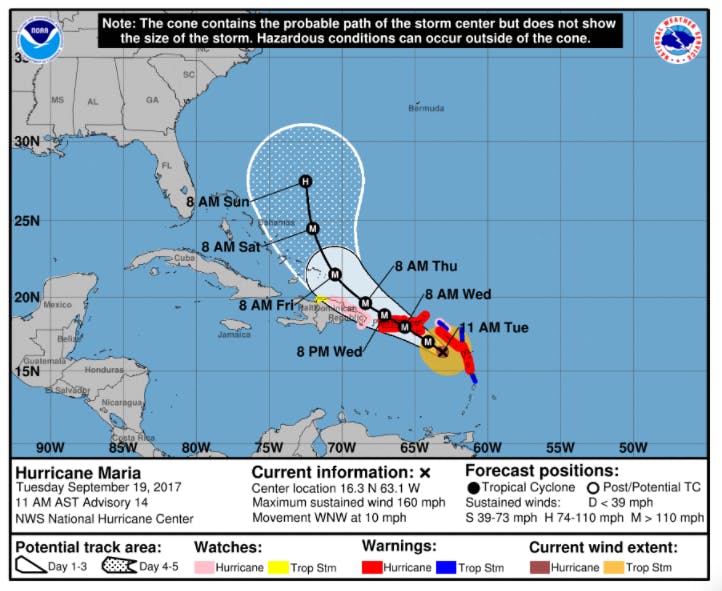

Last week, Puerto Rico was lucky. This week, it’s not. The majority of the U.S. territory was spared the worst from Hurricane Irma, the Category 4 storm that devastated the lower Florida Keys and Caribbean islands including St. Martin and Barbuda. But now Hurricane Maria, a Category 5 monster with 165 mph winds, is headed straight for the heart of the island; every meteorological prediction shows the storm pummeling Puerto Rico. Rain is already falling, and the eye is expected to hit as early as Tuesday evening.

“[Maria] will essentially devastate most of the island,” Puerto Rican Gov. Ricardo Rosselló said in a Monday interview with USA Today. Most of the nation’s 3.4 million residents will lose power, structures will be destroyed, and neighborhoods will be flooded. There will be food and supply shortages. People will die. And the recovery will be especially difficult due to Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy and the $1 billion in damage wrought by Irma. But on top of all this, Maria could worsen the many environmental calamities that already exist on the island, posing even greater threats to public health—particularly in low-income areas—as boricuas struggle to recover from the storm.

In some ways, Puerto Rico will face familiar environmental threats caused by major hurricanes, but they’ll be compounded by the island’s financial and environmental woes. For instance, wastewater pumping systems failed in Texas and Florida after Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, causing major sewage spills. The same will likely happen in Puerto Rico, where most pumping stations run on electric power, but may be much worse due to the island’s “degraded and unsafe” electricity system. The local energy authority has already said it could take up to four months to restore power, likely resulting in prolonged sewage releases.

Also like Florida and Texas, Puerto Rico has Superfund sites—23, to be exact—that risk contaminating soil and groundwater, one of which is among the most complicated, expensive Superfund sites in the U.S. For six decades, the military used the Puerto Rican island of Vieques as a bomb-test site, resulting in widespread contamination of three quarters of the small island. Many claim this contamination has caused the heightened cancer rates among the 9,000 people who live there. Unexploded bombs, bullets, and projectiles are all over Vieques, according to Judith Enck, the former EPA administrator for Region 2, which covers Puerto Rico. “I am concerned that the ones on the land will wash into the sea,” she said.

Puerto Rico also has its own unique environmental concerns. Adriana Gonzales, a Sierra Club environmental justice organizer based in San Juan, is particularly worried about coal ash in southern Puerto Rico. In the southern coastal town of Guayama, she said, a five-story pile of coal ash sits uncovered next to a low-income and minority community of 45,000 people. Owned by Applied Energy Systems (AES), the pile of ash—which contains heavy metals like arsenic, mercury, and chromium—has long been the source of complaints about “fugitive dust,” or ash that gets swept off the pile on windy days. Maria’s landfall will be a very windy day. “It will be a catastrophic thing for these communities to be showered with ash,” Gonzales said. She noted that AES was ordered by the Puerto Rican government to secure this toxic pile before Irma made landfall there earlier this month, but it’s still unclear if adequate steps have been taken. AES did not return a request for comment.

The Guayama pile is not the only site where coal ash threatens human health. For years, AES also dumped thousands of tons of coal ash in southern Puerto Rico landfills. That’s generally accepted practice, but it’s different in Puerto Rico because almost all of its landfills are overflowing due to the financial crisis. That’s a recipe for disaster given the 25 inches of rain expected to fall from Maria; according to the EPA, coal ash most frequently poses human health risks when it gets wet, allowing toxins to leach from the ash and percolate into soil or drinking water.

Puerto Ricans also have to worry about landslides. Hurricane Hugo, a Category 4 storm that hit the island in 1989, triggered more than 400 landslides in the eastern mountains. Landslides pose not only an immediate risk to human life, but a prolonged risk to water if contaminated soil reaches surface water. A USGS study on Puerto Rican landslides warned as much: “Because most of the soil eroded by landsliding is delivered directly to river channels, fluvial sediment loads can remain high for many months following large storms,” the study reads. “For example, a single landslide that occurred during Hurricane Hortense in the Río Icacos watershed in El Yunque introduced a mass of soil into the river that is equivalent to the average annual sediment yield for an entire year.”

Hopefully, Maria won’t exacerbate any of these problems. But the multi-pronged environmental threat Maria poses to Puerto Rico should serve as a wake-up call. The island is, after all, a U.S. territory—something the EPA has been accused of forgetting when it comes to the region’s landfills and coal ash disposal. Natural disasters are not preventable, but environmental contamination is.