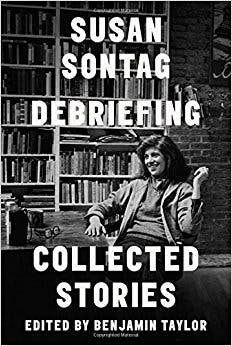

The last collection of Susan Sontag’s short fiction was published in 1977, under the title I, etcetera. Now a new volume called Debriefing is coming out, which collects the eight stories from I, etcetera along with three more: “Pilgrimage,” “The Letter Scene,” and her most admired story, “The Way We Live Now,” first published in 1986. Sontag’s fiction is a smaller oeuvre than her nonfiction, which has taken on such an inflated role in the culture that it is difficult to see around it. Meanwhile, Sontag the personality has grown so large in death that it threatens to eclipse her work: She is remembered as a narcissist, a pugilist, the enemy of Camille Paglia, and a genius. This new collection may not offer anything strictly new, but it does allow us examine a side of Sontag that is often obscured by those two pillars of her legacy.

Although Sontag never stuck to one line of thinking for long (The New Yorker’s obituary noted that, “as she saw it, she was entitled to frame bold opinions, and to change them as the world changed”), she defined American twentieth-century thought as much as Foucault or McLuhan. Notes on Camp (1964), Against Interpretation (1966), and On Photography (1977) are great and generous contributions to the project of criticism. Sontag wrote about politics and illness and mass media, and she did it properly.

Recall that line in On Photography about why great industrial nations (Germany, Japan, America) produce tourists who take photographs while on holiday: “Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they take pictures.” This is a tiny encapsulation of the best of Sontag: authoritative but unexpected and playful. She is not quite judgmental, but takes our temperature as though she is the pediatrician and we are the child.

Paglia’s two most famous put-downs capture the contradictory nature of anti-Sontagism. Sontag is “synonymous with a shallow kind of hip posturing,” Paglia wrote, but also she is a “sanctimonious moralist of the old-guard literary world.” These two epithets don’t blend easily, but if we force them together it makes a kind of sense: Paglia sees in Sontag a deep shallowness, a newfangled old-timeyness, a moralizing hipster. It’s the figure that prompted the writer Kathy Acker to quip, “Dear Susan Sontag, Would you please read my books and make me famous?”

Sontag’s short fiction is a rebuke to this stereotype. Not all of it is excellent, but it is all stylish. “Project for a Trip to China” is a list of aphoristic assertions about China—where the narrator has never been—that are more about the imagination than a real place. The piece is an investigation into Orientalist desire that takes apart its components, but does nothing more: “Myrna Loy China, Turandot China. Beautiful, millionaire Soong sisters from Wellesley and Wesleyan & their husbands. A landscape of jade, teak, bamboo, fried dog.”

Here, Sontag’s form invites the reader to understand desire as a patchy list of fragments that do not cohere, even on a sentence level. “I am interested in wisdom. I am interested in walls. China famous for both.” She presents a desire in detail, but it is an uninterrogated desire. This renders the form of the story interesting but its substance sludgy and disappointing. It is a basket of bad ideas laid out beautifully.

In “Pilgrimage,” the first person narrator (who seems very much like Sontag herself) recalls meeting Thomas Mann against her will as an adolescent. Her best friend Merrill has found him in the telephone book and obtained an invitation for Sunday tea. The narrator is deeply embarrassed by the occasion, which brings her favorite old-world writer slap bang into her dreary Californian life. She makes it through the ordeal—“…I remember I thought his mustache (I didn’t know anyone with a mustache) looked like a little hat over his mouth”—but hates every moment.

It’s a weird little story, structured more like a personal essay than fiction. It doesn’t really work unless we picture the narrator as Susan Sontag. Much better is “Baby,” which is told through a set of parents’ statements to some kind of family therapist, but jumbled up so that the child they describe is at once seven and in his twenties and a baby and a teen. Again, like “Project for a Trip to China,” “Baby” takes all of its force from its form. It’s an experiment, rough but overall successful, though you can tell that Sontag isn’t quite in control.

“The Way We Live Now,” in contrast, is a more successful marriage of form and content. It is about a man who is very sick with HIV/AIDS—more specifically, it is about his friends and their discourse around their ill friend. Instead of conversation with the man, Sontag gives us telephone calls, gossip about who knows what, the intimate fear that one is “jockeying” for the best spot at the bedside, wanting to be the most needed.

In her famous comment that white civilization is a cancer, and then throughout the books Illness As Metaphor and AIDS and its Metaphors, Sontag worries at the nexus of bodily experience and language. She writes that “there is peculiarly modern predilection for psychological explanations of disease,” which derives from psychology’s scientific flavor. Psychology is a “secular, ostensibly scientific way of affirming the primacy of ‘spirit’ over matter,” and it leads to our conception of cancer as an “evil, invincible predator, not just a disease.”

“The Way We Live Now” extends this analytical work into the way we speak, presenting the lived experience of HIV/AIDS as one that is mediated by both the community of the sick person and the sick person himself. In one long run-on sentence, Sontag shows the looping reciprocity of illness and language:

And it was encouraging, Stephen insisted, that from the start, at least from the time he was finally persuaded to make the telephone call to his doctor, he was willing to say the name of the disease, pronounce it often and easily, as if it were just another word, like boy or gallery or cigarette or money or deal, as in no big deal, Paolo interjected, because, as Stephen continued, to utter the name is a sign of health, a sign that one has accepted being who one is, mortal, vulnerable, not exempt, not an exception after all, it’s a sign that one is willing, truly willing, to fight for one’s life.

HIV/AIDS is at the heart of this sentence. Language and the sick body are perfectly coextensive. And the disease is wrapped in the tangled and frantic community of speakers who veer between loving the sick person and speaking on his behalf.

“Project for a Trip to China” fails where “The Way We Live Now” succeeds, illuminating both the gaps and the genius in Sontag’s fiction. Both stories are formally inventive, almost overformalized in their strict conceits. The writing in Debriefing is never less than viciously good. But the quality of the stories’ ideas varies wildly. The care with which Sontag interrogates the desires and fears animating these stories distinguishes the good ones from the bad. “The Way We Live Now” tests the story form in a way that leads into the emotional heart of living in a plagued community. The ideas at its end represent a progression from the ideas at its start, having moved through a crucial pivot: “boy or gallery or cigarette or money or deal, as in no big deal.”

What do we learn about great intellectual Susan Sontag from reading these stories? In Debriefing we see a writer who was confident enough, and knew herself well enough, to try and try again, and develop when she failed. There are stories in this book that aren’t worth reading at all, but they have been gathered together because “Susan Sontag”—the posthumous cartoon version of the person—is big enough to demand it. But in this book there are also are moments of real certainty, even truth. As with every type of Sontag’s writing, you should expect value rather than consistency.