In the winter of 1918, the radical writer and editor Max Eastman wrote to his soon to be ex-wife, Ida Rauh:

I always thought that the avidity with which you could drink up the blood of sacrifice and devotion and still be unsatisfied was truly terrible.… Your conception of what must be given to you seems colossal and hideous, and you rise in my eyes as an unslakable monster of selfishness.

Max wanted his freedom to do his own thing, experience the fullness of life, and follow his heart into the arms of the ravishing young Florence Deshon. If Ida truly loved him, she would set him free. Instead, she was trying to destroy his reputation, but also, almost as inexcusably, trying to lash him back down to domestic life with her.

Eastman includes in his harsh letter to Rauh a much softer letter he has written to their five-year-old son, Daniel. He asks Rauh to give it to Daniel, explaining to her what it says and suggesting to her how to frame it to the boy so that it lands gently. “I tell him that, although I love him and think of him always, I have left him completely to you, because I have hurt you beyond measure, and the only thing that I have that I can give you in compensation is my complete absence from your life and from your love for him.” The act itself is monstrously selfish. Eastman wouldn’t see his son for another 12 years, and would never play much of a role in Daniel’s sad life, which ended in alcoholism and possibly suicide. More stunning, in its way, is the lack of self-awareness. Eastman isn’t just bailing; he’s persuading himself that he’s bailing for his son’s own good. He is pitching it to his ex-wife as a concession to her.

Writing in the second volume of his autobiography, almost 50 years later, Eastman even provides a doctor’s note for it:

Ida, after our parting, had gone into such a state that our physician, Dr. Herman Lorber, advised me not to try to see either her or the baby ‘for a few years at least.’ The rumors of her hostility, and its two-sided exacerbation in some letters we exchanged, had so alienated me that, although I felt waves of sadness about the baby, who was appealingly beautiful, I was not sorry to take the doctor’s advice.

It’s not rare that self-absorbed men and women with visions of their own greatness abandon, neglect, and otherwise damage their children, and Eastman was busy. At the age of 30, in 1913, he was named editor of The Masses, one of the seminal publications of the early twentieth century American left. He transformed the magazine, both radicalizing its socialist politics and infusing them with a sense of literary and artistic élan. Over the next decade or so, he went to Russia to witness first-hand the new Bolshevik order, quickly befriended the leaders of the Soviet Union, produced a masterful translation of Trotsky’s epic History of the Russian Revolution, and mesmerized crowds of Americans with lectures against war and on a dozen other subjects about which he seemed to be effortlessly fluent and captivating.

There is an excellent case to be made that we should remember Eastman for these accomplishments, and others, rather than for the dysfunction of his personal life. He was a major and in most cases salutary figure on the American left for a few decades, and a relatively benign figure on the center and right for another few decades after that. He wrote some wonderful essays, and some good books. He showed genuine political and moral courage as a suffragist, anti-war activist, and anti-Stalinist. Even his truly astonishing degree of promiscuity had its redemptive aspects. He was open about sex and pleasure at a time when such openness was rare and valuable. To those on today’s left, gaining traction once again after many decades on the margins, his biography looks exceptional: a life that intersected with major historical events and impacted a mass audience.

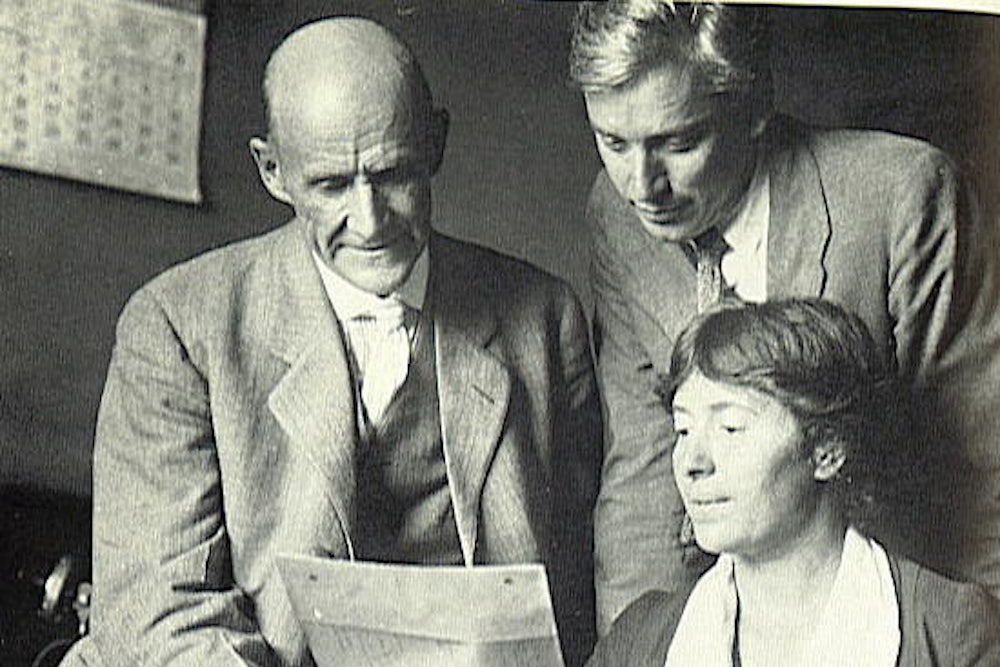

Christoph Irmscher’s Max Eastman: A Life doesn’t make this case. Irmscher, a professor of English at the University of Indiana, clearly knows the politics and history Eastman lived and influenced, though they are not his focus. Born in 1883, in upstate New York, Eastman was raised by two politically progressive, theologically heterodox Protestant ministers. His father Samuel was by far the lesser of the two, his light dim against the fiery sun that was Annis Eastman, a feminist and one of the first women to be ordained in the Congregationalist Church. Annis doted on her three children, particularly Max, and expected great things of them. She also cultivated the kind of home environment that stacked the deck in favor of producing great, or at least complicated and fascinating, people. The Eastman household was a bubbling cauldron of emotional enmeshment, intellectual and sexual sublimation, feminism, progressivism, religious intensity, and interesting people coming and going.

Eastman flourished and suffered in this space. He imbibed early a sense of himself as destined for greatness, and a fierce interest in the world in all its intellectual, spiritual, and physical manifestations. He also was plagued by anxiety, self-doubt, and real and psychosomatic ailments. By the time he arrived in Greenwich Village in 1907, after graduating from Williams College, he had purged himself of most of the outward expressions of his infirmities, and almost instantly cut a charismatic, romantic figure within the cultural and political milieu that would come to be known as the “lyrical left.”

The list of things Eastman did that mattered on the left, from about 1910 to 1940, is staggering. He published John Reed on the Bolshevik Revolution and Randolph Bourne against the war. He smuggled Lenin’s last testament out of Russia, and translated Trotsky into English. He stood up to the U.S. government, and won, when they tried to imprison him for spreading sedition in The Masses. He was one of the earliest American Trotskyists, and then one of the most important skeptics and rejecters of Trotskyism. He was also, in everything he did, an important symbol to many of a certain way of being and acting.

“He came before us then as the fair-haired apostle of the new poetry,” wrote one admirer, “the knight errant of a new and rebellious generation, the man who was making his dreams come true—as poet, as thinker, as editor, as teacher, as psychologist, as philosopher, as a yea-sayer of the joy and adventure of living in the fullest and richest sense of the word.… Life was bursting in all its radiance all around him. For him existence was a fight, a song, a revolution, a poem, an affirmation.”

After breaking with the socialist left, Eastman didn’t cease to be good-looking or charismatic, but the easy alignment between his persona and his politics broke down. He began writing for Reader’s Digest, perhaps the least revolutionary of American publications. He articulated a more conservative politics, in defense of the un-romantic virtues of liberal democracy against the revolutionary claims of socialism. He became a cautious defender of Joseph McCarthy, and a scourge of left-wing and liberal intellectuals whom he believed were wrong on communism and the Soviet Union. “I don’t like McCarthy and I think he’s something of a ham and he is both ignorant and crude,” Eastman wrote to a friend in 1954, “but my objection to him is that he is doing badly a job that has to be done, and that distinguishes me from most of the people whom I call mush-headed liberals, who seem to have even less of the understanding than McCarthy has of the danger to civilization in this totalitarian moment.”

Irmscher in his book describes accurately the relevant encounters, moments, writings, and relationships. He gets the arc, from mama’s boy to neurasthenic student to golden lion of the lyrical left to, finally, idiosyncratic conservative. He competently analyzes the currents of the American left in which Eastman swam, and Eastman’s philosophical differences with intellectual giants like John Dewey, Sigmund Freud, and Leon Trotsky—but he doesn’t seem to care about any of it.

What concerns Irmscher above all is the romantic and sexual life of Max Eastman. After Rauh, Eastman married twice more, in both cases to Eastern European emigrés who adored him, supported him emotionally and often financially, and somewhat grudgingly tolerated the endless procession of younger women Eastman felt compelled to woo and seduce and love and leave. In addition to the actress Deshon, there was the poet Genevieve Taggard, the dancer Lisa Duncan, the painter Ione Robinson. Add to these Nina Smirnova, Vera Zaliasnik, Charmion von Wigand, Scudder Middleton, Florence Southard, Florence Norton, and so many, many (many) more. There was also his sister, the radical writer and feminist Crystal Eastman, with whom he is thought to have had, at the very least, an erotically charged relationship.

Sex, love,

romance, and jealousy are not intrinsically uninteresting material. Great

novels are made of such stuff. But Eastman’s love life, after a while, wasn’t interesting.

It was repetitive and hollow. He liked seducing women. He enjoyed sex. He was

good at it. Every so often, until the end, he would fall desperately in love

with some fresh-faced younger woman. He would write lyrical letters to her and

sometimes even mediocre poems, but he wouldn’t leave Eliena (or later, Yvette)

for her.

When he was

young these affairs could be sexy and glamorous. As he aged, they came to seem

sad and compulsive. “My love, I would give my soul to lie in your arms

tonight,” he wrote to the 24-year-old Florence Deshon in 1917, when he was 34. Twelve

years later, at the age of 46, he was making a version of the same speech to

the 17-year-old painter Ione Robinson, a protégé of his second wife. A decade

later, now 56, he wrote to the 18-year-old Creigh Collins: “I want to sit all

day in the big arm chair with your head warm between my knees, and poetry,

poetry floating around me on your young voice as though thrushes carried its

meaning to my ear.” A year later he impregnated his secretary, the 25-year-old

Florence Norton. When she asked for his help in getting an abortion, “Max

provided a doctor’s address but otherwise became ‘hysterical’ and essentially

abandoned her.” While she was getting a “painful, nauseating abortion,” Eastman

was at his house in Croton-on-Hudson, safely back in the orbit of his wife.

The last few decades of Eastman’s life present a problem to any biographer, since they were substantially less interesting than what had come before. His writing was more predictable and less generous in spirit. He led no magazines, and wasn’t particularly central to those to which he contributed. He wielded some influence in conservative and anti-communist circles, through organizations like the American Committee for Cultural Freedom and magazines like National Review, but he was essential to none of them. His memoirs, Enjoyment of Living in 1948 and Love and Revolution in 1964, were interesting as documents of his age, and for their unusual frankness about sex, but they weren’t great books.

Eastman himself seemed to be aware of the problem. Irmscher suggests that he responded, in part, by doubling down on sex. “His political world shrunken to the size of his country cottage or to a sheet in his typewriter,” writes Irmscher,

Max’s overactive erotic life took on dimensions that would have seemed unmanageable to lesser men. … His correspondence files bulge with letters from women, some of whom have left only their first names to posterity, among them Marie, Lillian, Rada, Creigh, Martha, Amy, and, inevitably, a series of Florences.

Irsmcher is persuasive that Eastman was compensating for a decline in his political influence and a dimming of his myth. The problem, for the biography, is that there is no larger theory of the meaning and significance of Eastman’s life within which to situate this observation. So the book just follows Eastman into his decadence.

It’s easy, as the examples of his womanizing pile up, to lose sight of the reasons why Eastman is the subject not just of this biography but a number of full biographies before it, dozens of chapters in histories and studies of the American left, and thousands of sentences and paragraphs and pages in other books, articles, essays, and documentaries on American political and cultural life in the twentieth century. In April of this year, Routledge re-issued his 1926 book Marx, Lenin and the Science of Revolution. Eastman appears as one of the five featured subjects of Jeremy McCarter’s new group biography Young Radicals: In the War for American Ideals. To the extent that he continues to be read and written about, it’s because of the work that put him at the center of a certain kind of literary and political life for decades. That he was a cad is good to know, but if that were the last or first word about him, there would be no reason to read a word about him almost 50 years after his death.

Irmscher ends Max Eastman: A Life on the sands of Jungle Beach, in Martha’s Vineyard, where Eastman liked to frolic nude. It is a natural end for the book, but it ill serves Eastman’s legacy. It forces us, once again, to dwell too exclusively on his private character, which can’t withstand the scrutiny.

“Among those on the Vineyard who like to shed their clothes,” writes Irmscher,

Max is still remembered, without any equivocation, as a great hero, a god during a time when the island wasn’t yet the playground of the rich and people still loved their bodies. ‘He was a rascal and a rake,’ remembers one longtime Vineyard resident, now in his late seventies. Not only was he always naked, he always had three or four naked women with him. ‘He was a great believer in life. How can you believe in life if you’re all clothed?’ And thus Max Eastman lives on, in the memory of some, a modern God Pan, though more handsome and with soft hands, parting the bushes, stepping out onto the warm sand and into the flowing sun.

Six months after Eastman died, his son Daniel Eastman died, either by heart attack or suicide. As a final revenge on his father, Daniel left his inheritance—some of the land the old man loved most dearly—to a chippy he’d been messing around with. Yvette cleaned up Daniel’s mess, as she had always done for his father, paying the woman some quick cash to give up her claim to the land and go away. This is a natural end to Max Eastman: A Life, but it is much less than Eastman deserves.