In 1969, ahead of his 70th birthday, Vladimir Nabokov was asked a rather audacious question by a reporter from The New York Times: “How do you rank yourself among writers (living) and of the immediate past?” Nabokov reportedly replied by describing a form of communication that had yet to be invented: “I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket, which I would now like to trace in reply to your question.”

It wasn’t until 1999, many years after his death, that Nabokov’s wish was granted. That was the year that Shigetaka Kurita developed the first set of emojis, 176 in total, for the Japanese telecom company NTT Docomo. (E moji translates to “picture character” in Japanese.) These early emojis, designed for cell phone screens, were 12 x 12 pixels large. The icons included a sun, a train, and a game controller. Looking at them now evokes the quiet charm of early internet pixel art; just a few dozen points strung together, and a high-heeled shoe or a rocking horse appears.

The emojis that we are familiar with today were made popular by their inclusion in Apple’s first iPhone in 2007. These emojis were hidden in a keyboard meant solely for Japanese users, but people around the world promptly dug them out. Emojis faced backlash from the beginning, often being associated with frivolity and stupidity. “I am deeply offended by them,” Maria McErlane, a British journalist and actress, told The New York Times in 2011. “I find it lazy. Are your words not enough? To use a little picture with sunglasses on it to let you know how you’re feeling is beyond ridiculous.”

Another critic lamented to the Times that emojis signaled the end of language: “They’re part of the degradation of writing skills—grammar, syntax, sentence structure, even penmanship—that come with digital technology.” People have warned against using them in the workplace due to their unprofessionality. The use of the emoji has, above all, been chastised for being childish.

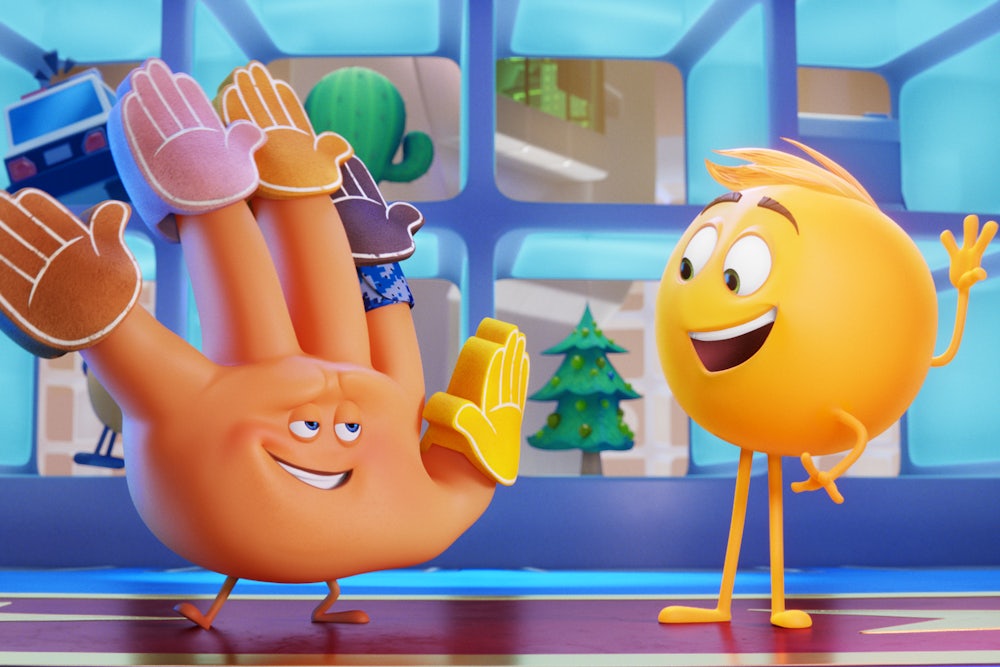

In 2017, such criticisms have been relegated to the luddite realm. In the age of social media, texting, and digital work platforms like Slack, emojis have become universal. Their very ubiquity has made them ripe for crass commercialization, which is why we now have The Emoji Movie. The movie has been widely (and rightly) panned—it has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 8 percent—but its most egregious flaw is that it packages itself as a children’s movie.

The Emoji Movie is set inside a smartphone. The story follows Gene, a “meh” emoji who leaves the text messaging app to join up with Jailbreak, a princess emoji who is really a hacker in disguise. They adventure in and out of various apps to escape the phone and reach the cloud (their motivations for doing so are really not worth mentioning). Some critics have compared it to a low-rent Inside Out, but the movie is really like a very uninspired and hackneyed version of Wreck It Ralph.

It would be hard to forgive The Emoji Movie its “meh” plotline and the fact that it is literally one giant ad for apps, but its most unforgivable sin is that it perpetuates the notion that emojis are childish. There’s a reason Hillary Clinton took so much flak in 2016 when her campaign tweeted to her followers, “How does your student loan debt make you feel? Tell us in 3 emojis or less.” This was mocked because it was a shallow and transparent attempt to pander to young voters, which in turn made it clear that the Clinton campaign condescendingly viewed the form as one used by immature simpletons.

Why the patronizing attitude? It is partly because emojis are relatively new, but also because they are unapologetically fun. However, their sunniness does not connote an innocent simplicity; in fact, they serve a real psychological purpose, which is to soften the harsh edges of internet life.

While it’s true that emojis were originally created by Kurita for teens, those teens were the first to have come of age with little memory of a non-internet world. And everyone in this generation knows that the online world is a terrible, terrible place. The 2016 election brought this reality into sharp relief; anyone who expressed a political opinion on the internet was likely to have felt the wrath of misogynist and racist trolls and harassers. The Emoji Movie even includes a plotline about internet trolls who spend their time heckling the movie’s heroes, the emojis.

The emoji is often used as an antidote to the trolls. Because they are small cartoons, they are always—perhaps sometimes insufferably—happy. As Adam Sternbergh wrote in New York magazine, “It’s frankly pretty strange that, in an online climate that is constantly being called out for excessive aggression and maliciousness, emoji have no in-built linguistic capacity for meanness. There are angry faces and frowning faces and thumbs down and even the so-called Face With No Good Gesture, which, in the Apple set, is a woman with her arms crossed in an X. But, seriously, look at her: 🙅. The Face With No Good Gesture has never actually hurt someone’s feelings.”

According to emojitracker.com, which records real-time emoji use on Twitter, the most used emojis are all happy ones—the joyful crying face, the heart, the face with heart-eyes. This ceaseless positivity may be annoying to those of an older generation, but it’s one of the few ways to balance the cynicism and derision and hate that proliferate on the internet. Perhaps the best example of someone using emojis to combat online harassment is Chelsea Manning, who faces some of the most extreme abuse on Twitter:

who ? the american people are now your enemies ?? 😎🌈💕 #WeGotThis https://t.co/pJcW2pRmIk

— Chelsea E. Manning (@xychelsea) July 26, 2017

never 😁💕 https://t.co/keIZ2DhyOi

— Chelsea E. Manning (@xychelsea) July 26, 2017

probably not very healthy 😬 id rather take a spironolactone 😇🌈💕 https://t.co/ODNCsSRFVB

— Chelsea E. Manning (@xychelsea) July 20, 2017

Manning’s emoji-laden responses are far from frivolous or childish or simple. The emojis allow Manning to respond to the trolls, but without succumbing to their trolling. As Eve Peyser writes at Vice, “Among the utter darkness of the Trump-era internet, Chelsea Manning is a beam of light.”

Even in the 1960s, Nabokov reportedly described a proto-emoji to soften his response and give it ambiguous nuance. He chose a coy smile, rather than a straightforward refusal to answer the question. The Emoji Movie might be a trite and uninspired, but emojis themselves are not. They are the shining chef kisses of joy (👨🏻🍳 😘 👌) in the hellscape of online. As Kurita once said, the idea for emojis all “started with the heart icon. That’s how it all began.”