which they believed would deliver equality between the sexes.

Children play in a fountain in Isfahan, watched by a woman in a chador. For much of the twentieth century, black chadors were only worn for mourning or by ultrareligious women, until 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini dubbed them “the flag of the revolution.” Today, all women must cover their heads in public.

Worshippers rest at a mosque in Kashan. Roughly 90 percent of Iran’s population is Shiite, and although sharia law is the foundation of the country’s constitution, women are still able to hold jobs in the national parliament and on local government councils.

In Maymand, an ancient village south of Tehran, life—and gender roles— remains much as it has for centuries. These women and their families live in caves dug into the rock, while the men earn a living as nomadic shepherds.

A woman photographs her son during a visit to the ruins at Persepolis. After the revolution, Iran’s ruling clerics rolled back the Shah’s 1967 and 1975 family protection laws, which raised the minimum age at which women could legally be married and allowed them to petition for custody of their children.

Women learn to drive at a school in Yazd. Unlike in Saudi Arabia, which only recently lifted its ban on women drivers, Iranian women have maintained their freedom of movement even after the revolution— a liberty and a necessity, as women make up 18 percent of the workforce.

Customers shop at the Hyperstar in Isfahan, Iran’s first international supermarket chain. Foreign investment, allowed by the current moderate government, has given the country’s traditional women a glimpse of global consumerism.

Women gather for a party on a roof in Yazd. Under sharia law the consumption of alcohol is punishable by public lashing and, for repeat offenders, a mandatory death sentence. Yet Iran’s major cities still have a vibrant nightlife: It is simply enjoyed, by both men and women, in private.

This essay originally appeared in the Jan/Feb issue of The New Republic. It has been updated to reflect recent news events.