On a muggy June day, shortly before 4 a.m., a jeepney driver named Raul Domingo drove through Payatas, a hilly district in Manila’s sprawling suburbs. In the darkness, he spotted an obstruction up ahead: two nameless bodies, arms and legs splayed on the road, with cardboard signs around their necks. “I’m a robber,” the signs read. “Don’t emulate me.”

Such scenes have become common in the Philippines. Since President Rodrigo Duterte took office last summer, he has unleashed a crackdown on drugs and crime that has drawn international condemnation for its brutality. More than 7,000 people have died at the hands of police or masked vigilantes who roam the back alleys of Manila’s massive slums. “There are three million drug addicts” in the Philippines, Duterte has said. “I’d be happy to slaughter them.” His targets are drug dealers and users alike. In the slums, children sniff glue because it helps them forget the pangs of hunger. At the fish port, men rely on shabu, or methamphetamines, to stay awake during their 18- to 36-hour shifts. So, too, do the garbage pickers in Payatas, who spend hours each day searching for recyclable goods in the refuse. Under Duterte, these are capital offenses.

James Whitlow Delano, an American photographer who has reported from the Philippines since the early 1990s, returned to Manila in June to photograph the victims of Duterte’s drug war. “In Duterte, the people of the slums believed they had finally found their savior, their champion,” Delano says. “Instead he has unleashed masked assassins in a spasm of slaughter that has created a siege mentality in the slums, delivering assassination with impunity, without pause.”

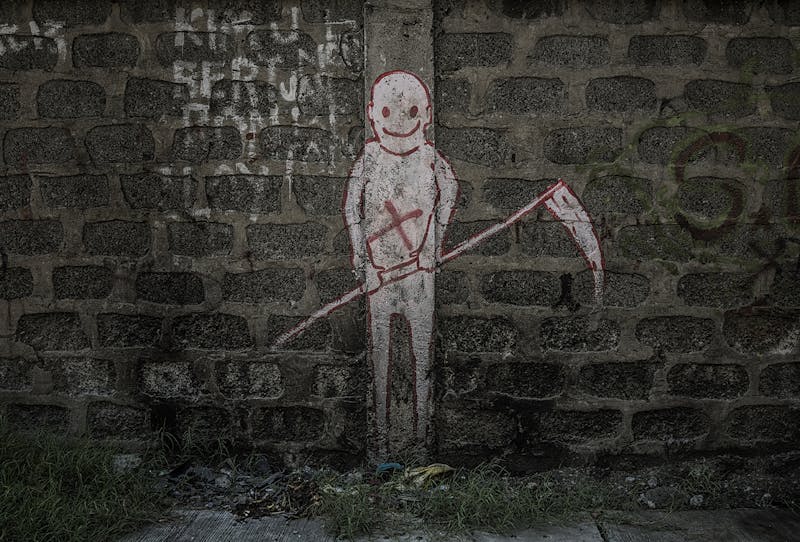

Graffiti on a wall on the main road just outside one of Manila’s slums. Last year, the police embarked on a nationwide campaign called Oplan Tokhang, knocking on doors of those suspected of drug use and “pleading” with the occupants to stop using. But the reality, critics say, is far bloodier.

Young men sniff glue hidden in a plastic bottle. Locals say assassins often use this back entrance to sneak into the port in Metro Manila’s Navotas, since the front gate is manned 24 hours a day by armed security guards.

A puddle of blood marks the spot where masked assassins gunned down Francisco Remedillo, a 68-year-old barbecue vendor, and Marlon Dela Cruz, his 36-year-old adopted son, in their little house in Metro Manila’s Quezon City. Dela Cruz was the intended target of the raid. But when Remedillo attempted to intervene, armed with a bat, he, too, was shot dead next to the only bed in their home.

Manuel Borbe’s blood runs into a storm drain after he was killed by unidentified masked men on motorcycles in the Holy Spirit district of Quezon City. According to his sister, Vivian, Borbe dealt drugs, but not by choice; he was forced into the drug trade to support his addiction to methampetamines, known locally as shabu.

Family and friends lift a coffin carrying Junmar Abletes—another victim of an extrajudicial killing—out of a hearse in Navotas’s Catholic Cemetery. Abletes, who was 27 when he died, had moved to the island of Samar, over 370 miles away from his home in Metro Manila. While back on a family visit, he was assassinated in the Market 3 slum in Navotas, where his family lives.

Saldi, 20, sits in the shack he constructed from plastic sheeting and scrap wood in Navotas. He began using methamphetamines to stay awake through his long shifts at the Navotas Fish Port. It’s a common route to addiction in Market 3, where people sometimes need to work 36-hour shifts to escape grinding poverty. Saldi says that he has lost 14 friends to unidentified assassins. And as a former methampetamine user himself, he worries that he may be next on the hit lists of drug users composed by local mayors in the slums.

A woman works on bookkeeping using the light of her phone in the Market 3 slum in the Navotas Fish Port Complex. Market 3 has electricity but no plumbing. Residents often turn to drugs to alleviate hunger and stay awake for the long hours they work at low pay.

Since Duterte took office, this tattoo has changed from a whimsical expression of irreverence to something that might draw uncomfortable attention.

After Sara’s husband Kulot was killed in Duterte’s War on Drugs, her home was burned down. Now, she lives in this former chicken coop in Navotas’s Market 3 slum. Her husband’s body was left in the morgue for over 25 days before being interred in a mass grave, because she could not afford a burial.

Graffiti on a wall next to a bridge in Navotas where victims of extrajudicial killings were thrown off of into a canal.

Reporting for this piece was facilitated by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.