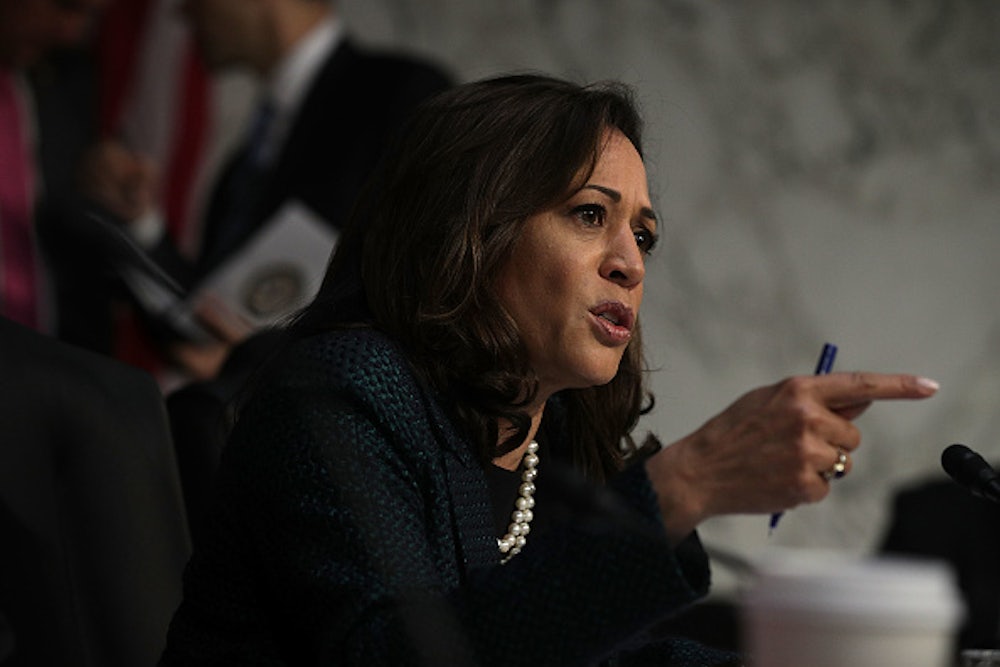

After eight years with a black man in the White House, the left still has no idea how to talk about African American politicians. Nowhere is this clearer than the ongoing conversation around Kamala Harris of California, the first Indian-American and only the second black woman to be elected to the Senate. Harris is the Berkeley-bred daughter of immigrants from India and Jamaica. The former California attorney general grew up attending civil rights rallies, and she recently dominated headlines for her tough questioning during the Senate Intelligence Committee’s hearings on Donald Trump’s campaign’s alleged ties to Russia. And her rising star status has set her up as a focal point of the the latest battle between the center and the left.

As Mic’s Andrew Joyce reported in July, Harris has a “Bernieland problem.” Joyce homed in on the hypocrisy of leftists who criticize Harris for her allegedly lukewarm support for progressive causes, quoting a Bernie Sanders organizer who had called on Harris to support universal health care, free college, a federal $15 hour minimum wage, criminal justice reform, and the expansion of social security programs. Harris, it turns out, had already announced her support for all five of those proposals.

Joyce was hinting at a broader criticism often leveled at Harris’s detractors—that racism and sexism, not real policy differences, are the driving forces behind the left’s animosity toward Harris.

Three days later, writing in The Week, Ryan Cooper tried to make the case that policy, in fact, is at the heart of the debate. Don’t worry, he assured us in a column titled “Why leftists don’t trust Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Deval Patrick,” it has nothing to do with bigotry—the left objects to these three possible presidential contenders because they would fail a progressive purity test. Cooper pointed to Harris’s controversial track record as a prosecutor; to Patrick’s ties to Bain Capital, the much maligned private equity firm Mitt Romney founded in 1984; and to Booker’s close relationship with Wall Street and “the despised donor class.”

It was easy to recognize the one thing Harris, Booker, and Patrick all had in common: their race. Big hitters on the center left—from Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, to former Clinton adviser Peter Daou—joined a chorus of voices dismissing the critiques leveled at these three black politicians as bigoted vitriol. “So odd,” Tanden wrote on Twitter, “that these folks have it in for Kamala Harris and Cory Booker….hhhhmmm.” Leftists fired back, pointing to their support for black politicians like Keith Ellison and Nina Turner as proof positive of their tolerance, the political Twitterverse’s equivalent of “I have a black friend.”

No side, in other words, has come out looking good. And on a deeper level, the debate about Harris lays bare the myopic way in which liberals engage with blackness. On the one hand, black politicians, as symbols of the Democratic commitment to diversity, are portrayed as infallible, never to be questioned or critiqued. On the other, they are held to standards of perfection that white politicians rarely have to meet. Lost between these poles are black politicians themselves, who have instead been reduced to pawns in a fight between left and center.

In Democratic politics, the cachet of black women has never been higher. Hours after Trump won the presidency last fall, #Michelle2020 started trending nationwide. After enduring a years-long ethics investigation, Representative Maxine Waters underwent a full-blown rehabilitation when she refused to attend Trump’s inauguration, telling MSNBC in no uncertain terms, “I don’t honor him. I don’t respect him, and I don’t want to be involved with him.” Democrats collectively fawned over her, and “Auntie Maxine” is now fodder for the viral news cycle, inspiring gospel remixes and headlines like “Maxine Waters is Back and She’s Not Here to Play.” And when Kamala Harris was interrupted as she interrogated Jeff Sessions during a Senate hearing, she “became the new face of ‘Nevertheless, she persisted.’”

It’s as though Democrats have agreed that supporting members of their most loyal voting bloc with hyperbolic headlines and adoring tweets is the same as actually addressing their concerns. But in the end, these testimonials are a creepy form of fetishization that denies black women their full humanity, particularly when they fail to account for their very real failings.

The centrist reaction to Cooper’s article in The Week was more of the same. Tanden and others batted down Cooper’s concerns without a second thought—because Harris, like Obama and Waters before her, was apparently above reproach. And yet there are many valid critiques that can be leveled at Harris. Most, rightfully, stem from her tenure as California’s top cop, where she gained a reputation for talking the progressive talk but not following through “in a vigorous way,” as Think Progress put it.

She defended California’s death penalty law when it was challenged in federal courts; she declined to take a public position on two state ballot initiatives that would have reformed the sentencing practices for common drug and theft crimes that disportionately keep young black men behind bars; she declined to join in other states’ efforts to remove marijuana from the DEA’s list of most dangerous substances; and, perhaps most damningly, she refused to prosecute Secretary Treasury Steven Mnuchin’s old company OneWest for numerous foreclosures that were likely illegal.

Simply dismissing these critiques as bigotry, as Tanden and others did last week, is a lazy political strategy that smacks of tokenization, especially because much of the criticism comes from people of color on the left.

However, there’s no denying that there is a racial undercurrent to the intense scrutiny that Harris has received in recent weeks. The left is demanding that Harris, Booker, and Patrick adhere to progressive dogma to a tee. It’s a far higher standard than Bernie Sanders ever faced during his own presidential campaign. In 1990, he accepted money from the National Rifle Association. And last year he fluctuated between tone-deaf and hostile when asked about issues that affected African Americans. As recently as 2006, he was bragging that he was tough on crime due to his support for Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which has since come to be seen as a disaster for a disproportionately incarcerated black population.

It is telling that there are certain issues—mostly related to Wall Street and its corrupting influence on the party—that are considered red lines for the left, but not others, including those that directly affect African Americans. Some issues are apparently more important than others: Sanders was readily forgiven for his record’s blemishes, while Harris, Booker, and Patrick are being raked over the coals for their ties to corporate interests. That black politicians are held to different standards than white ones is particularly egregious when Harris, Booker, and Patrick are lumped together in the same breath, as though their records are identical.

Ultimately, both refusing to acknowledge that black politicians can commit political wrong and summarily dismissing them as insufficiently progressive speaks to a broader problem within the Democratic Party. Rather than seeing black politicians—and by extension black people—as human, they are instead deployed as marketing tools to bolster a narrative, whether it is one of racial progress or one of righteous class war. As Democrats head into 2018 and beyond, they have to change the way they engage with African American politicians and voters—to treat them as more than just black faces.