For a long time in American politics, you could pretty well guess how someone would vote by their income. Poor people generally supported Democrats; rich people voted Republican. This was true even among whites: In every presidential election since at least 1948, wealthy whites have been notably more Republican than the rest of the white electorate. And throughout the twentieth century, poor whites identified much more strongly with the Democrats than other whites. For decades, a good rule of thumb was: The greener your bank account, the redder your vote.

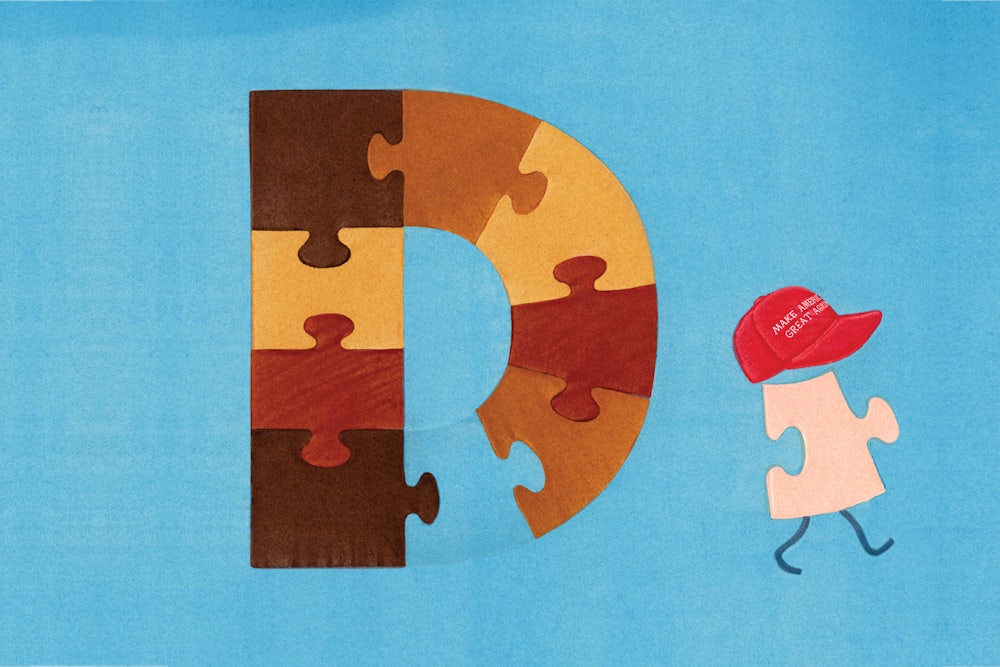

Then came Donald Trump, and the equation shifted. In last year’s election, according to an analysis by political scientist Tom Wood, 61 percent of the poorest whites—those in the bottom third of income distribution—voted for Trump. By contrast, in the top 4 percent of income distribution, just 42 percent of whites supported Trump. Among whites, millionaires decisively rejected their fellow millionaire, while blue-collar voters embraced him.

What drove the vote in 2016 was not income, but identity. Trump won by appealing directly to the cultural anxieties of downscale whites: He told them he’d do something about the immigrants who were stealing their jobs and the Muslims who were plotting to blow us up. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, appeared to dismiss working-class whites as “deplorables,” and put on a convention that was a paean to multiculturalism. As both parties made appeals based more on race and culture than on class and economic inequality, almost 10 percent of voters who cast their ballots for Barack Obama in 2012 decided to abandon the Democrats. The famed blue wall that ran through the Rust Belt came crashing down, and Trump walked over the rubble straight into the Oval Office.

Since the election, Clinton has often been blamed for focusing too much on “identity politics.” But the suggestion that Democrats return to the populist economic rhetoric that made them heroes of the working class ignores the current political reality. The cultural forces that swayed the election in favor of Trump are likely to remain. What doomed Clinton, in the end, was not that she appealed to racial and ethnic minorities, but that she paid them little more than lip service. As Democrats attempt to move forward, they must come to grips with the fact that many of the working-class whites who abandoned the party are likely gone for good. The sooner they accept that reality, the sooner they can win with the coalition they have.

From 1932 to 1964, Democrats were America’s majority party. They consistently held the White House and Congress, with few interruptions, because they were the party of the working class, and millions of Americans directly benefited from the social welfare programs they stood for.

To maintain this majority, Democrats had to hold together a coalition of Northern liberals and Southern conservatives who disagreed vehemently on civil rights. As long as racial equality took a back seat to New Deal economic programs, the coalition held. But once the moral urgency of the civil rights movement made desegregation inevitable, the coalition split apart. And after Ronald Reagan won the Oval Office in 1980 by appealing to blue-collar whites, Republicans found they could pry the working class away from Democrats by emphasizing culture and race over economics. Over the next quarter-century, the only times Democrats won the White House—in 1992 and 1996—came when Bill Clinton exploited his status as a white Southerner to neutralize the GOP’s emphasis on cultural issues.

Democrats were further hurt by the dramatic decline of labor unions. For decades, organized labor had helped the white working class see themselves as the white working class. But without unions to identify and defend their economic interests, the white working class became the white working class. As Democrats came to rely less and less on union voters, and more and more on affluent urban cosmopolitans, their rhetoric and policies increasingly came to reflect the interests of a more highly educated and diverse constituency. By 2008, this coalition was big enough to help elect Barack Hussein Obama, even though 59 percent of working-class whites voted Republican. But with a black man in the White House and immigration on the rise, the Tea Party and Trump were able to fan the flames of racial and cultural resentment. In the end, Obama’s election helped accelerate what has been a long, slow shift in the political identity of blue-collar whites. The fact that the change has occurred steadily, and over a period of many decades, only makes it all the more difficult to reverse.

How, then, should Democrats proceed? Democrats have traditionally fared better when they emphasize class over culture, encouraging white workers to vote their wallets. Broadly speaking, this can be achieved by de-emphasizing racial and cultural issues, or by re-emphasizing economic issues. In the current political landscape, however, neither approach is likely to work.

The first option, to de-emphasize race and culture, may simply be impossible at this point. Trump is waging an aggressive effort to crack down on immigrants and undercut civil rights laws, while offering unabashed support to white supremacists. Advising Democrats to tone down cultural issues feels a bit like telling a kid who’s being punched in the face by a bully that he should try to be a little less violent.

The second strategy, to re-emphasize economic issues, also faces a significant hurdle. In theory, if Democrats came out with a big, bold economic agenda, they might be able to convince blue-collar whites that Democrats are still the party of the working class. But at this point, it may be hard to regain the trust of those voters, given how solidly they have come to see Trump as their savior. And it’s hard to imagine what that bold economic agenda would even look like, given how deeply Democrats have come to depend on a class of very wealthy donors who would like to stay very wealthy.

So: If neither of these options seems feasible, can Democrats win by playing on the turf of culture and identity? The short answer is yes. But to do so, they’ll have to overcome two obstacles: a geography problem and a turnout problem.

Let’s start with the geography problem. Thanks to our antiquated electoral system, areas of the country that are culturally and racially conservative enjoy outsize influence. At the presidential level, Democrats have won the popular vote in six of the last seven elections—yet a Republican still entered the White House after two of those defeats, thanks to the way the Electoral College favors rural and suburban voters at the expense of city dwellers. At the congressional level, the increasing concentration of Democrats in a relatively small number of urban districts—combined with aggressive GOP gerrymandering—has enabled Republicans to hold a majority in the House for 18 of the last 24 years. If Democrats get back into power, they should fix their geography problem by passing electoral reforms to render gerrymandering impractical and force candidates to appeal to a broader range of voters.

If Democrats were serious about getting out the vote, they would begin building on-the-ground organizations today, reaching deep into low-turnout communities. But that would require them to rethink their entire party apparatus, which prioritizes fund-raising at the expense of everything else. Would-be candidates in competitive districts are told that their first task is to raise millions of dollars from rich people so they can pay consultants and pollsters to produce ads and do social-media targeting. There’s a lot more money to be made in buying TV time, it would seem, than in building meaningful connections to voters.But Democrats can’t fix their geography problem until they solve their turnout problem. It’s a matter of math: The GOP’s core constituencies (older, wealthier, churchgoing) get to the polls at consistently higher rates than core Democratic constituencies (younger, poorer, secular). In last year’s election, just 49 percent of millennials voted, compared to 69 percent of baby boomers and 70 percent of the “greatest generation.” Hispanics voted at a lower rate than whites, and black voter turnout dropped for the first time in two decades. If every generation and race had voted at the same rate, Democrats would have won in a landslide.

But campaign infrastructure alone isn’t enough. To motivate their core constituents, Democrats also need to embrace a message that speaks more directly to their concerns. A truly progressive economic and civil rights agenda would engage the constituencies that Democrats need most—not working-class whites, but low-income minorities. Donald Trump won by appealing to the cultural anxieties of blue-collar whites. By the same token, Democrats can win by appealing more explicitly to the hopes, fears, and dreams of their broad coalition, and giving them a reason to turn out on Election Day.

As America becomes more and more diverse, issues of race and culture will continue to dominate the political discourse. The good news is that Democrats, for perhaps the first time in modern history, can actually turn that reality to their advantage. The bad news is that, even if they succeed, the discord and hatred that the GOP is using to mobilize its base will continue to divide the country for decades to come. The Republican emphasis on race and culture poses a solvable problem for Democrats. It poses a more difficult problem for democracy.