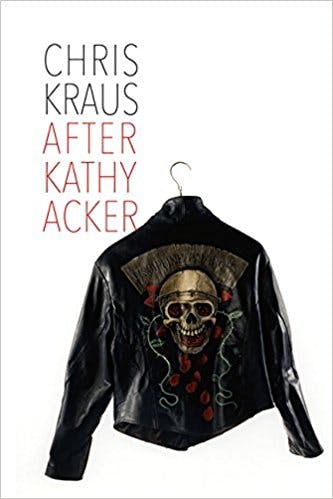

Kathy Acker knew a lot of people. In her new biography After Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus doesn’t exactly say that she had a lot of friends: just that, by the time she died, she’d “known thousands of people.” Acker was a countercultural hero who hybridized elements of punk, literary postmodernism, feminism, and critical theory in her public identity and in her literary works. Take the very title of her 1984 novel Blood and Guts in High School: it’s gross, it’s cool, it’s funny. As befits a woman who interbred identities in her writing, Acker flowed through scenes, making the acquaintance of “poets and bikers, leather dykes, tattooists, philosophers, astrologers, renowned artists and writers, bodybuilders, psychics, promoters, and editors.”

In emphasizing Acker’s social (and sexual) promiscuity but staying silent on the question of actual friendship, Kraus delivers one of the backhanded compliments that characterize this biography. The book’s overall sensibility is that of a tense friendship, even a resentful one. Kraus does not clarify her personal relationship to her subject, and so the question of their relation becomes a void into which her tone rushes. Acker certainly doesn’t come off as an easy person to like. Kraus elevates this unlikeability to be the defining feature of her person.

Kathy Acker was born in 1947 and died of cancer at fifty. Kraus opens her book with the bizarre pageant of Acker’s ash scattering ceremony in Fort Funston, California. The urn was carried by Matias Viegener, Acker’s executor and the editor of a posthumous collection of emails between Acker and MacKenzie Wark, I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995-1996. As the group scrambled down a dune towards the sea, something baroque and awful happened:

… Frank Molinaro, the odd one out, the one nobody in the group liked, rushed up and grabbed the vase from Viegener’s hands. The astrologer ran toward the sea tossing handfuls of ash and bone while he proclaimed—“You’re free, Kathy! You’re finally free!”—before Viegener and Scholder wrested it back. It was bitter cold, and no matter how hard they tried, no one could toss the ashes into the waves, because the wind blew them back.

From this unromantic end Kraus pivots to Acker as a twenty-three year old living in Washington Heights in 1971 (she grew up on 57th Street). This period of her life was formative, in part because she spent a lot of it performing in a live sex show in Times Square with a then-boyfriend. When Acker shaved her head, they worked it into the act as a Joan of Arc concept. By this time she was no longer with Bob Acker, her first husband, whom she’d met when she was a sophomore at Brandeis. Before that, she was a smart, unpopular student at The Lenox School on the upper East side.

Acker’s road to literary success and out of it was winding, and Kraus spares her reader none of the details. Her first public reading was May 7, 1971 at the St Mark’s Poetry Project open mike. She began writing the six-part serial The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, the work which would make her name as an experimental stylist, in 1972. She went to San Diego. She suffered from pelvic inflammatory disease. She wrote Rip-Off Red, Girl Detective. She recorded The Blue Tape, a movie in which she went down on Alan Sondheim on camera. She married again, briefly. She went to London. She wrote Blood and Guts in High School. She became famous. She wrote Don Quixote. She got good reviews and bad reviews. She became sick, she became convinced by faith healers that she was well, and she finally became dead in Mexico.

Those are some details, thrown together haphazardly: it isn’t the same as a life. To evoke a life you have to fill bits in with the flavor of the person, how it felt to be with her in a room. But over the course of this densely researched and detailed book, Kraus fills the spaces between these details with inferences which border on cruel. At one point, Kraus quotes her own researcher’s correspondence with a classmate of Acker’s from school. She reproduces a series of texts from this person, which form a vicious poem of remembrance:

I read the high [sic] School

book. Wow. She was really

off the wall. Drugs?

Insanity?

…Why is anybody writing about

her, except as

a clinical study?...

…

We shld talk again when

you can tell me more.

Right now, I have to watch

Wolf hall!

This is a very lovely set of lines, and it certainly demonstrates the fact that many people find Kathy Acker’s writing debauched and inane. But is information about how people thought Kathy Acker was nuts important to a book that is nominally about Kathy Acker herself?

It seems accurate that Kathy Acker was kind of a pill. But that begs a further question: does it matter? I’m not so sure that it does, at least not enough to justify the attention Kraus pays to Acker’s supposed failures of character. Acker has been compared a lot to William Burroughs. It’s tempting to extend the comparison and to wonder whether Kraus didn’t feel that she had to treat Acker in a way that actively worked against the hero worship that characterizes some artists’ cults of personality. Fans of Burroughs don’t seem to think that it matters that Burroughs was a total bastard. Kraus seems to think that in the case of Acker, it should matter.

The book contains more than one anecdote describing what a bad and unwelcome houseguest Kathy Acker was. She is portrayed as sycophantic to some, dismissive and patronizing to others. Kraus describes Acker’s letters to Bernadette Mayer, for instance, as written in “painful and almost tone-deaf eagerness.” She slept with everybody’s boyfriends.

In places, Kraus shows how Acker’s self-centeredness connects to her literary appeal. Acker’s biological father abandoned her mother in pregnancy, an unelaborated fact which haunts her oeuvre. Kraus quotes some lines from Acker’s Portrait of an Eye on the subject:

My mother tells me my “father” isn’t my real father: my real father left her when she was three months pregnant and wanted nothing to do with me, ever. This husband has adopted me. That’s all she tells me.

In this work, Kraus observes, we get the daughter’s perspective and nobody else’s. But this extreme first-person voice is by the same token exceptional: “perhaps the greatest strength and weakness in all of Acker’s writing lies in its exclusion of all viewpoints except for that of the narrator.”

“Acker had no shortage of female contemporary writers throughout the 1970s,” Kraus says. She cites “Jayne Anne Phillips, Margaret Atwood, Anna Beattie, Alice Munro, Janet Frame, and dozens of others” who “published semiautobiographical novels with strong female narrators.” Unlike any of those women, however, Acker disdained “naturalistically-described situations.” Those women wrote books in which “the presence of their narrators was wholly relational.” Unlike these writers, Acker was not well respected. But then again, “they never sought or attained the iconic status of Great Writer as Countercultural Hero that Acker desperately craved. Until she achieved it, no woman had.”

In the same breath as describing Acker’s greatest strength, Kraus calls it a weakness. In the moment of paying tribute to Acker’s extraordinary access to countercultural literary heroism, she disdains her with the words “desperately craved.” It is as if Kraus has identified the good-in-bad principle of Acker’s identity—which we might otherwise call “antihero”—and subjected it to analysis on moral terms. So, we have literary appreciation and a sort of character condemnation working against each other in the same analytical moment.

Reading this ambivalent book was confusing because I like Kathy Acker’s writing a lot, in part because of the things that made her a bad person to know. I like Kathy Acker because of the density of her first-person voice. She is never likeable but she is fully and without anxiety herself (though her other anxieties proliferate). People with very dense experiences of their subjectivity often are callous and selfish and unpleasant. By the same token, I want to read writing by such people. Consider these lines from Great Expectations (1982):

I have no idea how to begin to forgive someone much less my mother. I have no idea where to begin: repression’s impossible because it’s stupid and I’m a materialist.

These two sentences are difficult to interpret and the first time I read them I realized that I had never been given sentences about mothers to read that were deliberately uninterpretable. Instead of interpretation, Acker here gives us persona and statement. These lines read like lyrics by a self-aggrandizing old man who deals in generalities. This never happens—is never allowed—in writing by daughters about mothers.

Chris Kraus was married for a long time to Sylvère Lotringer, whom you may recall as the husband in Kraus’s highly influential work of autofiction, I Love Dick. Sylvère Lotringer was also a friend and sexual partner of Kathy Acker. There’s no suggestion of resentment on this count—but it’s an important fact because it demonstrates how extraordinarily close Acker and Kraus were in literary historical terms, and how enormous a void is left in After Kathy Acker by the unnaming of that relation.

This large and mysterious gap in the biography is filled necessarily by the emotional tenor of Kraus’s writing, which expresses distaste and disdain for Acker as a woman and as a writer. It’s only a guess, but it may be that Kraus’s social proximity to Acker (leaving out the issue of literary proximity, for it’s a slightly different one) may have suggested to her that Acker’s character flaws were more important than they are to her readers. Still, for all its rigorous accounting of Acker’s personal failures, one might mostly describe the book’s affect as “blank.” “In London, she played chess with Salman Rushdie,” Kraus writes, with no indication of whether chess or Salman Rushdie are good or bad.

But there is one section of the book in which Kraus’s tone heightens rather than reduces Acker’s dignity—the section on her death. In her final summer, Kraus writes, Acker “got sicker. She couldn’t eat or digest food or walk more than a few blocks without tiring.” Next, and with no transitional sentence, Kraus records the affirmations that Acker wrote for herself:

“I affirm that every day is a day of wonder. I affirm that though I don’t see it, I have more money than I need, I earn more than I need, I live in a house w/ room for all my books next to where I can walk in the woods, I am healthy I love my work, my money & my books are in the hands of the right people & I have time for my work, every day I open more & more to vision,” she wrote in her notebook.

Over the course of After Kathy Acker, Kraus has been inside her diaries, burrowed inside her friendships, psychoanalyzed and praised a little and recorded much. But only with Acker’s death does the detail of Kraus’s research match the purpose for which it is intended: remembering with honor the dead writer.

Biography-writing is a very tricky form, and no reader could fault the dedication with which Kraus has chased down the archival and human remains of Kathy Acker on earth. As an Acker fan, I inhaled this book. But as the last pages turned, the biography’s lingering flavor was one of bitterness. Whether that was done in the name of the truth or in the name of dislike, we can’t know.