Bobby Corrigan is the rat master. Some call him the rat czar. To others, he is simply a rodentologist, or as NBC recently described him, “one of the nation’s leading experts on rats.” Call him what you want; he is mostly alarmed. “I travel all over the world with this animal, and the amount of complaints and feedback and questions I hear right now are all, ‘We’ve never seen rats in the city like this before,” he said. “They’re all expressing the same concern: Our rat problem is worse than ever.”

Most cities know rat woes well. Washington, D.C., for instance, has burned through countless plans to stymie its longstanding “rat problem” or “rodent crisis,” in which disease-ridden critters are not only growing in number but ballooning to the size of human infants.

What they don’t know is how this all will end. Houston, Texas, is seeing a rat spike this year, and so is New York City. In Chicago, rodent complaints for the early part of the summer have increased about 9 percent from last year, forcing city officials to start sprinkling the streets with rat birth control. Philadelphia and Boston were recently ranked the two cities with the most rat sightings in the country. And it’s not just this year; as USA Today reported last year, major cities saw spikes in rodent-related business from 2013 to 2015. Calls to Orkin, the pest control service, were reportedly “up 61 percent in Chicago; 67 percent in Boston; 174 percent in San Francisco; 129 percent in New York City; and 57 percent in Washington, D.C.”

It’s no surprise that rats thrive in cities, where humans provide an abundance of food and shelter. But experts now agree that the weather is playing a role in these recent increases. Extreme summer heat and this past winter’s mild temperatures have created urban rat utopias.

“The reason the rats are so bad now, we believe, is because of the warm winters,” said Gerard Brown, program manager of the Rodent and Vector Control Division of the D.C. Department of Health, at a 2016 rat summit.

Rat pro Corrigan agrees. “Breeding usually slows down during the winter months,” he said. But with shorter, warmer winters becoming more common—2016 was America’s warmest winter on record—rats are experiencing a baby boom. “They have an edge of squeezing out one more litter, one more half litter,” Corrigan said.

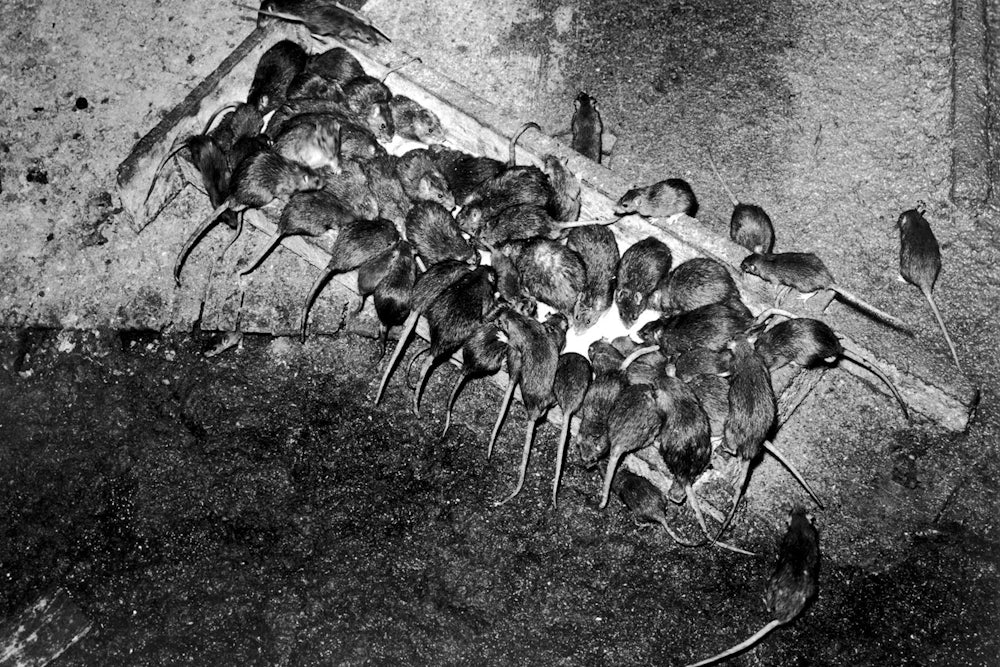

One more litter or half litter makes a serious difference when a population boom is not only a nuisance, but a public health and economic crisis. Rats breed like rabbits; as this alarming Rentokil graphic shows, two rats in an ideal environment can turn into 482 million rats over a period of three years. Urban rats caused $19 billion worth of economic damage in the year 2000, partially due to the fact that they eat away at buildings and other infrastructure. Imagine how much they’re costing now.

What’s more, every new litter increases the risk of a rodent-borne disease. A 2014 Columbia University study showed that New York City’s rats carry diseases like E. coli, salmonella, and Seoul hantavirus, which “can cause Ebolalike hemorrhagic fever,” according to the Washington Post. Rats also carry the rare bacterial disease known as leptospirosis, which recently killed one person and sickened two in the Bronx.

Clearly, the coming ratpocalypse is no longer a city-centric problem. It is threatening the health of millions across the country, costing billions of dollars, and is being fueled by global climate change that the U.S. primarily created. And yet cities—which are expected to hold 70 percent of the world’s population by 2050—are largely dealing with their rodent crises on their own. Why isn’t the federal government stepping in?

The federal government wasn’t always silent on rats. From 1969 to 1982, the Center for Disease Control awarded cities grants under what was known as the Urban Rat Control program, championed by then-President Lyndon Johnson. The program started small, servicing only 19 communities across the country, but eventually grew to serve 65 communities with an annual budget of $13 million, which was matched by state and local governments. While the program did experience some hiccups, it was widely considered successful. Quoting the CDC, the Associated Press reported in 1982: “As a result of the efforts, 7.7 million people now live in rat-free, environmentally improved neighborhoods.”

But President Ronald Reagan eliminated the program, saying the rat problem should be dealt with by individual states. That irked former CDC Director of Environmental Health William Houk, who told United Press International at the time that the program was “one of the more worthwhile projects of the federal government.” Reagan’s decision to cut it, Houk said, “is a classic example of the government doing something with the people instead of for them.”

Rat-plagued cities are now left to their own devices. And they’re not exactly doing a great job. In part, that’s because rats are elusive. As Linda Poon wrote this year for CityLab, “no one really knows how many rats there are. Not in New York City, nor Washington, D.C., nor Chicago—all three of which rank among the most rodent-infested cities in the U.S.” Rats in these urban areas depend on humans for food and shelter, meaning their environment only improves as more and more humans cram into cities with every passing year. And as researchers noted in the Journal of Urban Ecology this year, rats rapidly evolve to resist poisons, the most commonly known form of extermination.

Still, the biggest roadblock, Corrigan said, is that rat eradication programs are just plain underfunded. “It’s been my experience watching cities that people are not willing to pay what it takes to get rid of all the rats affecting a property or a building,” he said. And even when cities are willing to pony up, it’s still not enough. Even in the best-case scenario, New York City’s staggeringly large $32 million program to kill rodents would reduce rat populations in the city’s most infested areas only by 70 percent.

Federal funding could help to close the gap. Officials at the CDC may not be paying much attention now, but they should be, if only because the public health cost of rat infestations has never been fully studied. It’s hard to quantify just how much money rats are costing health systems, Corrigan said, because most people sickened by rats have flu-like symptoms, and many don’t know they’ve been exposed to a rat.

Public health is not just a local issue, and neither is climate change. Researchers admit that it’s extremely difficult to study rats, but many are confident that if temperatures continue to rise, rat populations—and the problems that come with them—will continue to grow. “I personally feel there is a connection with climate change, just because of logic and the biology of rats’ reproductive cycle,” Corrigan said. “Global climate change fits into this discussion in some measurement. How much, I’m just not sure.”

But the Trump administration doesn’t need to accept that climate change will make rodent infestations worse to step in and save the cities from their rats. As the administration has eliminated federal programs to fight climate change, cities have stepped up, aggressively funding their own efforts to slow carbon dioxide emissions. Cities are already fighting battles that shouldn’t be only theirs to fight. The least the federal government could do is chip in for some rat control.

Maybe the best way to get Trump’s attention and sell him on reviving the Urban Rat Control grant program is to stress that there is glory to be had, and for relatively cheap. “Rats are very incredible, wildly intelligent mammals, and human beings keep going around trying to exterminate [them] as if it’s the opposite,” Corrigan said. “These cities are up against one of the most incredible mammals on the planet, which only stand to increase in number.” For a mere $13 million (plus inflation), Trump could stop the ratpocalypse before it begins.