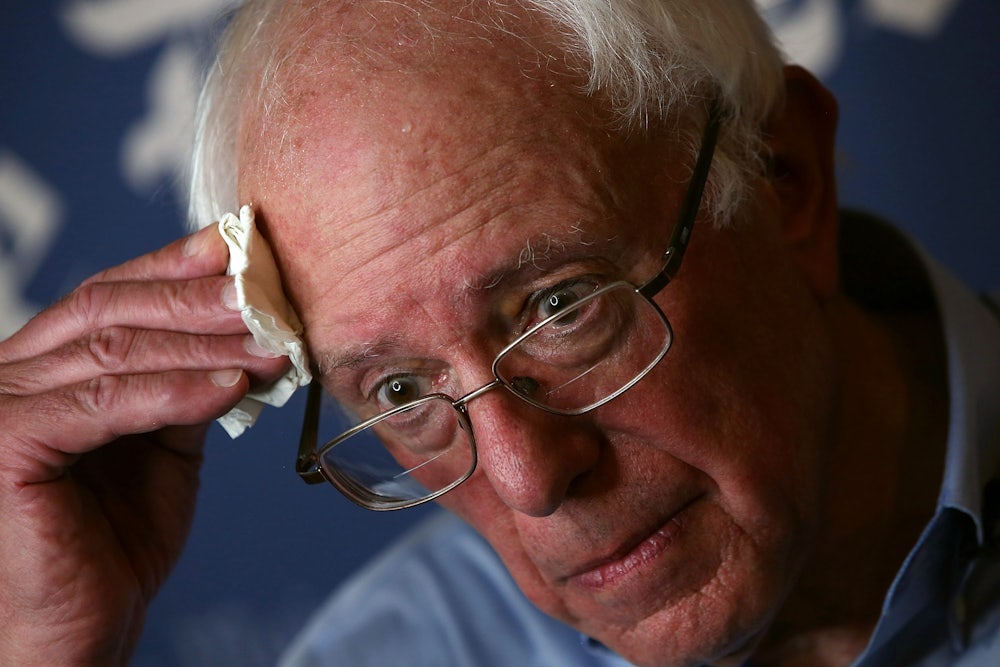

In the heat of the 2016 Democratic primary, Bernie Sanders released one of his signature proposals: Medicare-for-All. In response, economists, policy experts, and the liberal media all hammered the plan: Vox’s Ezra Klein called it “puppies-and-rainbows” and Paul Krugman wrote at The New York Times that “Sanders ended up delivering mostly smoke and mirrors.” The Urban Institute released an analysis that contended that Sanders’s proposal would have cost twice what the campaign had projected. Sanders’s plan was dragged for being vague, unrealistic, and light on the nuts and bolts.

Now, Sanders is gearing up for another go. Following the latest death of the zombie-like Trumpcare, he has stated that he will introduce single-payer legislation to the Senate. A lot is riding on the hope that Sanders’s new bill will be a robust piece of legislation. The political landscape has changed drastically since 2016, with progressives demanding more radical action to shore up and build upon the gains made by Obamacare. Among Democrats, support for single-payer has increased by 19 percentage points over the past three years. And for the first time in history, a majority of Democrats in the House have signed on as co-sponsors to Representative John Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill.

But it’s hard to deny that single-payer is an area where progressive politics has outstripped policy. Conyers’s bill is largely seen as a symbolic piece of legislation, and not only because Democrats would first have to win back Congress and the White House to even begin passing it. As Joshua Holland wrote on Wednesday in The Nation, the momentum for single-payer is “tempered by the fact that the activist left, which has a ton of energy at the moment, has for the most part failed to grapple with the difficulties of transitioning to a single-payer system.”

We have seen this dynamic play out in real time in California, where the country’s most promising single-payer bill floundered on the details of the legislation. And on a national level, there is little clarity around an actual plan with comprehensive steps to genuine universal coverage. For a party that prides itself on being the country’s only rational, empirical party, where are the Democrats’ famed wonks on single-payer?

As Harold Pollack, a health policy researcher at the University of Chicago, told Holland, “There has not yet been a detailed, single-payer bill that’s laid out the transitional issues about how to get from here to there. We’ve never actually seen that. Even if you believe everything people say about the cost savings that would result, there are still so many detailed questions about how we should finance this, how we can deal with the shock to the system, and so on.”

This failure to sketch out a plan speaks less to the pie-eyed idealism of activists than to the lack of an existing policy infrastructure in support of single-payer. This lack is most evident in the think tank class. Large policy shops like the Brookings Institution and the Center for American Progress have focused instead on criticizing Republican health care efforts or pushing for bipartisan reform options.

Smaller and more explicitly progressive think tanks, such as the Economic Policy Institute, Demos, and the Roosevelt Institute, are stacked with left-leaning scholars on subjects like the minimum wage, voting rights, and anti-trust policy, but are less in the business of churning out policy proposals for legislators, especially when it comes to health care. While some groups, such as the Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), an organization that pushes for single-payer, have been at the forefront of the issue, the bulk of the think tank world has been focused on defending the ACA.

As Adam Gaffney, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and board member of PNHP, told the New Republic, “When something seems very far away, the need for that kind of detailed policy work sometimes seems less.” But now that single-payer is no longer an idea on the fringe, the actual mechanics have to be in place to maintain its credibility. “Bernie is going to come out with a bill and I want it to be as strong as possible,” Vijay Das, senior campaign strategist at Demos, told me. “I want it to live up to scrutiny of the right and the left.”

This weakness in left-leaning policy work goes beyond single-payer. “Broadly speaking, I think left politics needs more detailed, thorough, and rigorous policy work,” Gaffney says. “We absolutely need better and more policy on the left.” While the Heritage Foundation and the Center for American Progress are seen as policy feeders for right-wing and center-left politicians, respectively, there is no such equivalent for the more progressive space. Jacob Hacker, a political scientist at Yale, points out that there are many academics doing this work outside of the think tank sphere, but as scholars they are often removed from late-in-the-pipeline policy development that is essential for politicians and policy-makers. “There is a problem in terms of progressive policy development, but it’s not a problem of there being an absence,” Hacker says. “The problem is where it’s coming from and what its character is.”

Part of the problem may stem from the Democratic Party’s technocratic bent. No one would accuse Democrats of lacking in the ability to churn out detailed and complex policy work: In the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton released dozens of policy blueprints, which continue to stand in sharp contrast to the Republicans’ brazen ignorance of the most elementary policy details. But this kind of in-the-weeds work is often removed from the long-term vision that comes with grassroots mobilizing. Liberal think tanks often work in the realm of political possibility, rather than setting ideological goals and then working towards them. This means that, with the sudden burst of energy on the left for more far-reaching policies, Democratic politics has left much of the think tank world scrambling to keep up.

Contrast this with right-wing think tanks, many of which are couched within a larger Koch network that has spent the last few decades waging a war of ideas. As detailed in Jane Mayer’s Dark Money, the Koch brothers have tirelessly poured hundreds of millions of dollars not only into electing candidates, but also into the policy arena of think tanks and universities. This investment is part of a long-term strategy to push libertarian policies, once residing on the far-right fringe, into the mainstream. While liberal policy is lagging behind liberal politics, the Kochs engineered the opposite situation, in which policy pushed politics toward their corporate-libertarian vision of society.

Much of this difference in strategy is due to the fact that the wealthy donor class is more naturally inclined to lean right. A Demos study found that Republican donors are much more conservative than Republican voters, whereas Democratic donors are more closely aligned to Democratic voters.

The right wing, led by a fantastically wealthy coterie of industrialists, has essentially weaponized policy. “Historically conservatives, particularly the Koch network, have been better at thinking of policy as a way to not only achieve technical ends but to also change the political landscape, either by weakening their opponents or strengthening their allies,” Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, political scientist at Columbia University, told me. Hertel-Fernandez sees an opportunity for the left to learn from the right by conceiving of policy as a way to shift politics in a durable way. He points to the payroll tax cuts in Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus plan, which achieved a technical end of providing workers with more disposable income, but failed to convince Americans that the equivalent of handing out cash to people is a great way to fight recessions. A majority of voters did not even know that their taxes had actually gone down. “People fixate on what are the technical fixes, but policies have to be popular,” Hertel-Fernandez says.

This shift might require bringing the grassroots into the policy shops. Experts in both the spheres of organizing and policy work emphasized that the solution does not necessarily lie in the creation of a new “left” think tank, which would only add to a crowded and fragmented ecosystem. Instead, many believe that the answer is greater integration between existing movements and policy organizations. “There’s often a disconnect between think tanks and real organizing that’s happening on the ground,” Ben Palmquist, campaign manager at the National Economic & Social Rights Initiative, told the New Republic. “We need more cross-fertilization, not just conversations and sharing of information, but actual collaboration.”

The Democratic policy infrastructure has proven itself extremely capable at churning out white papers for the center-left. Left-leaning activists and donors should be pushing this infrastructure to make an investment in more transformative progressive ends. It took years to lay the groundwork for Obamacare, and it will take years to do the same for single-payer or a similar program. Now is the time for the left to finally start waging its own war of ideas.