For two decades, the Pentagon operated under a simple doctrine: We must always be able to fight two wars at once. But in 2009, the Pentagon started to rethink its strategy. Since 9/11, the nature of world conflict had changed; the military needed to be able to fight more than two wars, and to be prepared for unconventional threats. “We have learned through painful experience that the wars we fight are seldom the wars that we planned,” Defense Secretary Robert Gates told reporters at the time.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is likely facing a similar realization. Three unique, major hurricanes have hit three distinct, major metropolitan areas—and the damage was far more extensive than had been planned for. “This is the FEMA equivalent of the Pentagon’s two-war doctrine,” said Jeff Schlegelmilch, the deputy director for the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. “I’m not aware of any time in FEMA’s history where they’ve had to handle three major disasters at once.” The young agency, formed in 1979, has had to deal with a sharp increase in the number of billion-dollar disasters in the last decade. But this year will likely be the most expensive yet. “There’s no doubt about that,” Schlegelmilch said. “I really honestly think this is going to be the most costly year on record for disasters.”

FEMA, as a rule, does not plan for the worst-case scenario when it comes to natural disasters. According to Schlegelmilch, the amount of money in the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), the pot of money allocated for declared disasters, is determined based on the average annual cost of past catastrophes. A few weeks before Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, FEMA Administrator Brock Long wrote that the $3.8 billion left in the DRF was “sufficient to support the needs of disaster survivors and communities through the remainder of the fiscal year”—but only “absent a new catastrophic disaster.” There have been three new, near-unprecedented catastrophic disasters since then, and they are projected to have stunning price tags: Anywhere from $65 billion to $190 billion for Harvey, $50 billion to $100 billion for Irma, and $40 to $80 billion for Maria. (Hurricane Katrina’s cost was estimated at $160 billion in 2017 dollars.)

To deal with that, FEMA needs Congress to allocate emergency supplemental funding. Congress approved a $22 billion aid package as part of President Donald Trump’s government funding deal with Democrats, but that’s just “a down payment,” Schlegelmilch said. A FEMA spokesperson said that as of Monday, there was only $5 billion left in the DRF for major disasters; an additional $6.7 billion will become available on October 1. But that’s not nearly enough, and over the next few months, Congress will be asked for many billions more.

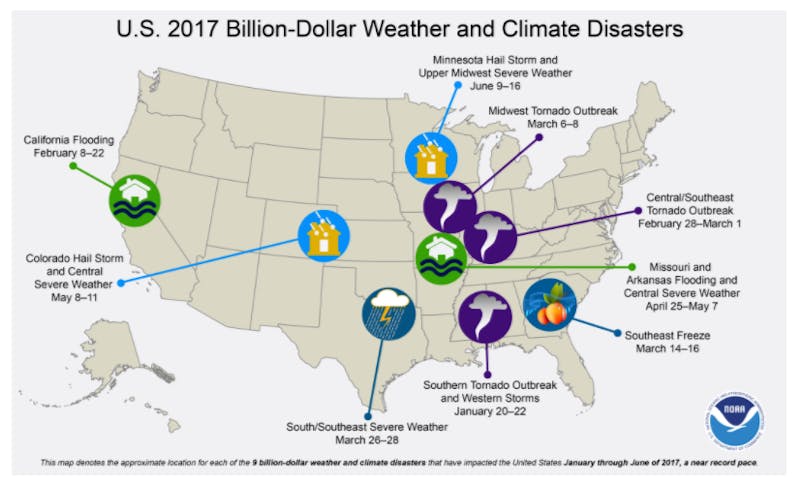

The biggest short-term mistake Congress could make would be to delay approval of necessary funding; to allow American cities and citizens to suffer in the name of partisan bickering. But the biggest long-term mistake would be to consider this year a fluke. “We’re seeing these emergency supplementals more and more as the cost of disasters increase,” Schlegelmilch said. “Whereas they used to be sporadic, we’re seeing them almost on a yearly basis.” According to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. on average experienced about five disasters costing more than $1 billion every year from 1980 to 2016. But from 2012 to 2016, the annual number of billion-dollar disasters ballooned to about 10. This year will add to that average: Before the three major hurricanes, the U.S. had already seen nine natural disasters that cost more than $1 billion—and there’s still more than a month left of hurricane season.

As these disasters increase in number, so will their intensity as the world warms. Flooding events—the most costly type of natural disaster—are expected to worsen over time, because a warmer atmosphere is able to hold more moisture and therefore release more rainfall during storms. A warmer atmosphere and ocean can cause more powerful hurricanes, and extended heatwaves and droughts will cause more frequent wildfires.

There’s not much FEMA can do with this information right now. The agency must respond to the disasters in front of them, and quickly. But Congress should learn from this experience that the current model for natural-disaster preparation is deeply flawed. We can no longer plan for the average cost, and continue to throw money at catastrophes after they occur. “There’s been rumblings in the emergency management community for a while about how sustainable this is,” Schlegelmilch said. He cited the National Flood Insurance Program, which gives government assistance to homeowners who live in flood-prone areas if their homes are destroyed. “There’s a lot of questions about whether these programs just underwrite risky behavior,” he said. “There is a growing consensus that the way that we fund relief is unsustainable because it doesn’t incentivize preparedness.”

There are a number of proposed solutions floating around. Michael D. Brown, the former FEMA administrator under President George W. Bush, suggests injecting a huge amount of money into the Disaster Relief Fund via the federal budget, so the agency doesn’t need to scramble to ask Congress for help. “If we built up a reserve of $100 billion, we’d actually have time to figure out the best way to rebuild,” he said. Schlegelmilch and others say the government should take better advantage of the calm between storms, and provide incentives for local governments to prepare buildings and roadways for major events. “The real question is, why are we spending so much on relief to begin with?” Schlegelmilch said. “Why aren’t we spending on preparation and resilience?” Conservatives like Brown also suggest eliminating the National Flood Insurance Program. “I’m not saying you shouldn’t live in a flood zone,” Brown said. “I’m just saying other taxpayers shouldn’t subsidize your choice.”

Over the next three months, Congress will have to fund the federal government (again), including FEMA’s budget and the Disaster Relief Fund. It will weigh whether to reauthorize the National Flood Insurance Program. And it will decide how much more emergency funding to provide for hurricane relief. The debate over these bills will raise long-term questions about what the nation’s disaster response should look like. The answer is to reform FEMA’s outdated disaster doctrine.