President Donald Trump’s speech to the United Nations last week, like much of his public remarks on TV and Twitter, went against the advice of the professionals whom he hired to advise him. Speaking of North Korea, he said, “No nation on Earth has an interest in seeing this band of criminals arm itself with nuclear weapons and missiles. The United States has great strength and patience, but if it is forced to defend itself or its allies, we will have no choice but to totally destroy North Korea. Rocket Man is on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime.” Days later, he tweeted:

Just heard Foreign Minister of North Korea speak at U.N. If he echoes thoughts of Little Rocket Man, they won't be around much longer!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 24, 2017

Trump has a longstanding habit of bestowing childish nicknames on his political enemies, so it’s no surprise that he would refer to North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un as “Little Rocket Man.” But provoking an intemperate ruler who controls a nuclear arsenal is, to say the least, risky—which is why his staff advised against it. According to The Los Angeles Times, “Senior aides to President Trump repeatedly warned him not to deliver a personal attack on North Korea’s leader at the United Nations this week, saying insulting the young despot in such a prominent venue could irreparably escalate tensions and shut off any chance for negotiations to defuse the nuclear crisis.” The article noted that a “detailed CIA psychological profile of Kim” found that he “has a massive ego and reacts harshly and sometimes lethally to insults and perceived slights”—a description which, lethality aside, fits Trump as well.

The ensuing war of words, in which Kim called Trump “a mentally deranged U.S. dotard,” has some foreign policy experts pessimistic. “We are closer to a nuclear exchange than we have been at any time in the world’s history with the single exception of the Cuban missile crisis,” James Stavridis, a retired Navy admiral who teaches at Tufts, told the Times. He put the odds of a conventional war between the U.S. and North Korea at 50 percent and a nuclear conflict at 10 percent. Trump himself continues to entertain the possibility of military action, promising on Tuesday that such an outcome would be “devastating” for North Korea.

President Trump warns of a "devastating" military option as North Korea moves jets https://t.co/UrlNgKgtTH pic.twitter.com/G75dNOhA9a

— CNN Politics (@CNNPolitics) September 26, 2017

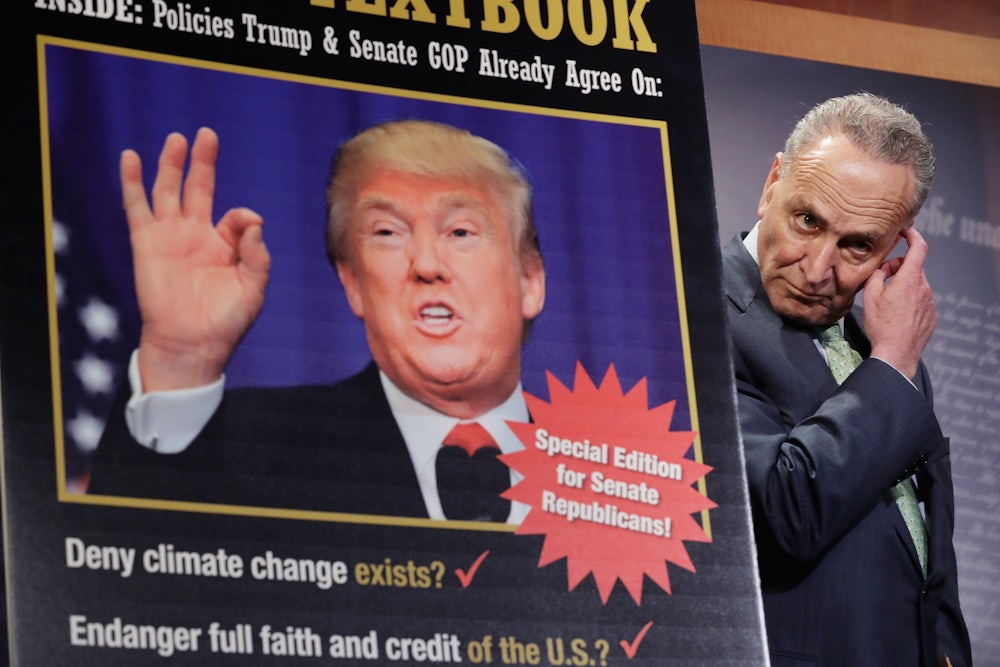

Given the stakes—some 76 million people live on the Korean peninsula, and a nuclear exchange would be unimaginably catastrophic to human life—this escalating crisis should be the subject of a major political debate in America. While “first use” of nuclear weapons has long been a part of U.S. deterrence policy, no president has ever threatened to annihilate another nation over its nuclear program. And yet, while Trump plays a reckless game of chicken, the opposition party has been remarkably muted. “If I were giving the president advice, I would have said avoid using ‘Rocket Man,’” Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader in the Senate, said last week. “We know the leader of North Korea is erratic, to put it kindly. That kind of language I think is risky.” This doesn’t even amount to a correction, let alone a rebuke. In the face of nuclear saber-rattling, Schumer could only muster highly conditional (“if”) and personal (“I think”) advice.

Schumer’s inability to excoriate Trump is not simply a personal failure of the minority leader, but a reflection of the general haplessness of Washington Democrats when it comes to foreign policy. This is not a new problem. The Democratic Party has been deeply splintered on the issue of armed conflict since the Vietnam War, which created a rift between the doves in the base and a sizable cohort of hawks among the party establishment and its conservative ranks. Despite the best efforts of three post-Vietnam Democratic presidents, that rift persists today—but there just might be a way for the party to mend it under Trump.

Prior to the Vietnam War, the Democrats were united in a commitment to liberal internationalism, as practiced by presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, which set the foundations for America’s global role. Liberal internationalism wasn’t just a belief that America had an obligation to uphold the world order, but a commitment to institutions and policies that made it easier for the world’s peoples to trade with each other and form social ties across borders. The vision underlying liberal internationalism is of a peace not just between nation-states, but between their respective citizens.

Early in the Cold War, there was a persistent tension between a desire for greater international fellowship and the desire to counter communism. President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965 intensified that tension, ripping his party apart. “The war wrecked the political coalition that had allowed the party to win seven of the previous nine presidential elections,” historian Michael Cohen wrote at Politico. He acknowledged that the Democratic coalition “was always fragile” and was divided over a number of issues. “But Vietnam was the kill shot—the easily preventable circumstance that at a time of maximum peril for the party created divisions between hawks and doves that tore the party asunder,” he wrote. “Those divisions would manifest themselves four years later, when George McGovern, running on a peace platform ... won the Democratic nomination. Many in the anti-communist wing of the party, particularly in labor, turned its back on him, helping pave the way to an historic landslide re-election for Nixon.”

The divide between hawks and doves hobbled future Democratic presidents. Jimmy Carter tried to solve the problem by appointing leaders from both factions: the dovish Cyrus Vance, his secretary of state, and the hawkish Zbigniew Brzezinski, his national security advisor. The result was an incoherent foreign policy, causing Carter to be depicted by Republicans as weak even when he laid down policies—such as arming the Mujahideen in Afghanistan and restarting the arms race in Europe—that his successor, Ronald Reagan, would maintain. Throughout the 1980s, when they were out of power, the Democrats remained factionalized on foreign policy, broadly disagreeing over issues like the nuclear freeze or the wars in Central America. Democrats controlled the House of Representatives during the whole of Reagan’s term, so all his hawkish policies had to make it through by a coalition that included not just Republicans but a healthy slice of Democrats, mostly Southern conservatives. As Robert Kagan noted in his 1996 book A Twilight Struggle, aid to the Nicaraguan contras was the “defining issue” separating the hawks from the doves. While the hawks feared they would be blamed for letting Central America slide into chaos if they undercut the Republican president, liberals thought, in Kagan’s words, “that Reagan’s policies were immoral.”

The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s and the election of Bill Clinton gave the Democrats a chance for a partial reset. Clinton revived liberal internationalism with military interventions that were justified on humanitarian grounds, notably in the Balkans. Because these wars relied on air power and cruise missiles, there was no human toll on Americans, and so remained uncontroversial with the public at large, although they enraged the anti-war left. Whether Clinton’s version of liberal internationalism could be sustained in a lasting ground war was never tested.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 showed that the same basic division over the Vietnam War remained. The Democratic establishment, including then-senators Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, voted for the war, while much of the Democratic base was skeptical or outright opposed. No wonder a string of eventual insurgent presidential candidates—from Howard Dean to Barack Obama to Bernie Sanders—gained traction in Democratic primaries, if not always victory, by calling attention to their opposition to the war.

Of all the Democratic politicians since Lyndon Johnson, it was Obama who best finessed this divide. His labeling of Iraq as a “dumb war” sent a message that both the hawks and doves could take comfort in. Hawks took Obama’s words to mean that he opposed wars that were badly conceived, but could support justified military interventions. To doves, Obama’s words meant that he saw the folly of all wars. The Nobel Prize that Obama won immediately after the election surely owed much to the hope that he would be a represent a major break from the belligerence of his predecessor. But Obama’s foreign policy pragmatism was apparent in his appointment of Republican realists to high positions, notably Chuck Hagel as secretary of defense and David Petraeus as head of the CIA.

But Obama’s middle road wasn’t just a matter of words. As president, he transformed the global war on terror into a drone war, avoiding American troops on the ground wherever possible. But he also pursued, often in the face of opposition within his own party, diplomatic relations with Cuba and a nuclear agreement with Iran. As Jeffrey Goldberg argued in a 2016 profile in The Atlantic, Obama’s vision was guided by the conviction that America had over-reached in its commitments and that its power was more limited than his immediate predecessor believed. “If Obama ever questioned whether America really is the world’s one indispensable nation, he no longer does so,” Goldberg wrote. “But he is the rare president who seems at times to resent indispensability, rather than embrace it.” If the Democrats remained divided between hawks and doves, Obama embodied both sides of the contradiction: a reluctant hawk, one who felt America had to marshal its resources and work with allies whenever possible. Obama disavowed the much mocked phrase “lead from behind,” which an administration official used during the Libyan crisis of 2011. But it still stands as encapsulation of the Obama administration’s effort to engage with the world while avoiding grandstanding and displays of dominance.

The question facing Democrats is, Do they have someone who can follow in Obama’s footsteps? The politician making the best case to carry the mantle, despite being ideologically well to the left of Obama, is Senator Bernie Sanders.

Sanders’s recent foreign policy speech, notably in its strong defense of the Iran nuclear deal, was a careful attempt to claim Obama’s legacy by arguing for a liberal internationalist approach of alliance-building to solving the world’s problems. The central theme of the speech was the need to re-conceptualize foreign policy not just as a matter of military policy. “Here is the bottom line: In my view, the United States must seek partnerships not just between governments, but between peoples,” Sanders argued. “A sensible and effective foreign policy recognizes that our safety and welfare is bound up with the safety and welfare of others around the world.”

This is a revival of a core component of liberal internationalism that was dominant from the 1940s to the 1960s: the emphasis on interaction between citizens across the globe, which led to the Truman administration’s development of foreign aid as a diplomatic tool and the Kennedy administration’s creation of the Peace Corps. After the divisions of Vietnam, this approach fell into relative disfavor, seen as too naive by those who favored military solutions and too complicit in American foreign policy by many in civic society.

In Sanders’s speech, we can see the outlines of his attempt to bridge the gap between Democratic hawks and doves. He fully acknowledges the hawk’s case about the dangers of ISIS and of nuclear proliferation in Iran and North Korea. But he wants follow in Obama’s footsteps by engaging diplomatically with other powers to curtail proliferation. Also like Obama, Sanders sees problems like climate change as part of foreign policy. But he also goes farther than Obama, presenting economic inequality as an international problem. On this, he’s vague, although it’s certainly possible to imagine trade agreements that strengthen international taxing powers and labor rights.

At a time when the Democratic base—not to mention a consequential percentage of Republicans—are skeptical of military action, Democratic politicians with presidential aspirations would do well to follow Sanders’s approach. Trump’s rhetoric frightens many Americans across the political spectrum, so many voters will support a foreign policy alternative to the hawkish establishment. As we saw in the years following the Iraq war vote, electoral fortune is likely to favor the candidates who are brave enough to chart a new path.