There is no such institution as the American Creative Nonfiction Hall of Fame, but were some frivolous people to bring it into existence, I have to imagine that John McPhee would be on the first ballot. In over 50 years of writing (exceedingly) long features for the New Yorker, and over 40 teaching future writers and editors at Princeton, McPhee has shaped the craft like few others, with epic, sprawling stories such as “Looking for a Ship,” “A Fleet of One,” and “Oranges.” For the past five years his work for the New Yorker has turned inward, to his own process. Eight of those essays on writing are collected in Draft No. 4, McPhee’s 29th book, but his first on doing what he does.

If the book is any indication of the kind of instruction students at Princeton receive, they’re a lucky bunch indeed. McPhee’s knowledge of, experience with, and command over narrative nonfiction structure is masterful. In the first two sections he lays out story diagrams that start simple but get so complicated they could fluster an offensive coordinator. Nonfiction structure should be invisible to the reader, McPhee writes, but under his observation it emerges huge and immediate, like a ghost armada appearing all of the sudden close to shore. He exposes the artistry in creative nonfiction, and what the readers see isn’t the freewheeling New Journalism of Hunter S. Thompson or Tom Wolfe. It isn’t full of high-speed action or obvious liberties with the truth. McPhee’s isn’t action painting; if he is painting at all, his brand of composition reminds me most of forgery: He doesn’t futilely attempt to recreate reality, but to mold something so full and alive that it would be hard to start a long and complicated disentangling from the actual.

Inspired by the preponderance of natural cycles in the Arctic, McPhee shapes a story about Alaska around a circle. The first half of the arc will take place linearly, progressing from the beginning in the straightforward humanly experienced direction of time. Halfway through, the narrative flashes back to an earlier point, which we follow to the end, which is also the beginning. McPhee’s concern is less a desire to ape the movement of the moon, and more that the trip’s most dramatic event (a grizzly bear encounter) occurs earlier than it would ideally, which is “about three-fifths of the way along, a natural place for a high moment in any dramatic structure.” McPhee makes even the limited power of narrative sound awesome: “You’re a nonfiction writer. You can’t move that bear around like a king’s pawn or a queen’s bishop. But you can, to an important and effective extent, arrange a structure that is completely faithful to fact.” You can’t move bears, but you can move time, and that’s just as good.

Draft No. 4 contains a carefully balanced ratio of directly instructive writing advice, behind-the-scenes views on McPhee’s greatest hits, and war stories from the golden age of post-WWII American magazine publishing. This is near the bullseye of what you’d hope for from an octogenarian doyen, and it’s a pleasure to read. Any writer or editor could learn something from McPhee, as many famous and successful ones already have. In the essay “Frame of Reference,” he advises against borrowing vividness from famous names: “If you say someone looks like Tom Cruise—and you let it go at that—you are asking Tom Cruise to do your writing for you.” Any obscure reference tightens the writer’s audience, almost always for the worse. Though McPhee does end the section with the story of an elegant exception, a fittingly exceptional line of writing gifted to a few readers who would receive it.

McPhee’s celeb stories are charming: Jackie Gleason is in turns ornery and apologetic, Richard Burton takes a shine to the young reporter. His fellow New Yorker contributor Woody Allen gets his first humor piece back with an editor’s note that the essay contained too many funny lines. But when McPhee starts getting into the labor conditions he has experienced during his career, we move solidly into “must have been nice” territory. In his essay on “editors and publisher,” McPhee readily admits he was “very lucky to come into The New Yorker when I did.” He never received assignments—except from charming and eccentric strangers—and his conflicts with higher-ups revolved around individual peculiarities and minute, detailed questions of professional concern. The bosses are loose with time, attention, discretion, and money. When he asks editor William Shawn, “How can you afford to use so much time and go into so many things in such detail with just one writer when this whole enterprise is yours to keep together?” The editor answers, “It takes as long as it takes.”

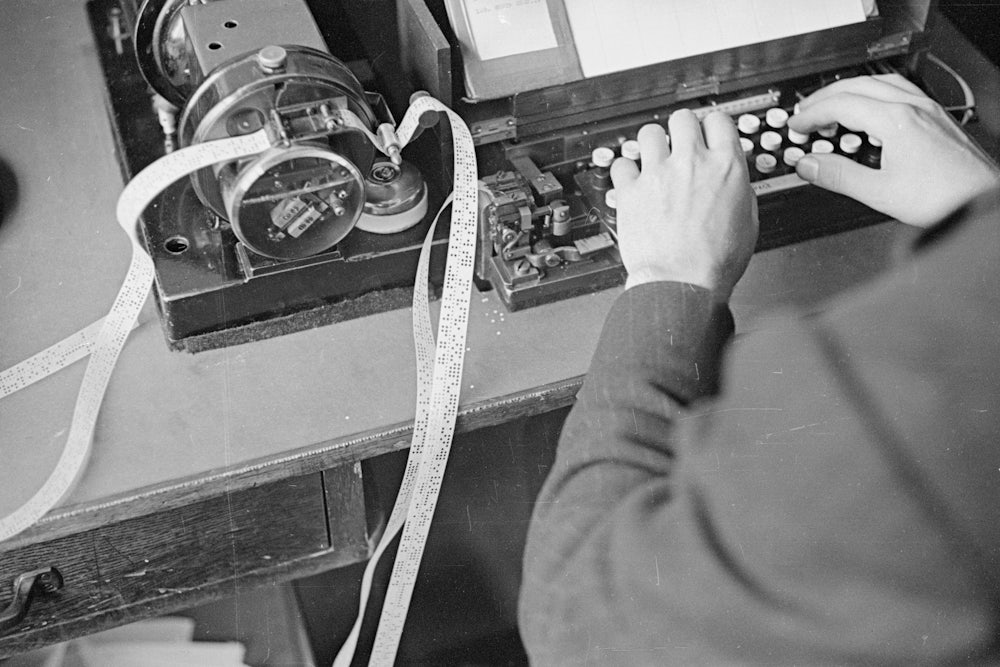

I feel incredibly lucky to make a living as a writer, but today’s luck is very different than McPhee’s in the ‘60s. In his New Yorker contributor biography, McPhee is credited with bylines on “over 100 pieces.” I laughed out loud when I read it; it’s not uncommon today for even established writers to publish that many pieces a year. These stories are not 40,000-word epic sagas about colorful men and their long journeys by truck, boat, or sled; they are shorter, on the Internet, with smaller budgets, and they are more likely to be written by women. (“Time’s writers were men, and the researcher/fact-checkers were women. They were expert,” he writes of his time at the magazine.) McPhee flashes back to 1966, when he spent nearly two weeks lying on a picnic table “staring up into branches and leaves” thinking about how to start an article. Of his process, McPhee writes,

The daily journalist has to go out, get the story, and write it in one day, a feat that leaves me breathless and beggars all comparison with the time involved in my projects—four months in the New York City Greenmarkets, three weeks with a flying game warden, two weeks with a Nevada brand inspector, months at a time across three years of trips to Alaska. I have no technique for asking questions. I just stay there and fade away as I watch people do what they do.

The market’s role in journalism and publishing has changed both a lot, almost entirely for the worse as far as McPhee’s heirs could be concerned. McPhee’s stories about negotiating with Roger W. Straus Jr. at the publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux sans agent should come with a big bold warning that says “Do not attempt this in 2017.” FSG, once an eccentric independent house, is now a corporate subsidiary of Macmillan. Straus was there to support McPhee, implying (in McPhee’s recollection) that they’d even publish his bad books. When the New Yorker hit a rough spot, Straus offered McPhee a parachute package of five book deals. Given their professional context, his intricate structural diagrams start to look like runes of a bygone profession.

There are few writers emerging today who could convince FSG to publish a book of essays seven-eighths of which is already available on a single tagged page at the New Yorker. I would recommend Draft No. 4 to writers and anyone interested in writing, but no one should use it as a professional guide uncritically or they’re liable to starve. If you’re a young writer trying to make it, I’d suggest reading the essays online and save the $26 cover price of the book. The New Yorker only gives you six free pieces a month, but those who seek out this collection will probably already know that.