Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go has several different directions: It looks backward, forward, and sideways. The setting is Hailsham, an academy strongly flavored by the British and postcolonial tradition of boarding school literature (“We loved our sports pavilion”). The novel flits past the canon of “school stories” like Tom Brown’s Schooldays, circles the Victorian classics of schooling (Jane Eyre, David Copperfield), and eventually settles on the wistful pastoralism undercut by dread that defines certain novels of patrician childhood: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Go-Between.

The plot, however, is dystopian. The residents of Hailsham are being bred for their organs. Such dystopias always gesture toward the future, because they imagine an alternate version of an actual past (for his part, Ishiguro mentions things like cassette tapes). Things that have not happened yet could always happen at some other time. Experimenting with the laws of the world, and looking toward how those laws might change one day, is a sci-fi gesture. The organ-farming of Never Let Me Go is a very similar intervention to the breeding program written by Margaret Atwood into the familiar world of The Handmaid’s Tale.

But by referring to a deep tradition of British childhood writing, Ishiguro blends his futurism with a whole other canon. He combines two full literary genres to create a third, which we can call Kazuo Ishiguro and nothing else. This is what enables him to look sideways in his fiction: He can describe things about our world that nobody else can. In Never Let Me Go, that thing, I think, is the crushing weight of circumstance on our lives. The place in space, history, and social hierarchy that we occupy is an accident of birth and a cage, Ishiguro shows—one that our humanity resists.

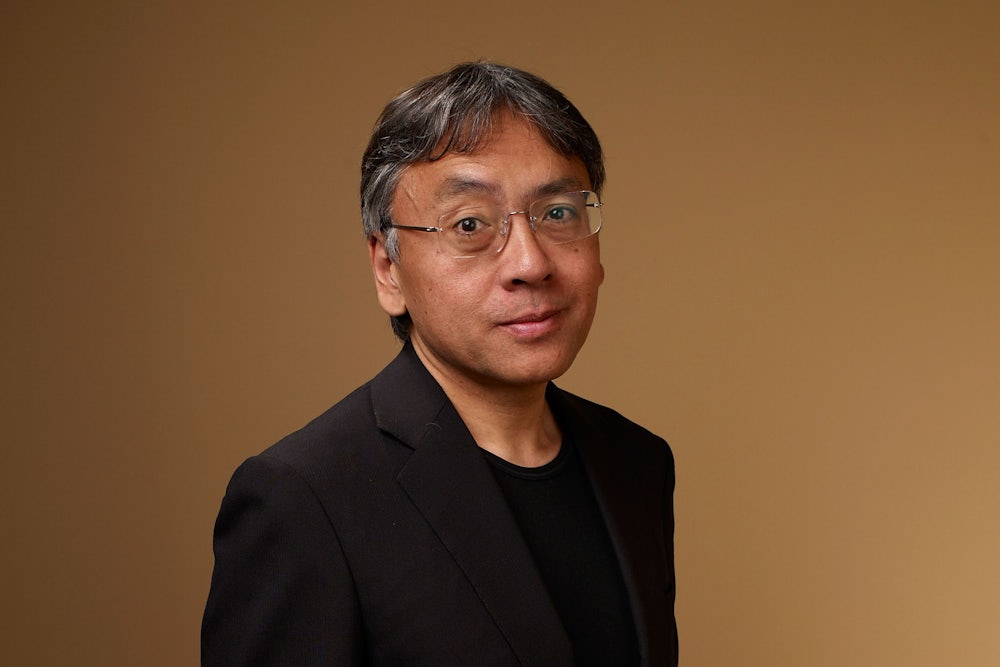

Ishiguro has won the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature. And with a prize like that comes some serious biographical thinking. There will be articles in the coming days and weeks that will weigh him up like meat on a deli scale, assessing who he is and what he means for the literary culture of our time.

Like the characters of Never Let Me Go, Ishiguro’s public identity has been crushed inside circumstance. The facts of his life, to many of his critics, are markedly racial. Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki in 1954. His family moved to England for his father’s job when he was five. In his early career, Ishiguro wrote what he has called “Japanese books, or at least books set in Japan with Japanese characters.” These include An Artist of the Floating World (1986), which follows a painter in post-war Japan recollecting his life, and A Pale View of the Hills (1982), also a novel of memory, in which a mother in England remembers a dead daughter to her living daughter, telling stories from the country she used to live in.

When The Remains of the Day came out in 1989, Ishiguro remembers that “people were startled by” his turn to English traditional material. In an interview with The Guardian, he describes how, “if you look at the reviews that came out at the time, and the comments made on review shows, this is what people talked about more than anything else—isn’t it extraordinary that this young Japanese guy should know so much about English butlers.” He recalls “a kind of surprise,” the palpable sense that “people are slightly uncomfortable that [he] made what they see as a jump, from being someone identifiably writing about [his] ethnic background, if that’s the word, to someone who wasn’t.”

In his Paris Review “Art of Fiction” interview, Susannah Hunnewell asks Ishiguro questions like “How typically Japanese were your parents?” and “Why did your family move to England?” In his 2005 review of Never Let Me Go in the London Review of Books, Frank Kermode notes that all six of Ishiguro’s novels to date are narrated in the first person. “Indeed this way of speaking seems appropriate to Japanese conversation, to the talk of a society in which manners are always important, and in which they might sometimes take precedence over candour. The characters do a lot of deferring and apologising, and even when they aren’t expressly said to be bowing gently to one another you can easily imagine they are.”

Where Ishiguro is reworking a tradition and introducing ambiguity where nostalgia once lived, Kermode is filling in the gaps here with what is “easily imagine[d]” for him. It is easy to imagine that these characters are “bowing gently,” meaning that they are dressed up in a sort of crude surface Japanese-ness that is exclusively derived from factors outside the novel: Ishiguro’s place of birth, his name.

In a 1985 review of Pictures from the Water Trade: An Englishman in Japan by John David Morley for the LRB, Ishiguro wrote a lede paragraph which has been quoted by them today.

The British and the Japanese may not be particularly alike, but the two races are exceedingly comparable. The British must actually believe this, for why else would they be displaying such a curious desperation to deny it? No doubt, they sense that to look at Japanese culture too closely would threaten a long-cherished complacency about their own. Hence the energy expended on sustaining an image of Japan as a place of fanatical businessmen, of hara-kiri and sci-fi gadgetry. Books, articles and television programmes focus on whatever is most extreme and bizarre in Japanese life; the Japanese people may be viewed as amusing or alarming, expert or devious, but they must above all be seen to be non-human. While they remain non-human, their values and ways will remain safely irrelevant. No wonder the British are so fond of the ‘inscrutability’ of Japanese faces.

Here, Ishiguro gets at the way that the British look at Japan: they don’t realize all that they are failing to see. There is much that English-language critics have failed to see about Ishiguro. In this paragraph, he performs the rather impressive analytical feat of understanding the way his critics see him, defining “inscrutability,” which is one of those racist tropes that is so powerful because it is so menacingly vague.

When a famous writer gets a famous prize, we readers are given an opportunity to reread their books, but also to rethink the thoughts that we have had in the past about those books. It seems to me that Kermode’s way of thinking about Ishiguro has had its time. Of course, different critics take different approaches: One might say that the author’s identity is important to a novel, another might ignore it, or analyze it as part of the author’s oeuvre as a whole.

It’s a personal bias, but I like to read books one at a time. Rereading Never Let Me Go this morning, I found a world composed of parts but, at the same time, unified and self-contained. Ishiguro invites the future into the past in this novel, and in so doing hoists himself into a new vantage point on the present. Go back into Ishiguro over the next few days. It’s worth it. But perhaps don’t bother yourself too much about the critics.