Paul Begala, the Democratic consultant and longtime adviser to Bill and Hillary Clinton, is a reliable bellwether for the party’s centrist wing. As such, Begala rarely surprises, but last week he made a startling remark about how the U.S. should respond to Russian interference in last year’s presidential election. “We were and are under attack by a hostile foreign power,” Begala said on CNN, where he’s a contributor. “We should be debating how many sanctions we should place on Russia or whether we should blow up the KGB...”

Hmmm... uhh... so here's Paul Begala, top Clinton ally, saying Trump should consider bombing Russia. https://t.co/2tW1gI0Uxh pic.twitter.com/wo9BmJPNDb

— Andrew Kirell (@AndrewKirell) July 13, 2017

Begala’s statement can’t be dismissed as the intemperate remarks of a courtier still disappointed over an electoral loss. Rather, it joins a steady stream of comments by prominent Democrats who talk as if the United States were at war with Russia—hyperbolic rhetoric that risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal, also last week on CNN, said that the Trump campaign’s meetings with Russian officials “could rise to the level of espionage and treason.” He added, “Remember, Russia is a dangerous adversary who attacked the United States. I’d argue to you that it was an act of war by an enemy...”

Blumenthal on the Don Jr. meeting: "It could rise to the level of espionage and treason." https://t.co/jqLQEKEHcu

— Kyle Griffin (@kylegriffin1) July 13, 2017

Donna Brazile, the former interim Democratic National Committee chairwoman, has also used the phrase “act of war”—in echoing remarks by former Vice President Dick Cheney, no less. “I’ve never agreed with Dick Cheney in my entire life, but when he said this was an act of war, I have to agree with the former vice president,” she said in March. “It was an act of war.” Democrats in Congress have made similar statements. “I think this attack that we’ve experienced is a form of war, a form of war on our fundamental democratic principles,” Representative Bonnie Watson Coleman of New Jersey said. “This past election, our country was attacked,” Representative Eric Swalwell of California said. “We were attacked by Russia.”

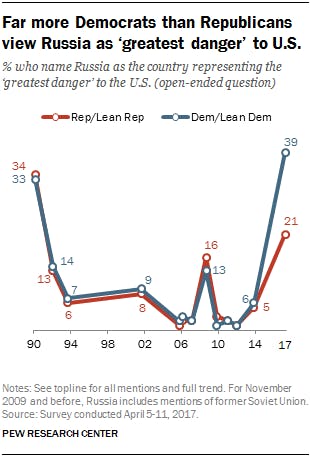

These comments reflect a broader trend among Democrats. Historically, since 1990, a roughly equal percentage of Democrats and Republicans have considered Russia to be the “greatest danger” to America. But a Pew Research poll released in April found a sharp rise since 2014 in Democrats who believe as much, the highest percentage since the end of the Cold War: 39 percent believe Russia is the “greatest threat,” versus only 21 percent of Republicans.

There are many reasons for the turn against Russia by rank-and-file Democrats and party leaders. The strong evidence of Russian interference in the election, and the Trump campaign’s collusion with Kremlin-connected operatives, allow Democrats to blame Russian President Vladimir Putin in part for a bitter electoral loss. (Conversely, most Republicans seem inclined to give Russia a pass because they don’t regret the election outcome. In point of fact, we’ll never know for sure whether Russian interference was a decisive factor or not.) Democrats also detest Russia as a global promoter of illiberal values like xenophobia and homophobia. And politically, hyping the Russian threat exploits a rift in the Republican Party, where major figures like senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham remain hawkish and uneasy with the Trump administration’s friendliness toward Putin.

Still, the belligerent rhetoric from the likes of Begala and Blumenthal is dangerous. To bluster about Russian actions being an “act of war” is to suggest that the U.S. may actually have to go to war with Russia, or risk appearing too weak to defend its own sovereignty. Yet aside from Begala’s comments about bombing the KGB, there’s little explanation from these Democrats about what a war with Russia, a nuclear power, would look like.

It’s worth contrasting the wild talk about bombing Russia with the policy of President Barack Obama: economic sanctions, the dismissal of diplomats, and potential retribution in the cyber realm. As The Washington Post reported in June, Obama in late December “approved a previously undisclosed covert measure that authorized planting cyber weapons in Russia’s infrastructure, the digital equivalent of bombs that could be detonated if the United States found itself in an escalating exchange with Moscow. The project, which Obama approved in a covert-action finding, was still in its planning stages when Obama left office. It would be up to President Trump to decide whether to use the capability.”

Cyber warfare is a murky realm, but it’s clear that Obama’s preference was for a modulated approach that would punish Russia’s norm violations by reacting in kind, but stay well short of a conventional military war. He took this approach because he correctly viewed Russia as a weak state trying to compensate with norm violations, but lacking in the resources to be a real threat to American power. In 2013, Obama dismissively referred to Putin as someone who can act “like a bored kid in the back of the classroom.” By this judgement, Russia, with its decrepit oil-based economy (roughly the same size as Italy’s economy) and general lack of soft power (because Putin’s own actions have made Russia unpopular in Europe and many other parts of the world), is more an irritant than a major problem. So Obama opted to contain Russia rather than fight it directly.

His approach, widely derided by GOP hawks, remains the right one. To abandon it, and make common cause with McCain and Graham, would be to accept their reckless threat inflation and the foolish belief that the U.S., still bogged down in the Middle East, can afford another major conflict. Trump’s coddling of Putin deserves to be criticized, and Russia ought to be punished for its election interference and prevented from doing it again. But this can be accomplished without borrowing language from Dick Cheney, of all people. Instead, Democrats should realize that their last president laid out a nuanced approach that looks more and more sensible every day.