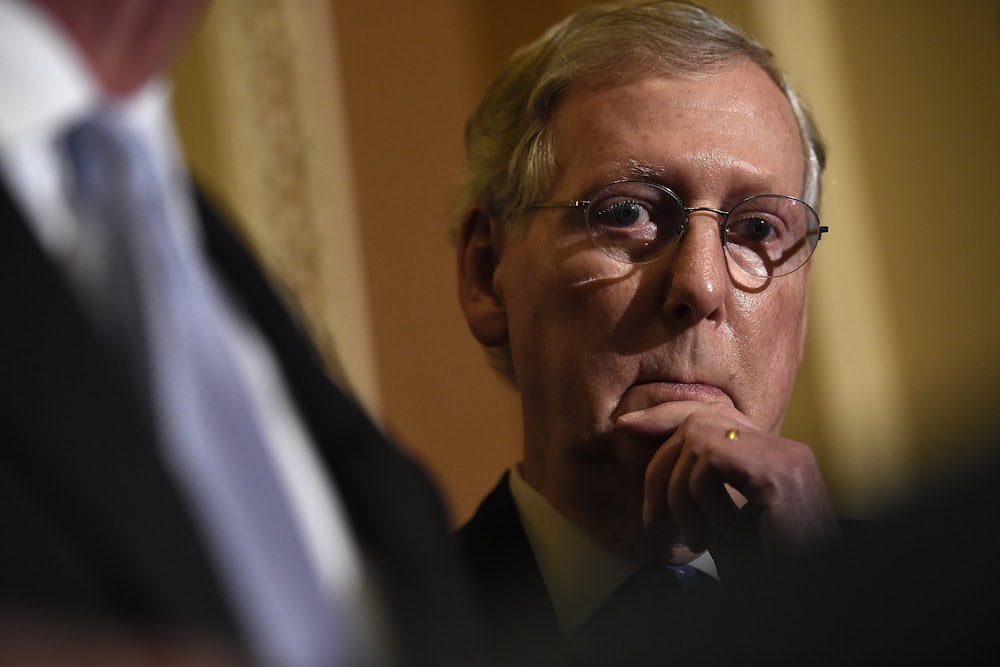

As it was becoming clear last week that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell would have to return to the secrecy of his Capitol Hill suite and tweak or rewrite his health care bill, thousands of supporters of the Affordable Care Act were marching outside, joined by Democratic senators and congressmen.

McConnell’s troubles, and the coinciding protests, fit together neatly. They told the story of a Republican Party knocked back on its heels by a popular backlash to the odious and unpopular policies they were trying to foist on the public. With the exception, perhaps, of the House GOP’s early stumble—when Speaker Paul Ryan had to pull his version of Trumpcare from the floor before a vote—this was the high-water mark for the Trump opposition. It proved that under a consistent spotlight, legislation as cruel and corruptly conceived as the Republican health care bills would have a very hard time becoming law.

And yet, the next turn in the story was eminently predictable.

“I’m nervous that the TV networks don’t think that this gets eyeballs like Russia does and some of these other issues,” Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy told the hosts of the liberal podcast Pod Save America. “And so we are going to have to create news. We are going to have to build crowds like this in every state to make sure that TV cameras have to turn out.”

Murphy was echoing his concern for what I described last week as the media’s bias toward “new” news—and the corollary tendency to give short shrift to live issues that haven’t changed much. McConnell’s secret bill writing process exploited that bias, but eventually GOP health care reform had to become news.

The unveiling of the Better Care Reconciliation Act was new news.

The dreadful CBO impact analysis was new news.

Each statement of opposition by a mortified GOP senator was new news.

And, of course, the delay of the Senate vote amid a large public protest was new news.

But once the bill stalled, Republicans were able to seize control of events once again.

As of this writing, only two GOP senators—Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Jerry Moran of Kansas—had scheduled July 4 recess town halls in their states. McConnell has pulled the bill back behind the veil, changing it in ways we won’t know until he unveils it once again—perhaps after the fix is already in. Activists can confront members on the sidelines of Independence Day parades, but they can’t force senators to answer any questions or make any public commitments.

The erosion of media interest in the Republican health care bill over the past five days has been palpable. That’s a shame because, though there’s nothing scoop-like about it, the story of the past week and a half has been extraordinary. It isn’t the media’s job to defeat the BCRA, or any piece of legislation, but the thud-like landing of McConnell’s bill is incredibly damning.

It was theoretically possible that after drafting a bill in the dark for weeks and weeks, McConnell would unveil it, and the public would love it. Democrats would feel pressured to support it. Republicans wouldn’t have to run from reporters in the hallways of the Capitol. What happened instead, once the new news poured forth and the entire media was swimming in it, is that the legislation failed to survive a full week of sustained coverage.

Activists in states are trying, as Murphy suggested, to make new news. A group of disabled protesters conducted a sit-in at Colorado Senator Cory Gardner’s office in Denver, until they were arrested Thursday night. Obamacare supporters are organizing rallies in key states. But whether these events command national attention wouldn’t be an open question if the new news bias didn’t have such disproportionate influence over editorial decisions.

MSNBC’s Chris Hayes was a lonely voice on television turning the secrecy of the health care process into a story unto itself. But the example he set proves there is a way to prioritize the public interest in knowing that the leaders of Congress are trying to expedite a horribly unpopular piece of national legislation as quietly as possible—even if there’s no new news to report.