This is a strange time for a genre of American history that is sometimes derisively referred to as “dad history.” These approachable tomes about the great men of the past are a fixture of airport bookstores and Barnes & Noble wishlists, and they have never been more popular or lucrative. David McCullough’s John Adams became an HBO miniseries. Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton became Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit Broadway musical. Many of these titles—particularly Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals—have transcended their genre, becoming fodder for entrepreneurs and the managerial class. After all, who better to teach us the lessons of leadership than the greatest leaders ever?

But even as dad history has reached its cultural zenith, it has never seemed more out of step with the times. Advances in historical scholarship have brought more attention to the plight of Native Americans, African Americans, women, and other marginalized groups. Greater attention is being paid to the original sins of the United States—slavery and genocide—and the way they have reverberated across the centuries. The best works of recent narrative history, such as Edward Ayers’s The Thin Light of Freedom and Heather Anne Thompson’s Blood in the Water, have focused on ordinary Americans’ contributions to seismic events, a ground-level viewpoint that is at odds with the Great Man perspective.

And then there is the current occupant of the White House, whose “I alone can fix it” approach to governance should give Great Man historians pause. If there was ever evidence that history is moved by broader forces, as opposed to the talents of any one individual, Donald Trump is it. And the emergence of Trump as the country’s preeminent political figure is a sure sign that those original sins are very much still with us.

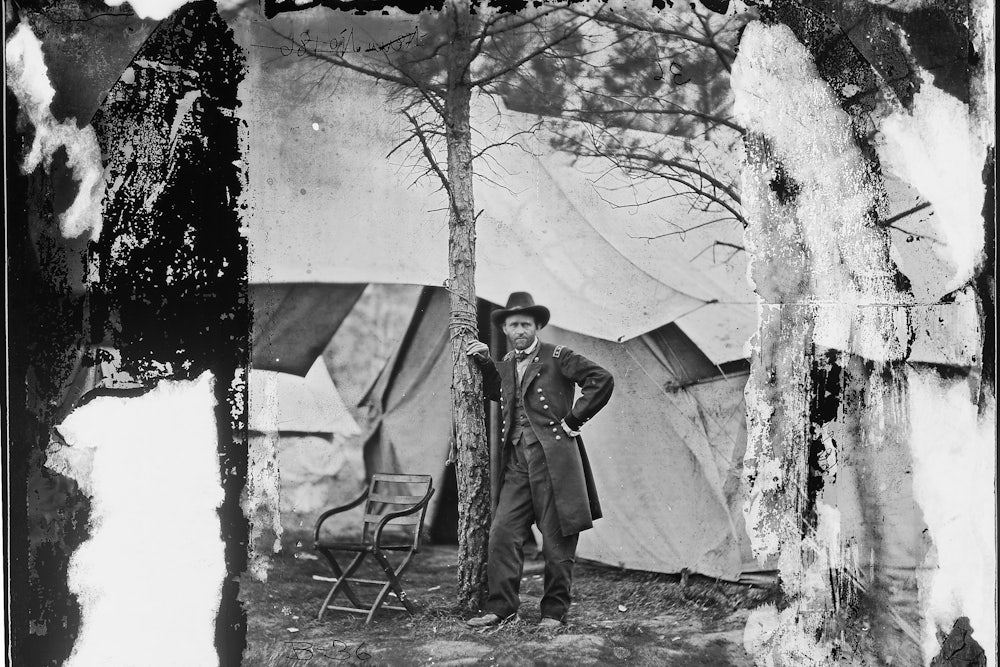

Chernow’s new book, Grant, is deft at navigating these tricky currents. Coming in at a well-paced but absolutely gargantuan 959 pages, Grant is a stirring defense of an underrated general and unfairly maligned president. Its great contribution to the popular understanding of the Civil War and its aftermath is to expose the roots of the longstanding bias against Grant: White southerners and their allies wanted to portray Reconstruction as a tragic folly, rather than a radical and unfinished revolution.

To be sure, a sympathetic treatment was to be expected: Chernow is enormously defensive of his subjects. Alexander Hamilton and Washington: A Life are both handicapped by his refusal to acknowledge any flaw (elitism and slaveholding, respectively) without heavy qualifications. He has often been praised for humanizing marble men, but in fact Chernow is uncomfortable with their shortcomings, which leads him to create marble men that are merely a little more lifelike. Secondary characters often suffer, because his subjects’ enemies often become his enemies. Chernow’s work is best understood as a kind of modern myth-making, updating the stories of America’s past in ways that make them come alive in the present.

In Grant he is aided enormously by his subject’s extraordinary life. The book tracks his struggles as a civilian; his incredible and rapid rise during the Civil War; his unexpected fall at the hands of the con man Ferdinand Ward, the 19th century’s Bernie Madoff; and, eventually, the writing of his memoirs, one of the greatest works of American literature. (Ironically, the strength of The Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, which have just been reissued in a very helpful annotated edition, may have delayed the recognition of Grant’s genius by discouraging potential biographers.)

For a book that seeks to set the record straight, it is also aided by the flimsy but strongly held myths about Grant, nearly all of which can be sourced to critics of Reconstruction and Lost Causers: that Grant was a butcher who only won victories because of the North’s technological superiority and numerical strength; that his presidency was defined solely by corruption; that his lifelong struggle with alcoholism was deeply debilitating.

Despite writing very long books, Chernow is not one to get bogged down in anything that isn’t the main plot. Fort Sumter is fired upon on page 123, while the next 15 years constitute 735 pages, meaning that Grant’s first 40 years and final decade get about 100 pages each. This makes for a propulsive and focused book, but it does have its drawbacks, particularly when it comes to filling out Grant’s elusive character. This is most evident when the discussion turns to his flaws, about which Chernow is characteristically apologetic.

Grant has been universally praised for his composure under pressure and in the heat of battle, but he was a sucker who was repeatedly betrayed by people close to him and who was easily connived out of money. Chernow is as mystified by this trait as Grant’s contemporaries were. His odious General Order No. 11, which expelled Jews from the military district under Grant’s control, is torturously explained as being aimed more at Grant’s opportunistic father, who had entered into business with Jewish businessmen in an attempt to profit from his son’s success.

Then there’s the vexing issue of Grant’s alcoholism. Here, Chernow is, to his credit, remarkably sympathetic. He treats alcoholism as a disease that Grant largely overcame, rather than a personal failing. Once again he is defensive about his hero’s weaknesses, but in this case it is channeled in a useful way. Grant’s alcoholism was frequently used by his foes, many of whom opposed Reconstruction, to denigrate the man who was championing black labor and voting participation.

Chernow is most comfortable describing battles and landmark achievements, so it’s no surprise that his treatment of Grant’s role in the Civil War is the book’s most fully realized section. Other generals—Grant’s friend and sometimes frenemy William Tecumseh Sherman, Robert E. Lee, the despicable Nathan Bedford Forrest—are typically held up as the “geniuses” of the War. But Chernow persuasively makes the case that Grant was its most-forward thinking and innovative general and that, while he had equals as a tactician, his ability to manage, mobilize, and deploy enormous armies was unsurpassed. Chernow is also in fine form depicting Grant’s commitment to abolition, which grew dramatically during the course of the war and has not been adequately explained by other popular biographies. In Grant, Chernow patiently unspools Grant’s realization that the Civil War is about slavery and, ultimately, equal protection.

This leads to Grant’s real strength: its treatment of Reconstruction. It is portrayed as a continuation of the divisions that led to the Civil War, rather than a grace note, a national embarrassment, or a well-intentioned failure. Ken Burns’s 1990 documentary The Civil War, which made a maudlin case that the war ultimately brought the country closer together and largely ignored its aftermath, emerged right at a moment when the so-called revisionist interpretation of Reconstruction was ascendant. Grant breaks little new ground historically, but the fact that it treats Reconstruction as the beginning of a long, troubled fight for equality in America is nevertheless important.

Chernow can be too fatalistic at times. He excuses the failure to redistribute lands as politically impossible, and treats Grant’s retreat from Reconstruction in 1875 as a tragic inevitability, given that many in the North had tired of the military occupation of the South. The treatment of Native Americans during Grant’s presidency, meanwhile, is muddled: Chernow is torn between Grant’s assimilation-oriented Peace Policy and the reality that the president’s old friends Sherman and Phil Sheridan oversaw numerous massacres while under his authority. Chernow also tends to insulate Grant from his administration’s corruption, which he insists he knew little about. This helps keep the focus on Grant’s devotion to fighting for progress and against the Ku Klux Klan in the South, but also feels disingenuous—continuous scandal, in fact, damaged the administration’s credibility and helped undercut Reconstruction efforts.

But to his credit, Chernow is no sentimentalist. In past accounts (by biographers, but also in the kinds of folktales that usually pass for American history) Grant’s funeral symbolized a nation finally coming together after the Civil War: Grant’s coffin was carried by three Southern generals and three Northern generals, all of them united in grief. Chernow resists this familiar cliché, with an account of the funeral that is affecting but based in an ambivalent reality about what Grant was able to accomplish during his life.

Chernow underscores Grant’s tremendous efforts on behalf of the four million slaves freed during and after the Civil War, while acknowledging the fact that Reconstruction remains unfinished even today. Popular history emphasizes neatness and inevitable triumph in the face of adversity, and Grant’s presidency was neither neat nor triumphant. He was a complicated hero who won the Civil War but was never quite able to win the peace—or the ultimate promise of emancipation. By placing this imperfect hero at the center of a book sure to be found under the Christmas tree, Chernow has given us a rare kind of popular history: one that forces readers to confront hard truths, not just revel in America’s all too fleeting triumphs.