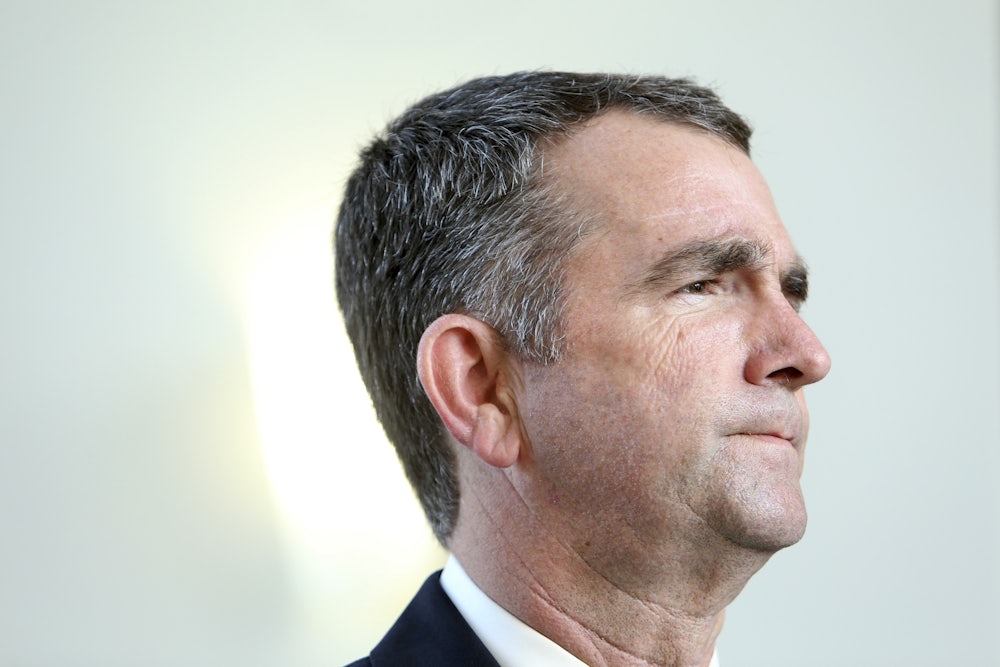

On Thursday night in Richmond, Virginia, his first day back on the campaign trail since Donald Trump’s inauguration, Barack Obama will give a stump speech for the state’s Democratic nominee for governor, Ralph Northam. The former president will inject himself into a race The Washington Post called “the country’s marquee statewide election this year,” a critical swing-state test for his party and the Trump resistance. Polls are tightening; Democrats are nervous. But with three weeks until the election, Northam, Virginia’s current lieutenant governor, is clinging to a slim lead. His campaign said last week that “Ralph and President Obama will discuss the need for the next governor to create economic opportunity for all Virginians—no matter who you are or where you’re from.”

One subject the pair likely won’t discuss, however, is their differences on K-12 education, the issue one recent poll found is most important to voters in the race. Northam represents a distinct departure from Obama’s emphasis on charter schools, support for high-stakes standardized tests, and tense relations with teachers unions. In fact, the lieutenant governor has explicitly deemphasized charters and critiqued the testing regime, while unions have sung his praises. His campaign is at once the first big battle against the privatization agenda of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—whose family gave more than $100,000 to his Republican opponent, Ed Gillespie—and a kind of prototype for left-wing critics of Obama’s education agenda who hope Democrats will chart a new course on public schools.

“Northam is a breath of fresh air,” Diane Ravitch, the education historian and activist, told me this week, lauding him as “what every Democrat should be” on school reform. Julian Vasquez Heilig, an education professor at California State University, Sacramento, said Northam’s campaign is “a bellwether of what you’re going to see in other governor’s races,” including Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom’s candidacy in the Golden State next year. “There really is, for the first time in a statewide race, this opportunity to make a decision between the Betsy DeVos vision of privatizing and cutting funding for public education as public good versus someone who has more interest in a local community approach and listening to some of the critiques of the past 15 years of failed top-down education policy,” he said. Northam spokesman David Turner told me, “For obvious reasons, I’m not going to be discussing differences with President Obama right now.” But in Vasquez Heilig’s view, Northam represents “where the new wave of Democratic leaders are going.... He is breaking from Barack Obama and he is charting a different course from Trump and DeVos.”

Talk of a seismic shift in the Democratic Party’s education policy is premature. But with DeVos making “school choice” like charters and private school vouchers increasingly toxic for Democrats, there’s certainly room for a stronger defense of public education on the left. Yet as Northam is learning late in this campaign, pushing back on decades of accepted wisdom can be politically perilous.

Almost exactly a year ago, as the Obama presidency wound down, Washington Post education blogger Valerie Strauss wrote that “the growth of charter schools was a key priority in his administration’s overall school reform program.” The president had incentivized the expansion of these publicly funded but independently operated schools, which proponents say give students an alternative to failing traditional schools. But earlier this year, neither Democrat running in Virginia’s gubernatorial primary campaigned on expanding charters in the state.

In a June “email debate,” Post editorial board member Lee Hockstader asked both Northam and former Congressman Tom Perriello “why you want to continue to keep [charters] out of Virginia when there are schools in many communities that have so consistently failed their students—many of them in predominantly black and low-income areas—and when there is no hope of change or improvement.” Northam replied that “we need to make sure that we fund K-12 first before we move on to other things like charter schools.” He stressed that any charter authorization decisions should be “left to our local leaders and those closest to the communities,” and that “the charter proposals seen in Virginia would ultimately divert much-needed funding from school divisions, often those that are in the most need.”

Perriello’s rhetoric was even more cautious. “The performance of charter schools has simply not exceeded performance within the system, despite years of investments,” he told the Post. “The evidence does, however, show one clear trend, which is that schools in areas of concentrated poverty are far more likely to be underperforming.” He then went on to say, “Instead of blaming the teachers and principals, we should ask why we have not done more to reduce poverty.... Some of the solutions to our education performance must be found outside the classroom, in restoring the broken promise of social mobility and economic security for all Virginians.”

This kind of rhetoric might have endeared Perriello to the Virginia Education Association, which represents 50,000 educators in the state. But in April, the group swung its weight behind Northam, saying, “He’s the best candidate for our students, schools and educators, and he has an excellent track record of working to meet their needs.” The reference to his track record was telling. Though Perriello ran on skepticism of charters, even his past ties to “school choice” advocates like the Democrats for Education Reform was enough to turn the union off. “There was some extreme concern with regard to that issue,” the union’s president, Jim Livingston, told me. “That issue did play a significant role in our decision to embrace Ralph Northam.”

Livingston says Northam will be a better partner for teachers than Obama’s education secretary, Arne Duncan, was. “Northam understands that in order for us to move the needle on improving public education we have to include the practitioners,” he said, “and that’s something we did not see under the Arne Duncan years, and it’s something we certainly will not see under the Betsy DeVos administration.” Livingston added that Northam “provides us with the opportunity to turn away from that failed experience and really move in a new direction.”

Northam also provides a stark contrast with Ed Gillespie, who has fully embraced DeVos’s privatization agenda. “Gillespie wants to expand the state’s charter schools beyond the eight in operation,” the Post reported. “As a state senator Northam voted against loosening restrictions that govern the establishment of charter schools, and as a candidate for governor he has advocated investing in traditional public schools.” Meanwhile, Gillespie supports education savings accounts, which are basically a backdoor private school voucher scheme diverting money from public schools. According to Turner, Northam’s spokesman, DeVos looms large in the minds of many voters in this race. “I have never seen a cabinet member with the name ID of Betsy DeVos,” he told me. “Honestly, I don’t know how it happened.”

Which isn’t to say Northam has completely avoided political minefields with all this talk. In a recent interview with the Post editorial board, which has long been a champion of “school choice” and other market-driven education policies, he critiqued Virginia’s standards for student accountability under the federal No Child Left Behind law. “What would replace them?” the Post asked. “Astonishingly, after almost four years as lieutenant governor and a month away from the election, Mr. Northam had no answer.”

Particularly concerning was Mr. Northam’s view that because children are diverse, “coming from different backgrounds and different regions,” he’s “not sure that it’s fair” to give them all the same test; they shouldn’t be penalized, he said, for the environment they come from. The suggestion that some students should be required to pass one type of assessment, while others are given a different (presumably more rigorous) one, is disconcerting. There is no question that some children come to school handicapped by circumstances not experienced by their better-advantaged peers, but children do better when there are high expectations. Creating different expectations for children does them no favors; it just allows adults to escape responsibility.

The Gillespie campaign and Republican Governors Association both hyped the editorial. Samuel Abrams, director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at the Columbia University Teachers College, told me he was surprised Northam didn’t have a response about an alternative accountability system. “This is kind of baffling to me,” he said, even if Northam is “on the right track” with his statements. “I think what Northam is cognizant of, clearly, is there are perverse consequences to high-stakes testing. It crowds out time for subjects that aren’t being tested and generates a lot of undue stress for parents and teachers and students.” Turner said that Northam “feels like the system went too far and put too much emphasis on standardized tests,” and that he plans to work with teachers to find a “balanced approach.”

Ravitch defended Northam’s statements to the Post in a blog post. “What’s the ideal accountability system?” she wrote. “Northam admitted to the editorial board that he doesn’t know.... What doesn’t work is one-size-fits-all standards like Common Core. What doesn’t work is promising rewards or threatening punishment to teachers and principals, tied to test scores.” This may be true, but in a tight race where education is at the forefront of voters’ minds, it’s political malpractice for a candidate not to have a solution in mind. Northam’s slip could prove to be a cautionary lesson, especially if he ends up losing to Gillespie: As Democrats energize voters by railing against DeVos, while also breaking with the education policies of its party’s past, they had better have an answer to what the future should look like.