The momentum is all on the Democrats’ side. Donald Trump is historically unpopular. The progressive base is angry and activated, with semi-regular mass protests testifying to the seriousness of their opposition. It is widely expected that Democrats will make gains in the 2018 midterms, and that Trump himself will face an extremely tough re-election battle in 2020. And yet that momentum has not translated into the currency that matters most in politics: cold, hard cash.

The Democratic National Committee has a fundraising problem. In July, the DNC raised $3.8 million, lagging far behind its Republican counterpart, which raised $10.2 million in the same month. This is the worst haul for any month since January 2009, when Barack Obama was first inaugurated. Overall, during the first half of 2017, the RNC has pummeled the DNC, raising $75.4 million to the Democrats’ $38.2 million.

The main difference is that Republicans have a sitting president who has started fundraising for his re-election campaign early, and who can drive small-dollar donations. “An incumbent president can be a powerful fundraising tool,” Michael Beckel of Issue One told the New Republic. “That’s something that Democrats don’t have right now.” But the Democrats are also presiding over a fractured and scattered fundraising regime, which suggests that, beyond an ambient opposition to Trump, they are divided in terms of both tactics and priorities.

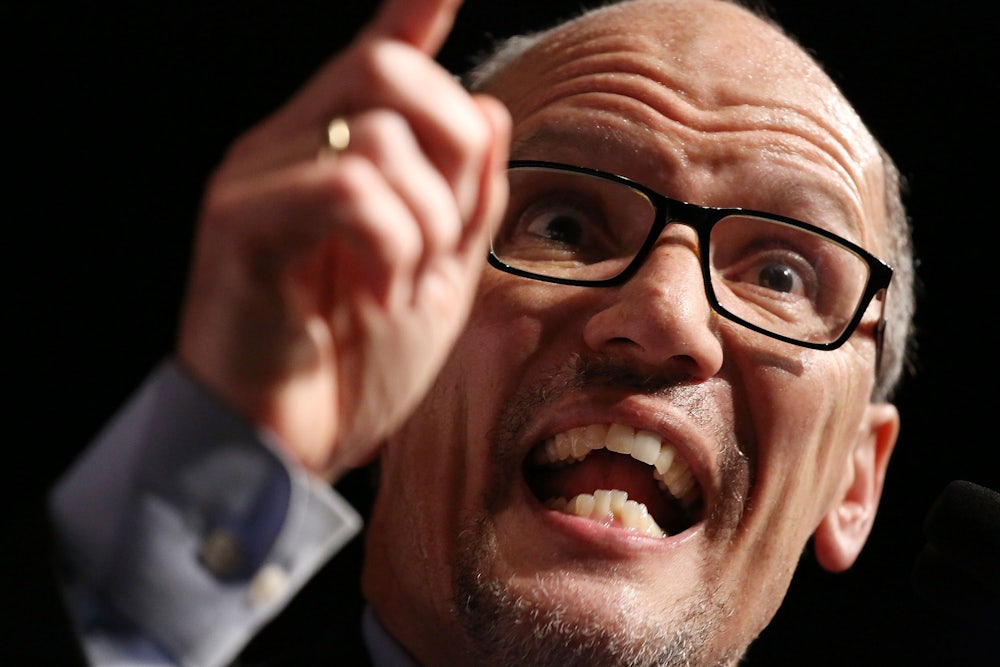

There is no denying that the DNC has struggled to capitalize on progressive energy. It is sorely missing Obama, who proved to be an especially talented fundraiser over his two terms. The DNC’s new chair, Tom Perez, is also in the midst of rebuilding the committee’s staff and revamping its strategy after the debacle of the 2016 election. Still, other groups have had more success.

In July, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which works to elect Democrats to the House, outraised its Republican counterpart by $6.3 million to $3.8 million, undoubtedly fueled by the upcoming midterms. In 2017, the two parties’ congressional committees are roughly neck-in-neck overall. Meanwhile, grassroots donors drove individual Democratic campaigns like that of Montana’s Rob Quist and Georgia’s Jon Ossoff. After Trump announced his first Muslim ban in January, donations to the ACLU surged, with the group raking in $24 million online over a single weekend, almost seven times than what they raised in the entirety of 2015.

As Ben Kamisar and Amie Parnes wrote in The Hill about the DNC, “The lagging fundraising has frustrated some Democrats, who see Trump’s sinking favorability and stalled agenda and the ongoing Russia probes and wonder why the national party can’t translate that grassroots energy into donations.”

Some, like Ed Kilgore, have argued that it’s too early to freak out over the fundraising disparity, because the overall levels of cash swimming around are similar and the Republicans have more seats to defend in 2018 and beyond. But the DNC’s gap in small dollar donations—$33 million versus $21 million in favor of the RNC—is concerning. As Michael Whitney, Bernie Sanders’s digital fundraising manager during the 2016 primary, wrote in Politico, “This isn’t just about money. Small-dollar donors are an important measure of how much grassroots enthusiasm a campaign or organization has.”

Whitney blames the DNC’s email strategy, which can seem transactional and spammy, rather than exhorting followers to contribute to a lasting political movement, a la Sanders’s primary campaign. Polling also shows that a majority of voters believe that the Democratic Party doesn’t stand for much other than opposing Trump.

Finally, the highly publicized battle in February between Perez and Keith Ellison to lead the DNC solidified the impression that the establishment, fresh off the heels of its most devastating loss in decades, was wary of loosening its grip on the party. With many options to choose from, including formerly fringe groups like the Democratic Socialists of America, progressive donors are choosing to invest their money in other political outlets.

Exacerbating this sense of atomization is the fact that the party’s two most famous figures aren’t on the same page. Obama and Hillary Clinton are throwing their respective weight behind their own political groups, rather than behind traditional party organs.

As reported in Politico last October, Obama’s main political priority post-election is to support the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, a new group launched in January and chaired by Eric Holder, Obama’s former attorney general. The NDRC’s focus is on rolling back a decade’s worth of gerrymandering by the Republicans that has decimated the Democratic Party at the local level. While Obama has largely stayed out of the political fray, he did return for one night to host a private fundraiser for the NDRC in July. According to Politico, the NDRC has raised $10.8 million in the first half of the year, much of it from mega-donors like Donald Sussman and Fred Eychaner.

Clinton launched Onward Together in May, a political nonprofit whose stated goal is to help support grassroots groups opposed to Trump. But it remains an open question just what kind of groups her organization will back. Meanwhile, we’ve seen a proliferation of Clinton-esque groups like New Democracy and Win the Future, which seek to steer the party toward the center.

“Obama and Clinton are both high-profile Democrats and neither have been helping the DNC raise much money,” Beckel said. There is a finite amount of resources, and it’s possible that Obama and Clinton are pulling the deep donor networks that they have cultivated away from the party itself. (Obama, however, has reportedly been privately advising Tom Perez.) Their favored projects only add to an already fragmented ecosystem, putting the DNC at an even bigger comparative disadvantage than its Republican counterpart since it also has to compete with two of the party’s biggest stars.

On the one hand, the fragmentation of the party could be considered a healthy development. It might force the DNC to reach out to a broader electorate, rather than relying on a few large donors. On the other, fragmentation also allows private interests to prevail, a troubling development because outside spending groups are typically less accountable and transparent than parties themselves, which have to disclose contributions of over $200 and have a cap on individual donation amounts.

A group like Onward Together, which is a 501(c)(4), does not have to disclose its donors. Such organizations can do so voluntarily, as Organizing for Action and Sanders’s Our Revolution have done, but Onward Together has not, prompting the Campaign Legal Center to write in May that “Clinton’s group is following a dangerous path that could further open the floodgates to even more unaccountable money in politics.” NDRC, which has a similar mission to the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, is part federal PAC, part 501(c)(3), and part 501(c)(4).

At the root of these differences in the fundraising world lies a host of ideological divisions that Democrats have yet to resolve. Are they the party of transparency and small donors? Or will they continue to rely on wealthy individuals and corporations, under the cover of loose campaign finance laws that the party opposes in principle? Are they committed to representing the diversity of opinion on the left? Or is their main function to funnel money to candidates of a particular mold? Do they want to build a movement? Or are they hoping that plain anti-Trump sentiment will obviate the need for one? It may be too early to freak out about the fundraising gap between Republicans and Democrats, but all signs point to a party that remains in disarray.