The feeling of being moved by architecture is a big one. Think of your very favorite man-made place to be. Does it make you feel cradled, cared for, amazed? Whatever the feeling is, it tends to rush around you like a river.

Columbus channels that sensation. It is the debut feature from Kogonada, who just goes by the one name. It follows the budding connection between Casey (Haley Lu Richardson), a smart girl in Columbus, Indiana, who is obliged to stay there to care for her mother, and Jin (John Cho), who has been summoned to Columbus from Seoul by his father’s serious illness. Their relationship builds by increments against the backdrop of their town, which happens to contain the highest concentration of Modernist architectural masterpieces in America.

We first see Casey in front of Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church, built in 1942. She is smoking a cigarette and rehearsing a tour guide’s speech. Quietly, to herself, she points out how the clock is off-center in the church’s tower; the cross embedded in its façade is also off to one side. The building is not symmetrical, but she calls it “balanced.” Kogonada’s shots follow this principle throughout the movie. Scenes are almost obnoxiously symmetrical, often structured by a face-on shot of a building, or prettily off-center and enlivened by diagonals and organic forms (a wayward path, a flower).

Jin and Casey meet one another from opposite sides of a fence. She is smoking and he is speaking Korean on the phone. He asks for a cigarette, and they have an awkward conversation. She thinks his name is Jim at first. He barely looks at her, she stares at him. From this meeting their friendship—which feels urgent and lifesaving, for they are both in limbo—plays out in gorgeously spatial terms.

Theirs is a tale of two interiors. Jin stays at an expensive-looking bed and breakfast in Columbus, but not a Modernist one: It is filled with floral upholstery and other grandmotherish touches. Casey lives in a house with her vulnerable mom (Michelle Forbes). There are two separate scenes of Casey and her mother slicing the skins off vegetables over the kitchen sink, standing side by side, belying the fact that, in a reversal, the daughter is caring for the mother.

Then there are the public spaces. Casey works at a library, where her colleague (Rory Culkin) flirts with her and tells her about his ideas. Jin is, of course, often at the hospital. In between, they ride in cars together. They visit Casey’s list of top buildings in Columbus. They stare at these buildings, stand outside them, talk about them.

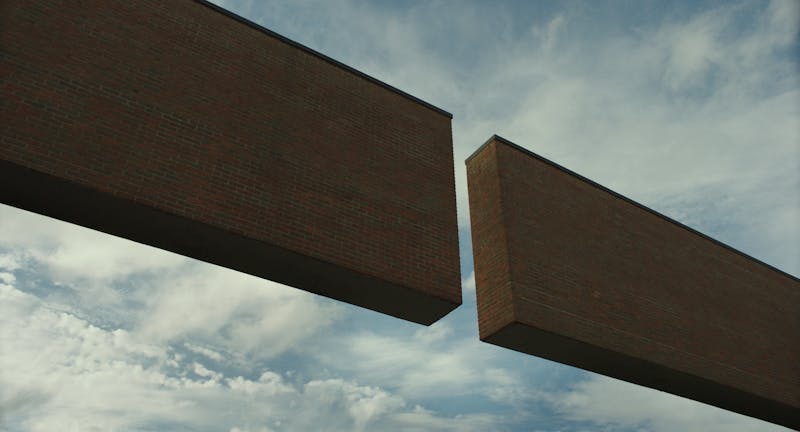

In their first moment of true intimacy, Jin asks Casey to give up her tour guide’s spiel and tell her what moves her, really moves her, about the building they are standing before. Music plays, and she is muted. Her hands wave along geometric paths and her face lights up. Columbus City Hall is a building by Edward Charles Bassett that is held by two enormous cantilevered brick “arms.” It’s like a brick wall suspended in the air, but with a slice through it. Alternatively, it looks like two loving walls, reaching for one another but not quite touching.

As a movie about intimacy Columbus is a masterpiece. In addition to his mannered architectural shots, Kogonada likes to shoot into mirrors. Casey’s eyes in a car’s rear-view mirror; Jin and his father’s friend (Parker Posey) on a couch reflected in his hotel room’s vanity mirror. Reflective surfaces are a good theme for this film, in which two very lonely people slowly begin to see themselves made better through each other’s eyes.

The press notes for Columbus describe Casey as living in “a little-known Midwestern town haunted by the promise of modernism.” That final phrase seems a perfect fit: a promise of efficiency and happiness, but one that has gone unfulfilled.

Great movies about architecture are fewer than great movies about art or music or literature. Peter Greenaway’s 1987 The Belly of An Architect has its protagonist, the extraordinarily-named Stourley Kracklite, deteriorate in tandem with the architect he is obsessed with commemorating. Various dystopian classics, from Metropolis to Blade Runner, fill their worlds with futuristic buildings. And Godfrey Reggio’s glorious experimental work Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance (1982) is made of slow, bizarre shots of natural forms and city scenes across America. Hitchcock made great play with houses, of course, with the metaphorical mansion of Psycho (1960), the perspective tricks of Rear Window (1954), and the bonkers Vandamm House of North by Northwest (1959).

Columbus isn’t quite like these movies. Instead, it has more in common with works about subtle human emotion that just happen to pay extremely close attention to their built environments: films like Luca Guadagnino’s 2002 I Am Love, which gazed upon Milan’s Villa Necchi Campiglio; Antonioni’s industrial love letter Red Desert (1965); or Brian de Palma’s Body Double (1984).

In the climactic moments of Columbus, Kogonada takes things away. He removes the sound of conversation, or he takes the buildings out and focuses instead on trees and flowers. His actors’ performances are very strong, and fans of Cho will be thrilled to see him finally take on a more muted, sophisticated leading role. But in his aesthetics of subtraction, which does not reduce but instead amplifies the emotional stakes, Kogonada layers a formal modernism over his actors’ performances. In this way, the architecture of Columbus, Indiana, and the architecture of this film achieve a harmony rare in contemporary cinema. Like the modernist greats, Kogonada promises much.