It was every bit as predictable as death, taxes, and alarming tweets from @realDonaldTrump. In August, the small-but-powerful remnant of big-money moderation in the Democratic Party, shaken but not stirred by Hillary Clinton’s defeat in 2016, officially declared war on the party’s left-leaning rank-and-file. Rising from the ashes of the defunct Democratic Leadership Council, the “centrist” movement that took over the Democratic Party after its three straight presidential defeats in the 1980s—and erased the last vestiges of New Deal liberalism from American political discourse in the name of winning elections—came a “new” effort called New Democracy, touted as a vehicle for “rethinking” the party’s message after its history-making loss to Donald Trump. But this grand reassessment, led by DLC co-founder Will Marshall and his K Street band of brothers, was merely a reassertion of the wealth-first economics, go-slow social progressivism, and hawkish foreign policy peddled by white Democratic power-brokers and Clintonian neoliberals for three decades now.

In a political age defined by two strains of populism—Trump’s on the right, and Senator Bernie Sanders’s on the left—New Democracy should be viewed by any sentient political observer as little more than a risible relic with a fancy budget. The most prominent Democratic politicians who’ve jumped on board are anything but prominent: John Hickenlooper, Colorado’s business-first governor, Tom Vilsack, the former Iowa governor and Clinton cheerleader, and New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu. But the old organs of the Washington establishment still take these people seriously, and otherwise intelligent Democrats still have a strange Pavlovian response to the dire warnings they issue, like clockwork, every four years: Embracing liberalism will always and forever end in defeat (even if Barack Obama disproved that theory not once but twice).

And so, last week, the Washington Post published an op-ed that disarranged the nerve endings of timorous liberals across the land: “Trump Is on Track to Win Reelection,” by professional Clintonite Doug Sosnik. (The last time Sosnik ventured such a bold prediction was in June 2016, when, even before the party conventions, he declared the election “already decided”—in Clinton’s favor.) Matt Yglesias at Vox, among others, hopped aboard this memetic bandwagon in subsequent days, offering up their own reasons why Trump’s “on track to win in 2020.”

Sosnik made one valid point: Trump’s “dismal” poll numbers nationally don’t reflect his standing in the battleground states that lifted him to victory in 2016. And indeed, the president’s numbers in Ohio and Michigan and Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are a bit less dismal than elsewhere. But Sosnik’s argument has little to do with facts. Toward the end of an article built on tortured logic and tendentious claims (“Trump enters the contest with a job approval rating that is certainly at least marginally better than what the national polls would suggest”), he finally comes around to his money shot: “So for Democrats and others who want to beat Trump, unifying behind one candidate will be essential.” Translation: Let the old, white, Democratic establishment pick its favorite for 2020, and everybody else get in line. Or else.

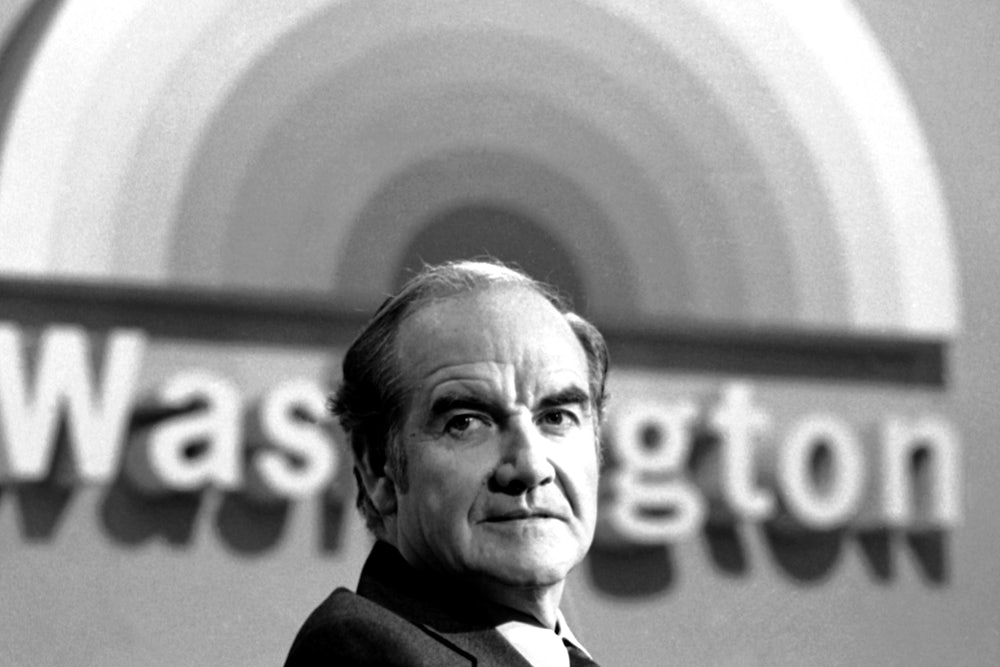

Or else what? Alan Greenblatt, a staff writer for Governing magazine and former NPR correspondent, provided an answer in Politico Magazine on Sunday with one of the most ludicrous pieces of political analysis you’ll find this side of Breitbart: “Are Democrats Headed for a McGovern Redux?” If that question sounds awfully familiar, that’s because it is. The “no more McGoverns” argument has been recycled and appropriated by anti-liberal Democrats—with nips and tucks to suit the needs of the moment—in practically every presidential election since 1972. They wielded it like a tiki torch against Jesse Jackson’s populist insurgency in 1988, and invoked it to torpedo Howard Dean in 2004. And after its ironclad logic failed to derail Barack Obama in 2008, the “McGovern threat” was revived with a vengeance against Sanders in 2016.

The goal of these disinformation campaigns has always been the same: to frighten the left into falling in line with the moneyed masters of the party. And at a moment when the party is finally abandoning the New Democratic formula—suck up to big business and the military-industrial complex, pander to white supremacy, and win!—fear-mongering is the only thin reed of hope the “moderates” have to retain their supremacy in the party.

For any Democrat of any stripe, the threat of a Trump reelection—and a second term free of any need to retain even his current 34 percent approval rating—is genuinely mortifying. By reviving the hoary old arguments about why McGovern lost to Nixon in one of the biggest landslides in American history, the old New Democrats aim to once again scarify a majority of Democrats into reluctantly backing a neoliberal championing wealth-first (sorry: “middle class”) economics and a bloodthirsty view of American power on the international stage.

But the notion that 2020 will bear any resemblance to 1972 is built on a foundation of counterfactual history and willful misreading of contemporary politics. The logic runs thus: Because Trump is the second coming of Nixon—“the avatar of white cultural-grievance politics,” as Greenblatt puts it—we must learn the lessons of how Tricky Dick managed to win reelection. The most important lesson, of course, is that the Democrats veered too far left after the narrow defeat of an establishment candidate (Hubert Humphrey, now played in this movie by Hillary Clinton) in 1968. Fueled by a “raging enthusiasm among younger voters”—yesterday’s Bernie Bros—liberals “made strategic errors that Democrats today appear hellbent on repeating,” Greenblatt asserts. They doomed themselves by turning to “the ultra-liberal Senator George McGovern”—now played by Bernie Sanders—thereby steering “a course too far from the country’s center of political gravity.”

There is barely a smidgen of truth to any of this—a fact that Greenblatt, who seems to possess some sense of fairness (or shame), highlights throughout his piece with one “caveat” after another. “Politics today are much different than they were then,” he admits early on, “as is the shape of the electorate. But there are parallels that Democrats should bear in mind as they nurse their hopes of driving Trump from the White House.” (Dear God: If all we can do is “nurse” a “hope” of defeating the least-popular and most inept president in American history, maybe we really are doomed.)

In the world of reality, President Trump bears about as much resemblance to President Nixon as he does to President Lincoln. It’s understandable, given the completely unprecedented nature of Trump’s political rise, that Americans were left grasping for the nearest analogy they could find. And it’s true that Nixon was fatally corrupt, paranoid, and socially awkward; he used racial code to exacerbate white people’s resentments and win their votes. Also, he probably committed treason, secretly torpedoing a peace agreement with North Vietnam, to get himself elected in 1968—just as Trump may have done by colluding with Russia in 2016.

The similarities end there. Nixon was an intellectually gifted, up-from-the-bootstraps product of a hardscrabble childhood, not a spoiled and ignorant child of privilege. In his long political career—congressman, senator, vice president, three-time presidential nominee, failed candidate for governor of California—he outworked, out-plodded, and out-strategized nearly everyone in his path to the White House (except for John F. Kennedy). His politics were in most respects the polar opposite of Trump’s: Nixon despised the “damned far right” of his party (though he certainly didn’t hesitate to pander to it) just as much as he loathed “the far left.”

And once he reached the White House, Nixon governed as what National Review’s John Fund called “the last liberal.” He signed the Clean Air Act, created the EPA and OSHA, imposed the “alternative minimum tax” the wealthy hate so passionately, and (smelling salts for Ron Paul, please!) took America off the gold standard. His first term produced more landmark progressive legislation than the 16 years of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama combined. And Nixon wanted to go further: He called for a minimum guaranteed income for all Americans—an idea too liberal for most liberals—and in 1972 ran on a “comprehensive health insurance plan” for all, including government subsidies for those who needed it. In the international realm, which Nixon knew and cared about the most, he barbarically and cynically ramped up the war in Vietnam—but he also negotiated a landmark arms-reduction treaty with the Soviet Union and opened relations with “Red China.”

He was nothing like Trump, in other words. As Nixon historian Rick Perlstein writes, “People want to grasp for the familiar in confusing times, but it’s often just an evasion of the evidence in front of them.” Elsewhere, he’s spelled it out more plainly: “Trump is Trump, people! TRUMP!”

Similarly, McGovern was McGovern—a “prairie populist” and war hero who ran to the left on a peace platform to secure his unlikely nomination. He conducted a general-election campaign that was a righteous mess from the get-go, overseeing a chaotic Democratic Convention that looked terrible on television and hastily tapping a moderate Democrat from the heartland, Thomas Eagleton, as his vice president, without the least bit of vetting. When Eagleton was forced to admit he’d undergone electric-shock therapy twice in the 1960s, McGovern made matters worse—and wrecked his reputation as the one honest politician in Washington—by first backing him “one thousand percent,” then coldly dumping him from the ticket.

The Democrats of 1972 were a party with far deeper fissures than the current edition, with its intramural squabbles between the center-left and the actual left. The Democratic power-brokers of the day—authoritarian bosses like the AFL-CIO’s George Meaney and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, along with foreign-policy hawks still gung-ho for the Vietnam War—were hardly “centrists.” (“They’ve got six open fags,” Meaney famously complained about the New York delegation at the DNC.) This “establishment” sat out the election once McGovern became the Democratic standard-bearer, denying their own party’s candidate the funding and get-out-the-vote machines that he had to have.

But what about Nixon’s Machiavellian recasting of McGovern as the candidate of “acid, amnesty, and abortion”? Doesn’t that sound like a Trumpian trick, just the kind of thing he might do to a Sanders or a Warren in 2020? Sure, except for the fact that it was moderate Democrats—namely, Eagleton himself— who actually originated that slander and bequeathed it to Nixon.

Nixon was the avatar of the “silent majority” of resentful whites, but he didn’t make it a pet phrase until he was already in the White House, and it wasn’t the main thing that got him elected or reelected. He won in 1968 by making a convincing (though dishonest) case that he was more likely than Humphrey to bring the Vietnam War to a speedy halt. And in 1972, he ran on an impressive record of progressive domestic policies, a landmark arms-reduction treaty with the Soviet Union, and the historic un-thawing of relations with China. Again, emphatically: not Trump.

The old New Democrats know perfectly well that the chances of Trump winning reelection in 2020 are approximately as good as the Democratic nomination going to Kanye West, with Kim Kardashian as his running mate. They know there’s no valid analogy to be drawn between Nixon and Trump, or between McGovern and the leading lights of the contemporary left, or between 1972 and the likely political climate of 2020. That’s why they’re scare-mongering again—because they are scared. Not of the depredations of the Trump presidency so much as the near-certainty that the next Democratic nominee will run on single-payer health care, progressive taxation, queer rights and abortion rights, and an anti-imperialist foreign policy. And they know the next Democratic nominee will almost certainly be the next president—and will chase them out of the party leadership once and for all.

The only thing that can prevent the Democratic left from ascending to power in 2020 is paying heed to the myth of McGovernism. Far from a time for timidity and caution, the rise of Trump and left-wing populism, combined with the repeated failures of the Clintonites, have combined to create a historical moment that’s more likely to resemble 1980 than 1972—the year when conservative Republicans, ignoring the voices of “moderation” in their own ranks, went with their hearts and minds and backed the radically right-wing (for his time) Ronald Reagan. Their politics then dominated the next 30 years of American history.

If Democrats fail to heed the real lessons of their own history—if they vote once again on the basis of their irrational fears rather than their noblest aspirations—they’ll have only themselves to blame. But it’s happened before. And hope, like falsehood, springs eternal in the New Democratic breast.