Lisa Waters was 25 years old when, one day in 1995, she couldn’t raise her right arm without pain in her shoulder. Blood tests revealed she had a rare autoimmune liver disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, that can cause liver failure but can be delayed or even forestalled with medication. For the next two decades, Lisa took a drug, Urso, thrice daily and remained in good health. She rose through the ranks at The Gap, eventually becoming a senior vice president, and later left the company to focus on raising her four children in New Jersey.

All was well until one day on Thanksgiving weekend two years ago, when she began vomiting blood for no apparent reason. A friend rushed her to the hospital. “If I hadn’t gone, I probably would have died,” she told me. Doctors at Manhattan’s Mount Sinai Hospital told Lisa that her PBC had progressed and she might need a liver transplant soon—if she could get one in time.

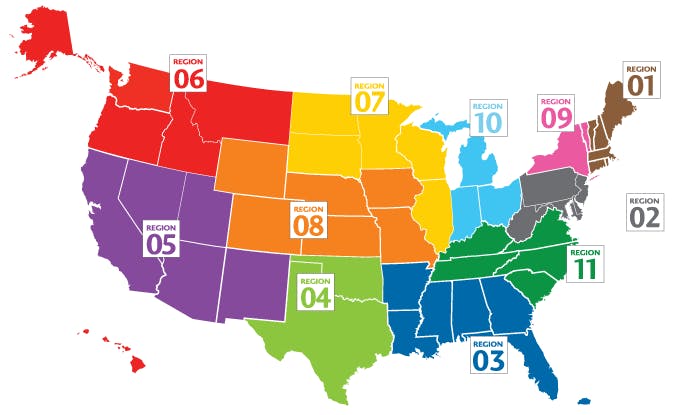

There’s a nationwide organ shortage. More than 115,000 Americans are on waiting lists for organs—mostly kidneys and livers—but because of how transplants are regulated, the severity of the shortage varies by geography. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the government-sanctioned organization responsible for allocating organs, divides the country into eleven regions; for the most part, organs must be transplanted within the same region in which they’re donated. But not all regions are equally in need. The two regions that encompass the Deep South’s “stroke belt,” for instance, have less severe liver shortages than elsewhere because of a combination of higher supply and lower demand.

Lisa had the bad luck of being treated Region 9, where livers are harder to come by. She faced a long waiting list. Being affluent, though, she had more options than the less fortunate candidates in her region. Since UNOS can’t restrict transplant candidates like it does organs, her doctor suggested she get listed in a region with a higher organ supply, to increase her odds of survival. Doing so isn’t simple or cheap. Some hospitals require patients be local for testing purposes, be immediately accessible in case an organ becomes available, and live in the area for up to three months for recuperation, with a caregiver. Out of pocket, liver transplants can cost more than $565,000; even the best insurance plans rarely cover anything beyond the operation and brief post-operation hospital stay.

Lisa chose Duke University Hospital in the mid-southern Region 11, which has a shorter waitlist for livers than Region 9. Her doctors told her that if an organ freed up, she would need to be at the hospital within hours and remain in the area for several weeks for post-operation testing and monitoring. So she moved into a two-bedroom apartment in Raleigh with her sister, who took a leave of absence from work to be her caregiver. Had Lisa stuck with Mount Sinai in New York, she would have waited one to two years for an organ. But just 10 days after moving to North Carolina, she got a call from Duke. A liver was available.

“Transplant tourism” usually refers to the practice of wealthy people traveling abroad for a new organ. But Americans engage in domestic transplant tourism, too. According to a New Republic analysis of data compiled by UNOS that catalogues organ transplants in the United States, between 2014-2016 there were at least 10,161 out-of-region transplants—nearly 11 percent of all transplants. One study found that from 2008-2013, 2,355 liver transplant candidates—8 percent of the total—travelled greater than 100 miles to other regions to get a transplant. Americans who can’t afford to do this, and who live in an organ-starved region, are left to wait—and often die as a result.

For two decades, transplant surgeons in these regions have pushed UNOS to reduce these geographic and economic disparities. “It’s supposed to be about fairness—equal need should have equal opportunity—but it is often about money and transplant centers protecting their self-interests,” said Sander Florman, a transplant surgeon at Mount Sinai. “It’s disgraceful.”

UNOS has considered more than 60 reform proposals in the last five years alone—and rejected all of them. It’s been difficult to reach consensus due to familiar geopolitical divisions. Defenders of UNOS’ system, mostly in the relatively organ-abundant Midwest and South, argue that the regional discrepancies are overstated, and accuse hospitals in states like New York and California of doing a poor job of procuring organs. Advocates in poorer states with lesser shortages say they shouldn’t have to ship organs to their richer counterparts. “Organs should stay in their local region,” said Seth Karp, director of the Department of Surgery at Vanderbilt University.

But organs are already going to people outside their regions. They’re just going to transplant tourists instead of the neediest patients.

The transplant era began in 1954, when the first successful kidney transplant was performed in Boston. Livers, hearts, and pancreases followed in the 1960s. In the 1970s, medical breakthroughs in organ preservation and transplant rejection allowed patients to live longer and organs to be shared statewide and even regionally. In 1983, the Food and Drug Administration approved a key anti-rejection drug, cyclosporine, which spurred an increase in transplants. The following year, Congress mandated the creation of a network to “assist organ procurement organizations in the nationwide distribution of organs equitably among transplant patients.” Thus, UNOS and its eleven regions were established.

More than 30 years later, technology has advanced, so that livers and kidneys can now travel by ground, planes and helicopters (and perhaps soon by drone) and remain viable for more than 12 hours. This makes the existing boundaries obsolete. “The regions are useful for administrative purposes, but not for determining organ allocation,” said James Burdick, a surgeon at Johns Hopkins and an UNOS president in the mid-1990s. “We’re still thinking in those old-fashioned terms of sections of the country.” The regional inequalities also contravene federal guidelines mandating “that allocation of scarce organs would be based upon common medical criteria, not accidents of geography.”

In 2014, a proposal to reform UNOS’ policies inspired transplant centers in Georgia, Kansas, Iowa, and Texas to form Keep Transplants Fair, a coalition whose members have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars lobbying Congress to oppose changes to the UNOS system. The following year, hospitals in New York, Baltimore, Massachusetts, and Connecticut formed the Coalition for Organ Distribution Equity, which hired Washington-based lobbying firm Thorn Run Partners to obtain “reforms to the system for distributing organs for transplant.” CODE has spent $260,000 on lobbying Congress and on “public education.”

This summer, UNOS considered a plan to allow patients within 150 nautical miles of a donor hospital to qualify for a transplant, even if the candidate is in another region. This would have provided low-income patients with more options and reduced the incentive for people to travel to other regions, but met stiff resistance from states who benefit from the current system. On October 10, at a meeting in Chicago, UNOS’ liver committee voted unanimously against the proposal. Doctors on the coasts felt it did too little to address discrepancies, while doctors in between thought it went too far. “Financial interests can rule the day in trying to move forward or to block [change],” said California surgeon Ryutaro Hirose, a former chair of UNOS’ liver committee and the co-author of the proposal.

The UNOS committee voted instead to adopt a much weaker plan from George Loss, a doctor at Ochsner Hospital in New Orleans. His proposal, which will be voted on by UNOS’ Board of Directors in early December, calls for shipping organs only when patients are on the verge of death, affecting very few of them and effectively leaving the existing system intact. This plan “all but ensures that where one lives will continue to determine the opportunity for liver transplant for patients with equal need,” said Florman, the transplant surgeon at Mount Sinai. “This is change, but it isn’t really changing anything.”

Angie Compton was a mental health therapy aide in her mid-30s when, about a decade ago, she and her new husband decided to move from Virginia to upstate New York. Around that time, doctors discovered she had Lupus, an autoimmune disease that was damaging her liver. As with Lisa Waters, Angie’s illness progressed slowly. She was able to function normally for a long time, but that changed in 2016. Angie’s doctor told her she needed a transplant. Her friends and family members were tested to see if they could be donors; all came back negative. Since Angie lived in Region 9, where livers are in short supply, her doctor suggested she get listed elsewhere.

At the beginning of 2017, Angie was getting ready to move to Georgia, in the hopes of receiving a transplant from Atlanta’s Emory University Hospital. But the hospital wouldn’t accept her insurance. Like about 20 percent of people on the transplant waiting list in New York, Angie was on her state’s Medicaid, which doesn’t cover organ transplants in other states—and she couldn’t afford to pay out-of-pocket for a transplant in another region. Unable to travel for an available organ, Angie Compton died on January 6 at the age of 43. Multiple studies detail that Compton was far from alone. According to a 2014 study in the journal Clinical Transplantation, “Patients with Medicaid health insurance were significantly more likely to die on the waitlist than those with other insurance,” and “those who received transplants elsewhere had significantly higher incomes than those who died on the waitlist.”

“Celebrity or financial status are not factors in getting a transplant,” UNOS states. Transplant travelers belie this claim. A 2013 study in the journal Transplantation found that “patients who were able to travel had a 74% increased likelihood of transplantation resulting in a 20% reduction in the risk of death…” The inequities in organ transplants are racial, too: A 2009 study in the American Journal of Transplantation found that Hispanics are less likely than whites to receive transplants, and “these disparities are attributable to geographic differences in organ availability.” A different, 2015 study found that “migrated patients were more likely to be male, of white race … and to have private insurance.” Yet another study determined that patients listed at multiple centers tended to be white, older, highly educated, and have private insurance.

Transplant tourism also acts as a perverse incentive for hospitals in relatively organ-rich regions to maintain the status quo, since they benefit from transplanting well-insured, otherwise healthy patients who require less expensive care and survive longer, thereby boosting hospital ratings. Patients with state Medicaid are likelier to have other health problems, dragging down hospital ratings and driving up health costs. “They are clearly selecting people of means,” said Raphael Merriman, a liver specialist at California Pacific Medical Center.

Lisa Waters’s move to North Carolina likely saved her life. She received a successful transplant, and spent four weeks recovering in her Raleigh apartment. “Financially, you have to be able to pay for the stuff that your insurance isn’t going to cover, like renting a place to stay, all your food, all that,” she told me. Now back in New Jersey, she spends nearly $40,000 annually on insurance and takes dozens of pills a day, but feels great. “It was so easy for me,” she said. “For so many people, they just don’t have the option…. The reality is a lot of people just don’t end up getting an organ.”