The signs and wonders of Colebrook, New Hampshire, begin a few miles outside town. BRAKE FOR MOOSE IT MAY SAVE YOUR LIFE; TRUMP/PENCE 2016—these placards dot the highway and continue into town, where they become gradually more depressing. GOING OUT OF BUSINESS FINAL SALE one storefront admits; it will soon join several empty neighbors. Colebrook occupies Coös County, the poorest, least populated, and least healthy county in New Hampshire. It suffers from rampant opioid abuse and a high suicide rate, not to mention the less visible hardships, both psychological and economic, that followed the loss of several major factories in the region. Residents overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump in 2016, four years after voting for Barack Obama.

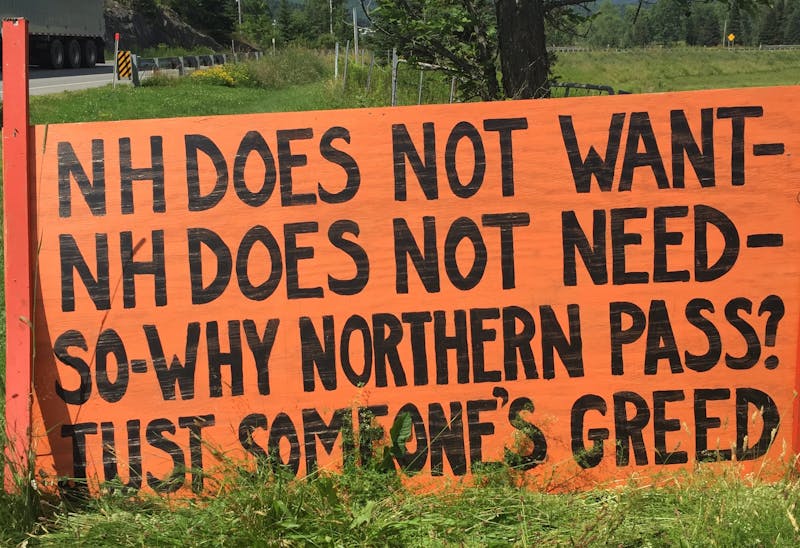

Coös County desperately needs jobs. Eversource Energy, the utility company that provides electric power to wide swaths of New England, says it has a solution: The Northern Pass project, a proposed hydroelectric 192-mile-long power line that would begin in Des Cantons in Quebec and snake through New Hampshire. According to Eversource and other backers, the $1.2 billion project will create 2,600 jobs in addition to bringing clean energy to New England. The people of Colebrook and surrounding townships, however, aren’t all persuaded. In yard after yard, alongside the ubiquitous tributes to Trump, orange signs announce NO TO NORTHERN PASS.

For seven years, a network of residents has vociferously opposed the project. They’ve staged protests, while the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests filed a failed lawsuit to halt part of the line. Now their time is nearly up. Eversource has pieced together a final route for the line despite local holdouts. It now awaits word from the federal government—the Department of Energy is set to approve or reject the permit in August, according to Eversource—and New Hampshire’s Site Evaluation Committee (SEC), which is scheduled to weigh in in September. To sway the SEC, Coös residents have constructed an unlikely alliance that crosses political, racial, and socioeconomic lines, joining hands with lefty activists from Yale and members of the Pessamit Innu First Nations in Quebec.

It is the kind of coalition that seems unique to the Trump era, when all the lines have been scrambled, pitting a restless 99 percent against the corporate interests that have infiltrated both political parties and the country’s most venerated institutions. And while it may lose this battle, its very formation points to a different sort of political solidarity, one that is emerging from the ruins of Washington, D.C.-style bipartisanship.

The unlikely diversity of this alliance stems from the opaque tangle of entities involved in Northern Pass. Yale University owns a limited liability company, Bayroot, that has partnered with Wagner Land Management to manage a 125,000-acre working forest in Coös County. Wagner is in a lease with Eversource, which is working with the Canadian utility Hydro-Québec to midwife Northern Pass into the world. The Pessamit oppose the power line because they say it will endanger their ancestral home, while the Yale activists believe that their university could pull the plug on the project by denying Eversource access to the swath of land under Wagner’s management. There’s a lot of money at stake, and the power line has enthusiastic support from Governor Chris Sununu (R), a position opponents attribute to the $18,000 he has received from Eversource executives.

The final factor is the land itself. The county sits mere minutes from the Canadian and Vermont borders. It is almost unfairly beautiful, all rolling knobs and dense forest, wreathed by fog in the morning and crowned by unblemished sky at night. It is black bear and moose country, a haven for fly-fishermen and ATV and snowmobiling enthusiasts, and many of its residents belong to families who have lived there for well over a century. For them, the thing that matters—the only thing that matters—is preserving the land. “A scar is a scar is a scar,” John Harrigan, who once owned The Colebrook News-Sentinel, tells me at his home in Colebrook. “We don’t need it.”

On this night in July, he’s joined by Rick Samson, a Republican Coös County commissioner, and Robin Canavan, a Yale doctoral student in paleoclimatology and an organizer with Local 33. Samson admits Coös is “a depressed area,” but says, “We live here because we love it.” Harrigan, whose devotion to New Hampshire’s woods has earned him the moniker the King of the North Country, adds, “There’s a great passion for the land. And Northern Pass has cut to the core of the issue.”

Samson and Harrigan don’t believe Eversource’s project will create lasting jobs or significant energy savings for New Hampshire consumers. Construction jobs are temporary by nature, and a recent analysis of the project estimates that it will save New Hampshire residents an average of only $18 a year on electricity costs. Samson and Harrigan agree that it would be preferable for the company to bury the entire power line—an option Eversource says is cost-prohibitive. (It does, however, plan to bury at least part of the line if the SEC and the Department of Energy approve the project.)

The Yale contingent represents the newest addition to the fight against Northern Pass. Yale students have made five trips to New Hampshire since discovering the university’s tangential involvement. Harrigan and Samson both believe the university could get out of its contract if it wanted to, and so do a number of Yale students and alumni who have joined the cause. Yale insists that its hands are tied, and that it has long allowed endowment partners like Wagner managerial discretion.

“The only good thing about Northern Pass so far are all the people we’ve met,” Samson says. “They’re amazing. Who would have thought we’d all work together? We’re farmers, loggers, millworkers, lawyers, doctors, and now the Yale students.” He says they even found an accidental point of solidarity: the color orange, which is worn both by opponents to Northern Pass and by members of Yale’s Local 33. “I wore my orange tie,” he says, during a trip to Yale, only to discover Yale’s union organizers in the same shade.

Liz Wyman, a 2004 graduate of the Yale University School of Forestry who is from New Hampshire, has accompanied Samson on trips to Yale’s campus in New Haven, Connecticut, to rally students against the project. Those visits haven’t always gone smoothly—Samson says that when he tried to drop off a letter for the head of the school of forestry, Yale campus police threatened to arrest him if he returned to the school. Yale spokesman Tom Conroy refused to comment on Samson’s allegations, and repeated the school’s position that it did not have the ability to intervene in Northern Pass.

Wyman doesn’t buy it. “Yale has taken the position that the lease is a done deal and that there is nothing we can change,” Wyman says. “We feel that there is definitely wiggle room for them to do the right thing and cancel their lease with Northern Pass and try to stop the project.” Canavan says, “Yale is a first-class institution, it has people who should be interested in what’s happening to the Pessamit and in New Hampshire.”

“The thing that’s really striking is that Yale posits itself as a positive force in the world,” Hannah Schmitt, a senior anthropology major at Yale, tells me. “What Yale is doing by leasing this land really goes against those values; they’re ignoring this really fierce opposition.”

Rodney McAllaster, a spare figure in worn clothes and a baseball hat, is in his barn when we pull up in Harrigan’s truck. He is milking dairy cows, which provide most of his family’s income. The McAllasters have farmed the same land for decades, and they’ve lived in the area for more than 100 years. “Just struggling,” McAllaster says. He tells me that Eversource representatives offered him $4 million for his land via an intermediary—what he calls an “unofficial” offer. He rejected it.

McAllaster owns the only operational dairy farm directly in the path of the proposed power line, and he says the project represents an existential threat to his livelihood. His farm occupies a steep hillside off Bear Rock Road in Stewartstown. Like many roads in Coös County, Bear Rock is narrow, a descendant of the ox cart trails used by early settlers. McAllaster says it’s the only maintained road available for Eversource to use, and that the presence of construction machinery will “put us out of business.” He adds, “This thing is a killer.”

“No one’s against hydro power out of Canada,” he says. “It’s just how you get it down here.” Like Harrigan and Samson, he doesn’t believe the project will actually create many jobs. “This is all about money,” he says, “it’s not about what’s best.” He alleges that Eversource representatives are so eager to piece a route together that it has encouraged families who have accepted offers to “profile” families who haven’t—making them informants of a sort. (Eversource spokesman Martin Murray dismissed this article as a “four-year-old” story in a conversation with the New Republic, and reiterated that Eversource has secured all the land it needs for its line.)

Arlene Placey, McAllaster’s neighbor on Bear Rock Road, says Eversource representatives offered her $1.4 million for her 82.6 acres of land. She also refused the offer. “This has been in my family for years, I’m not interested,” she asserts. “They said, ‘Name your price.’ I said, ‘I don’t have a price.’ The land belongs to God and I can’t take your money with me.” According to Placey, Eversource tried to sweeten the pot by offering her life tenancy on twelve remaining acres of land. This did not sway her: She says that much of her property is swampland, and that corporate representatives would not tell her which 12 acres she would be allowed to keep.

In Pittsburg—once home to the autonomous Republic of Indian Stream—John Amey takes a respite from haying to explain his opposition to Northern Pass. “It’ll be three miles from here,” he tells me in the kitchen of his farmhouse. “I’ve been against it from day one, for the whole state not just me.” Amey, who describes himself as “fairly conservative,” says he is particularly moved by the plight of the Pessamit, who believe the construction of Northern Pass would result in the construction of more dams in their already-fragile watershed. “If the whole thing was buried all the way to Deerfield, I’d stop fighting, but I’d still feel like I’ve thrown the aboriginal people under the bus,” he says. “As an old New England dairy farmer, I’ve got a lot of feelings for the Pessamit, who just want to take care of the land the way they have for centuries.”

On July 20, at the end of a suburban street in Concord, activists pack an SEC hearing on Northern Pass. The SEC has allotted three hours for testimony on the project. The audience is heavily orange, and by the time the hearing finally ends only two speakers—a small business owner and a representative of the defense contractor BAE Systems—have expressed support for the project. (BAE has offices in New Hampshire, and believes the power line will reduce energy costs.) The ratio doesn’t appear to be an anomaly: It corresponds to polling that says most New Hampshire residents now oppose the project.

“The project scares me personally,” says state Rep. Steven Rand (D-Grafton) in a prepared statement. He tells the SEC that his business, Rand Hardware, sits directly in the path of a proposed portion of Northern Pass’s buried line. “For me and my neighbor businesses, it’s a survival issue.” That sentiment is shared by the Pessamit Innu First Nations: A Pessamit delegation has traveled from Quebec to speak at the hearing, the culmination of a listening tour it conducted in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

At the hearing, the Pessamit tell the SEC that while they have no position “on the impacts of the Northern Pass project in New Hampshire,” they seek “to make New Englanders aware that 29 percent of the electricity that Hydro-Québec intends to sell was acquired in an immoral and illegal manner, to the detriment of the Pessamit.”

The Pessamit have a turbulent history with Hydro-Québec, which one Pessamit representative, via a translator, sarcastically describes to me as “a history of love.” “From the very beginning nobody from Hydro-Québec ever consulted us on anything regarding these projects. We heard nothing about it until work actually started on the project and we saw different things happening on the territory,” says another representative, Jean-Noel Vachon. The result, according to the Pessamit, is the flooding of their traditional territory and the decimation of the salmon population they’ve fished for centuries.

Another representative, Gerald Hervieux, says, “Bit by bit people are beginning to realize what the impact is on us.” Later, during a presentation at Concord’s Nature Conservancy, members of the tribe assert that Hydro-Québec’s previous constructions flooded traditional hunting grounds and dispersed fur-bearing animals, in violation of historic treaties.

Hydro-Québec disputes the Pessamit’s assertions. A spokeswoman, Lynn St. Laurent, tells the New Republic that the interconnected nature of its power grid—in which it evenly draws from multiple sources—means that the Pessamit will not bear the brunt of Northern Pass. In an email, St. Laurent adds that Hydro-Québec has “diligently consulted” with indigenous people, that it has worked to preserve the region’s river salmon population, and that the company is working with the Pessamit on another project, the Micoua-Saguenay high voltage transmission line.

But Louis Archambault, a biologist and spokesman for the Pessamit, tells me that fluctuations in energy demand mean that the salmon population may not be spared. “Even though the HydroQuebec network is integrated, when they will need peak load electricity part of it will definitely come from the Betsiamites power station,” he says, which is located smack in the middle of Pessamit territory.

With Yale sticking to its guns, the fate of Northern Pass now rests with the SEC and the very presidential administration Coös County helped vote into office. But Trump voters’ concerns about marred landscapes can’t be dismissed as small-minded NIMBYism. There are deeper currents at work here, uniting a variety of groups that, in their own ways, feel marginalized and ignored in the face of forces beyond their control.

Northern Pass’s supporters effectively say that the dispossession locals fear is no reason to halt the project. Their argument is that the collective need for clean, renewable energy outweighs the sentiments of individuals, and that the ecological impact will not be as severe as many fear. “We absolutely respect the feelings and the concerns of the people of Coös County and elsewhere here in New Hampshire that oppose the project,” says Murray, the Eversource spokesman. “But we also honestly believe that the project can be done and will be done in a way that does not detract from tourism or from the natural beauty of the state.”

This is not a necessarily conservative or liberal argument; in fact, it cuts in both directions. But though development means progress to many—to corporations selling projects, to politicians who want to create jobs—to farmers and smallholders and indigenous people it often means destruction, not just of the land itself, but of the way they live. As such, it is a question of identity.

This dilemma is not unique to Coös County. It exists in southwest Virginia, where landowners in a rural, conservative area have filed suit to halt construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline; and in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where locals are working with an order of nuns to try to stop the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline. “It’s not a political issue of the ‘left’ or ‘right’ but rather a pure issue of constitutional law and individual property rights,” an attorney for opponents of the Mountain Valley Pipeline told The Roanoke Times.

But in a more profound sense, the issue is about whether our institutions—be they located in government, education, or the corporate world—are capable of responding humanely to criticism and legitimate grievances. There is a gap between landowners and corporations, between voters and the statehouse, between students and university endowments. It is the kind of gap that sows distrust between urban and rural voters, many of whom wrap their resentment of big-city dwellers in a broader animosity toward an aloof and unresponsive government. It is a democracy gap, one that leads to the likes of Donald Trump.

The question is where people will go, and how they will express their frustration, once Trump inevitably disappoints them. Most Coös County residents wouldn’t call themselves progressive, but they are comfortable speaking in a language that resembles solidarity. They are wise to the dangers of an extraction economy, and understand in their bones the value of protecting the environment. They distrust corporations almost as much as they distrust state government and the loathed politicians in Washington, D.C. They are by no means natural constituents for the Republican Party.

But for now, they have more immediate concerns. The SEC must rule on Northern Pass by the end of September, and there is only one more public hearing left to attend.