Even the best novelists are rarely congratulated on the quality of their observations about contemporary life. Realism is all well and good, but, it seems, there can be too much of it. There is something a little vulgar about writing a novel that is too close to the present, too concerned with current events, too eager to critique technological advancements. Imagine, if you will, a novel that was actually, directly, about Donald Trump. Too on the nose, we reviewers would sniff. Too much like an internet think piece.

Jennifer Egan has invariably escaped such critiques. Her last three novels have all, to some extent, presented commentaries on technology and its discontents. Look at Me (2001) explored the psychosis inherent in the reality TV era’s obsession with public image, while The Keep (2006) kicked off its refashioning of the Gothic with the loss of a protagonist’s portable satellite dish. And, if you believe the reviewers, the entire achievement of her last book, A Visit From the Goon Squad (2010), lay in its perfect rendering of the fractured conditions of modern existence.

Goon Squad, a decentralized, nonlinear book in which an entire chapter took the form of a PowerPoint presentation, distilled the very essence of a culture that—we know now, we didn’t know then—was about to find a dreadful new level of meaning in the term “disintegration.” Marrying the splintered format of the novel to the intelligence of her narration and the gracefulness of her prose, Egan achieved something of a paradox: She elegantly presented the inelegant, the confusing, the vulgar, and the cheap. She has a way of sending up the flimsier aspects of modern life without seeming glib. Her novels take on the disconnection of online connectedness, the mismatch of fame and meaning without—a problem that seems to plague your average, isolated novelist—sounding totally disconnected from or condescending toward the phenomenon being described. Goon Squad includes, for instance, a fake celebrity profile that at once lampoons the form and pays tribute to the slavering a journalist must do in order to write one. At the outset, the starlet is described as “human bonsai,” about as good a metaphor for female celebrity as I’ve ever read. By the end of the interview, she’s stabbed the journalist with a Swiss army knife.

So it comes as a surprise that Egan’s new novel, Manhattan Beach, contains not one tiny measure of any of the things described above. It is set mostly in the 1940s, before any of these problems of fractured meaning seemed as striking or urgent as they do now. It begins at the beginning, with a girl headed to the Atlantic Ocean, and ends at the end, with the same girl headed towards the Pacific. Whereas her other novels invited comparisons to the postmodernists—say Don DeLillo—here we’re closer to the realm of lyrical realism, something more like a novel by Colm Tóibín that quietly works through Egan’s particular concerns. While there are breaks and loop-backs in its narrative timeline, Egan has put together a rather uncharacteristically ordinary book.

Manhattan Beach’s Anna Kerrigan is twelve when we meet her, and we are told, right off, that she comes from a deprived background: In the novel’s opening pages, she can’t help but covet the doll of a rich little girl she has just met in a home steps away from the titular beach. She is accompanying her father on a mission to this house for reasons that aren’t revealed to us. But it is made clear that Eddie Kerrigan is involved in shady business and that, as the Depression slides towards World War II, his ability to meet his obligations is slipping. Anna has a disabled sister, Lydia, whom Eddie can barely stand to look at. Lydia cannot speak or care for herself and her illness inspires revulsion in him. When she hypersalivates, he feels “a flash of fury, even a wish to smack her, followed by a convulsion of guilt.”

A couple of chapters in, Eddie does what men in romantic novels always do when they face an emotional challenge they can’t easily resolve: He flees the scene. Anna and her mother are left to care for Lydia, largely on their own, laboring under the presumption that Eddie is dead, and surviving on money periodically doled out by Eddie’s wayward spinster sister. When World War II arrives, 19-year-old Anna finds gainful employment in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. We get an introduction to the training procedures for new hires—“six weeks of instruction”—and we are also immediately informed that Anna is special, singled out by her boss for special responsibilities in the Yard. It’s not clear why she might be so.

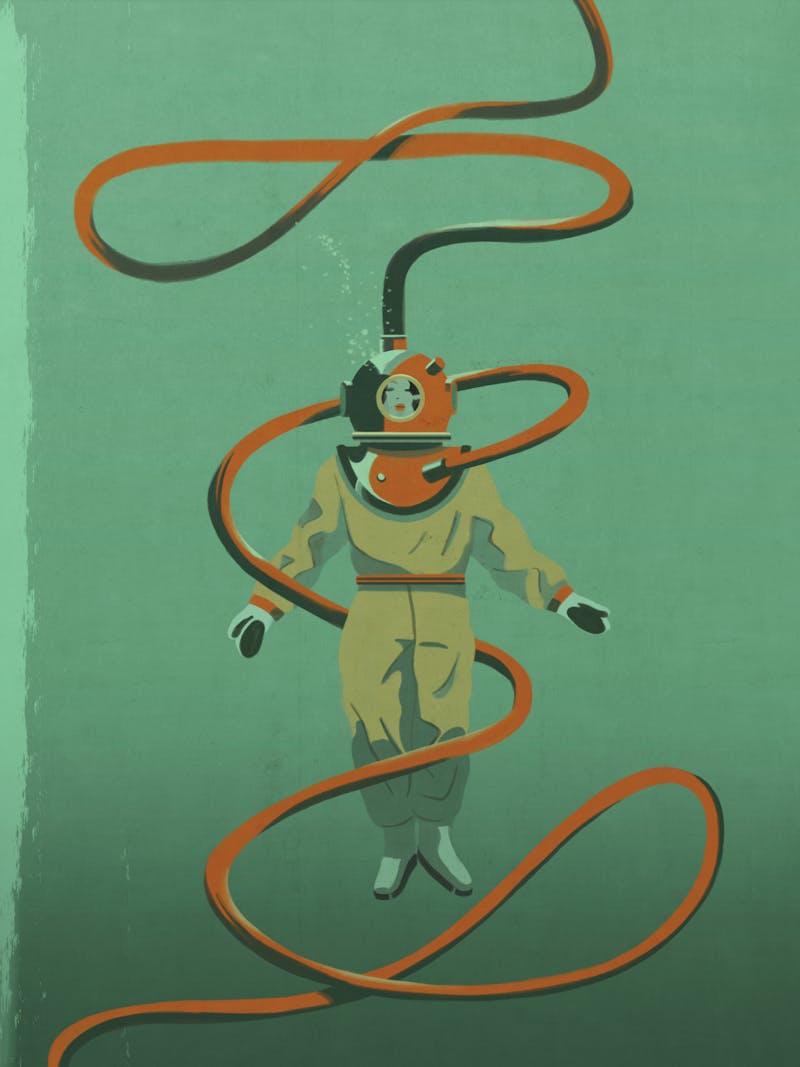

In these early portions of the book, Egan finds much pleasure in looking around the Yard itself. She presents the setting as a fantastical place, as well-ordered as clockwork, and seems to delight in depicting all the moving parts of this world. When Anna goes to lunch, Egan observes how she “synchronized her wristwatch with the large wall clock.” The bike Anna borrows from a friend is not just a bike, but a spur to her imagination: “Motion performed alchemy on her surroundings, transforming them from a disjointed array of scenes into a symphonic machine she could soar through invisibly as a seagull.” Anna eventually finds her way onto a diving team, and the intricacies of early deep-sea diving form a central part of the book. As she fits into the heavy “dress” that allows her to breathe hundreds of feet underwater, she relishes the qualities of the equipment, finding transcendence even in the gloves, “her hands delivering her to a purely tactile realm that seemed to exist outside the rest of her life.”

Egan has always been something of a sensualist, an unusual characteristic in a novelist who is also frequently deemed “cerebral.” Her lush use of language has often distinguished her from DeLillo or Pynchon, as well as other writers who share her concerns and interests. Her characters have a habit of getting lost in their feelings, as when the protagonist of her first novel, The Invisible Circus, becomes sexually enthralled by her dead sister’s boyfriend. Even when the experience is not pleasurable, Egan often describes it as though it were. The car crash that opens Look at Me is like a fairground ride, “a slow loop through space like being on the Tilt-A-Whirl.”

In Manhattan Beach, there’s pleasure—but it comes less often from the visceral experience of the characters than from their experience of the technology they are using. For a while, it works. It’s relatively easy for us to marvel over the brass bolts of a 1940s diving dress or the wheels of an ancient Schwinn. We have none of the qualms about those objects that we might have, say, about a smartphone. There is something wondrous about the technologies that the characters in Manhattan Beach have at their disposal. They don’t seem to carry any real costs.

That, of course, is the rub. The novel so elegantly represents the past that it doesn’t have any sense of friction or edge. The social conditions are scarcely fleshed out, with little sense of how race and class shape the characters and their wartime work. Gender is clearer: Unmarried but sexually active, Anna inevitably gets pregnant. She has had to fight to get her spot on the diving squad. But we never learn the real purpose of the diving operation at the Navy Yard. No one worries much about rations. And we hear little about the war or anyone actually fighting at the front. Egan’s polish can come off as the kind of gloss Hollywood likes to layer on a historical film, removing layers of dirt and grime and, above all, moral complication.

Yet Egan doesn’t suffer the ailment that typically afflicts literary novelists who venture into history: She isn’t nostalgic. Nor is she vague, not exactly. You will leave Manhattan Beach knowing a lot about diving equipment. One gets the impression that Egan found herself with piles upon piles of research. The acknowledgments explain that she has been researching the divers and the Navy Yard since at least 2004—which would mean she started this project before her last two novels were published—and then had difficulty knowing how to turn all that information into fiction. Research can be a boon to a novelist—there are more things in heaven and Earth than can be dreamt of in a single writer’s philosophy—or it can become a hindrance, a thick layer of algae that weighs down the storytelling. Egan’s wartime divers, for all their breathing apparatus, threaten to sink Manhattan Beach.

After we’ve learned everything there is to know about diving, the focus shifts to Eddie Kerrigan. His disappearance gives Anna something to long for, an explanation to seek. Gradually, predictably, she finds herself caught up with the same gangsters who ensnared Eddie. One dashing man, who goes by the 1940s-noir name Dexter Styles, may be able to tell Anna what happened. And if the climax of her entanglement with Styles feels a little neatly assembled—the diving dress is involved, and a boat anchored off Staten Island in the middle of the night—it comes as a relief to see that all that stuff we learned about the equipment has a narrative purpose, not just an expositional one. A lesser writer would have frozen up.

But it is barely clear what any of this is about, in a way unusual for an Egan novel. She likes to have a big, overarching purpose going, some governing metaphor, even if it’s executed in fragments and dazzling bits of narrative fireworks. Much of her work sustains itself not so much on the kind of cinematic structure and imagery we’re given here, as on the quality of her insights into the conditions of modern life. And Egan seems to have known she wanted or needed to do something like that here. In 2011, when Goon Squad won the Pulitzer and Egan was at the top of the literary world, she gave an interview to The Guardian about her next novel, clearly Manhattan Beach. “One big question I have with the book is how to write a historical novel in a way that’s more playful than just setting it in the past,” she said. “That doesn’t work for me. I’m going to have to mix it up a little more.”

Here we have no playfulness, only the deep and the ocean. An epigraph from Herman Melville opens the book: “Yes, as every one knows, meditation and water are wedded for ever.” The deep sea is indeed very quiet, an oasis from all the activity on the surface, a place where the normal rules of movement, and even of breathing, don’t apply. The slow, meditative pace of Manhattan Beach was perhaps meant to mimic this, the entire book a vacation from the frantic everyday onslaught of disconnected information that Egan has usually been so eager to chronicle. But maybe that’s it: Maybe Egan, in this book, needed a break too.