On Tuesday, the National Park Service announced a proposal to sharply increase entry fees to 17 of America’s busiest and most iconic national parks. Starting next year, it would cost cars $70—instead of $25 or $30—to enter public treasures like Yellowstone, Yosemite, Shenandoah, and the Grand Canyon during peak season. President Donald Trump’s secretary of the interior, Ryan Zinke, said the money is needed to repair the parks’ roads, campgrounds, and bathrooms. “The infrastructure of our national parks is aging and in need of renovation and restoration,” Zinke said, adding that higher fees “will help ensure that [the parks] are protected and preserved in perpetuity and that visitors enjoy a world-class experience that mirrors the amazing destinations they are visiting.”

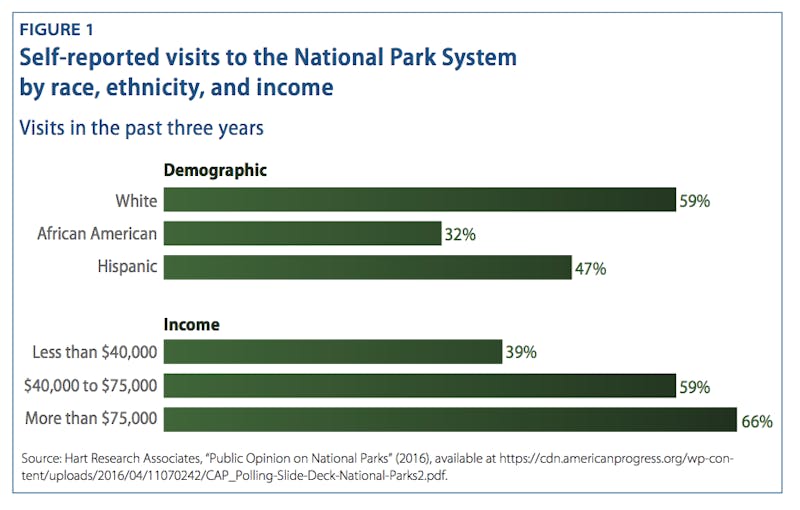

Though Slate was predictably contrarian in defending the move, most critics rightly worry that the fee hikes will price out lower-income Americans, who are already underrepresented among visitors to national parks. “One of the basic ideas from the very beginning was that parks would be accessible to all Americans regardless of income level,” Jim Northrup, until recently the superintendent of Shenandoah, told ThinkProgress. “Americans already own these parks and they shouldn’t have to empty their wallets to enjoy them,” said Senator John Tester, a Democrat from Montana. Maureen Finnerty, chair of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, said in a statement, “The enormity of the increases exceeds any increases in the history of the National Park Service. We were shocked when we read the Administration’s proposal.” Meanwhile, the Trump administration has proposed steep budget cuts to the National Park Service, and the House’s appropriations bill cuts it slightly. (The Senate has not released its specifics.) But if the agency needs money so badly, why slash its budget?

While there’s bipartisan concern on Capitol Hill about the fee hikes—the Senate may hold a hearing on it—another proposal this week that affects national parks has gone largely unnoticed. A Department of the Interior report on Tuesday, a response to Trump’s executive order in March on “promoting energy independence and economic growth,” outlined its plan to ease the leasing of federal lands to fossil fuel companies for mining and drilling—namely by reducing environmental oversight and limiting public input. Some of this land is directly adjacent to America’s national parks. As Nicholas Lund, a senior manager at the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), told me, “What happens next to a park impacts a park.”

So Zinke is not only trying to make national parks more expensive to access; he’s also threatening to degrade the quality of some of those parks—and of the visitors’ experience, the cost of which has more than doubled. Imagine dropping $70 to enter a public land, only to reach an overlook and see a magnificent valley of ... rigs and pumps. You hear the cacophony of industrial equipment. You take a deep breath: the whiff of oil.

Generally speaking, the federal government is not allowed to lease national parkland for oil and gas development. But fossil fuel development doesn’t have to happen inside a national park for the national park to be affected. In 2002, an oil well in Tennessee exploded, sending thousands of barrels of crude flowing into tributaries of the Obed Wild and Scenic River, part of the national park system. The fire from the blowout “burned oil-soaked vegetation, trees and soils and caused underlying rock to fracture,” according to Interior. “Spilled oil continued to seep from the creek bank into Clear Creek for 5 years after the incident.”

Big accidents aren’t the only problem. “It’s about the degradation of your experience in the park,” Lund said, noting how things can change when a relatively untouched place becomes semi-industrialized. “There are sound impacts, light impacts, it can affect wildlife movement inside and outside of the park.” And with the Trump administration trying to rescind clean air regulations on oil and gas development, Lund said, “Air quality is certainly a problem.”

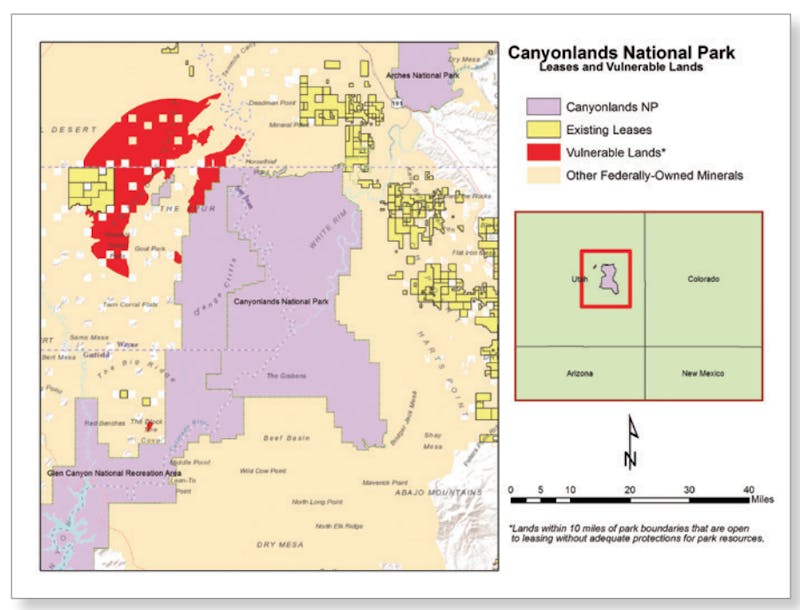

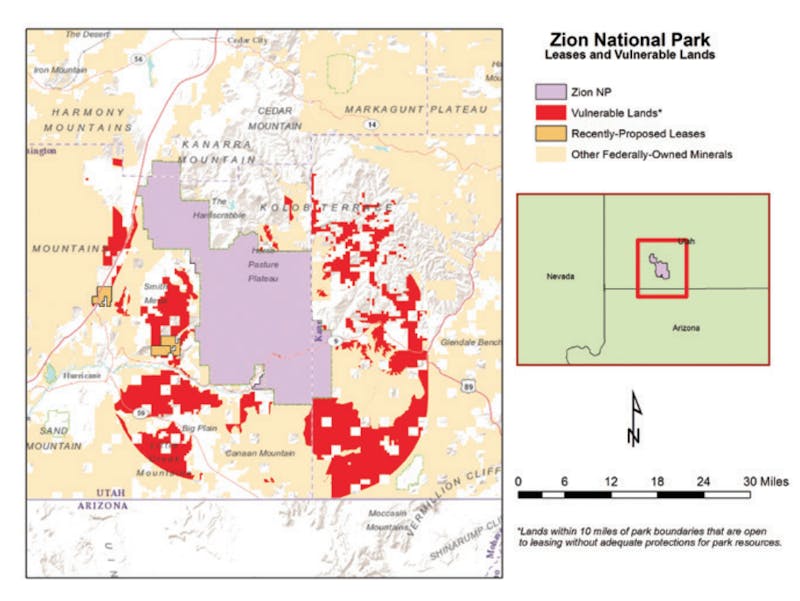

Of the 17 national parks slated for fee hikes, three are particularly vulnerable to increased oil and gas leasing on their borders: Arches, Canyonlands, and Zion. All three are in Utah and are surrounded by what are known in the energy sector as “hot plays”: areas that could be particularly lucrative for development.

These lands were vulnerable before the Interior’s Tuesday report, because the Bureau of Land Management, which is within Interior, has been far more aggressive about leasing public lands to oil and gas companies than previous administrations were. Whereas the Obama administration rarely held lease sales, Zinke is making sure BLM holds them quarterly. Zinke is also accelerating the approval process, aiming to give companies their permits within 30 days, down from the 257-day average under Obama.

At least two national park–adjacent lands have been floated for leasing under Zinke. As part of its September lease sale, BLM proposed several parcels near Zion National Park where oil and gas development is rare. The parcels, according to NPCA, bracket a road “which receives intensive use during summer months, when many tourists use it to access the upper plateaus of Zion National Park.” The agency has also proposed leasing land next to Utah’s Dinosaur National Park. Both lease proposals faced significant opposition from conservationists and the public, and were ultimately deferred.

But Zinke, following Trump’s order, now plans to reduce public input in these lease decisions—specifically by killing an Obama-era program called “master leasing plans,” a form of conflict resolution for drilling operations near national parks and other sensitive recreational and cultural areas. An MLP brings together various stakeholders—representatives of the tourist, recreation, and oil and gas sectors—to ensure that leases don’t, say, cut through bike paths, disrupt the natural soundscape, or interrupt breathtaking views.

But BLM expects to rescind the program by the first quarter of the 2018 fiscal year, according to Interior’s report. “The agenda outlined in the agencies’ reports will almost certainly bring unrestrained industrial energy development to the lands and waters at the doorsteps of America’s national parks,” said Mark Wenzler, the NPCA’s senior vice president for conservation programs, in a statement. Indeed, though the leases near Zion and Dinosaur were deferred, both parcels could come up again for consideration. Any “hot play” near a national park could.

Increased oil and gas development will not impact every national park facing a fee hike, but other Zinke policies might. In June, he proposed privatizing campgrounds in national parks. “As the secretary, I don’t want to be in the business of running campgrounds,” he said in a speech to the recreation vehicle industry. “My folks will never be as good as you are.” Indeed, Zinke has indicated a willingness to turn many park services over to private corporations, making public lands just a little less public.

According to Zinke, the goal in leasing more public land and privatizing services is to raise revenue for the federal government. And yet, the administration claims that these money-generating measures still aren’t enough—that Americans must pony up even more for parks that are becoming less public and less pretty. It’s a classic Trump scam: Make us pay more for something of lower quality, then tell us we’re getting a great deal.