On the Sunday before Christmas, in 2015, Hal Howard was pulling away from a party at his pastor’s house when he saw, standing in the street in front of him, a little girl. Howard slowed his pickup truck to a stop and tooted his horn. The girl didn’t move. At the same time, the girl’s father, Yousef Muslet, was playing with one of his sons on their front lawn. Muslet’s house sits opposite the pastor’s, in a prim, suburban neighborhood of Belle Glade, Florida. When Howard began honking at his daughter, Muslet walked up to the truck and introduced himself.

The conversation between Howard and Muslet was brief, no more than five minutes. At one point, near the end, the two men shook hands. Finally, Muslet gathered up his children and headed inside. As Howard drove away, his friend Pat Lucey, who was sitting in the passenger seat, wished Muslet a merry Christmas.

Nine days later, Muslet was at home, talking on the phone with his accountant, when he heard a knock at his door. He opened it to find a half-dozen deputies from the Palm Beach County sheriff’s department. A deputy asked Muslet if he recalled a discussion from the previous week, one in which he had mentioned Allah. Muslet replied that he had a lot of conversations and he talked about Allah a lot. Then Hal Howard appeared on his sidewalk. He pointed at Muslet. “That’s the guy,” he said. Another deputy stepped forward with handcuffs and informed Muslet that he was under arrest. He was placed in a police car and taken to jail.

Earlier that afternoon, Howard had walked into the sheriff’s department and told the deputy on duty that he was afraid. His talk with Muslet had left him deeply unsettled. His concern, he said, centered on the handshake. As Howard told it, Muslet had gripped his hand forcefully and yanked his arm, as if trying to pull him through the driver’s side window. Howard, who was 75, struggled to let go, but Muslet had overpowered him. According to a police report, Howard said that Muslet “had a strange look on his face during the entire encounter.” Muslet also yelled “Allah! Praise Allah!” which left Howard even more frightened. After a half-minute of grappling, Howard was finally able to pry his hand free and speed away.

Given his age and Muslet’s strength, Howard felt lucky he hadn’t suffered more than a sore shoulder. At first, worried that he was overreacting, he hesitated to report the incident. But more than a week later, at the urging of family and friends, he decided to tell the police.

Muslet was charged with two felonies: battery on an elderly person and burglary. (Under Florida law, burglary includes unlawfully entering a vehicle with the intention of committing a crime.) Muslet had lived in Belle Glade since he was twelve. Now 51, he owned a local clothing store with his brothers. His criminal record showed nothing more serious than speeding tickets. The handshake with Howard, Muslet insisted, had seemed friendly. Yet if he was found guilty of both charges, he faced a maximum sentence of life in prison.

The handshake, it is said, was a ritual conceived in mistrust, for the purpose of making peace. Its origin dates at least to classical antiquity, when Greek foot soldiers joined palms to demonstrate they carried no weapons. Gradually, shaking hands evolved into a ceremonial greeting between strangers. The gesture, though, never quite lost its hint of threat. President Trump, whose grasp is unabashedly combative, has managed to bring the act full circle, transforming a sign of unity into a new form of warfare.

When I meet Hal Howard outside his trailer in February, the first thing he does, naturally, is present his hand. “The proper handshake,” writes Emily Post, “is made briefly; but there should be a feeling of strength and warmth in the clasp.” By this definition, Howard’s is textbook. His demeanor, though, is reticent, almost stoic. He has light blue eyes, sun-mottled skin, and thin, white hair, high and tight, as he’s kept it since his Army days. On his right index finger he wears a big, gold ring marked with a Latin cross—“just to let people know where I stand.”

Howard drives me in his truck, a shiny, white Dodge Ram 1500, to a nearby Dunkin’ Donuts. He lives in Clewiston, a town over from Belle Glade. Both are in the heart of sugar country, surrounded by acres of cane fields. During the harvest season, the fields are regularly set on fire. Burning off the plant’s leaves—known, in the industry, as the “trash”—eases access to its sucrose-rich stalk, which is then cut off and trucked to a mill for processing. In the distance, as we drive, a sloppy cloud of brown smoke rises from a vast sea of green. Above the flames, a cauldron of raptors hovers, waiting to snatch up fleeing rabbits and rats. When I mention Clewiston’s motto—“America’s Sweetest Town”—Howard frowns. “That’s a lie,” he says. “They get that sugar cookin’, it smells like a pig farm.”

As we sip coffee, Howard, who is originally from Kentucky, tells me he used to own a construction business in Fort Lauderdale. Now, in his retirement, he stocks shelves at the local supermarket. He lives a simple, abstemious existence, the orbit of which encircles his church. For two decades, Howard has sworn off liquor, cigarettes, women, and other fleshly temptations. His chief indulgences are watching television and washing his truck. It was at a church in Clewiston that he met Pat Lucey—“my Christian brother.” Howard, a divorcee, and Lucey, a widower, quickly became close. The two men now share a trailer and a dog, a Chihuahua–German Shepherd mix named Mr. Whitey.

In 2015, the church in Clewiston suffered a schism, and Howard joined some of the congregation in defecting to another, in Belle Glade. He had only known his new preacher for a couple of months when he attended his party. Howard had stayed for an hour, nibbling on finger foods, then left with Lucey, filled with the Christmas spirit. He was surprised when Muslet approached his truck, but he only got nervous when Muslet began discussing religion.

“At first, I thought he just wanted to talk to somebody,” Howard tells me. “But then, as the conversation went on, I realized he was trying to get into my Christianhood.”

According to Howard, one of the first things Muslet asked him was the name of his god. He readily replied that his lord and savior was Jesus Christ. This didn’t seem to satisfy Muslet, who continued to pepper him with questions about his faith. After a minute, Howard realized that Muslet is not actually Christian—he’s Muslim. At one point, he even offered to share the tenets of his own faith with Howard’s fellow parishioners.

“He said he would like to come to our church and teach everybody how to be a Muslim,” Howard recalls, incredulous. “I said, ‘Well, you’re welcome to come to church, but we don’t want to hear anything about a Muslim. We believe in Jesus.’ ”

The longer the conversation went on, Howard says, the louder and angrier Muslet got. Howard wanted to leave, but Muslet’s daughter was still blocking his way. When Muslet finally extended his hand, Howard took it eagerly, hoping the talk was drawing to a close. The violence of the handshake—and what he saw as Muslet’s evident sadism—shocked him.

“The whole time, he’s laughing and smiling,” Howard says. “Got a big smile on his face. And that really turned a button on me.” As they struggled, Howard kept telling Muslet to let go. Howard thought about hitting him, but he was strapped in his seatbelt and his left arm was pinned to his side. “I called him a choice name or two,” he says. “It’s hard to be a Christian when you’re being mistreated.” Finally, Muslet backed away, leaving Howard’s shoulder throbbing.

Howard was mad. Still, he told himself he was making too much of it. It was only after he discussed the encounter with his sons and his co-workers at the supermarket that he changed his mind. Muslet, they warned, could be dangerous. Ultimately, Howard says, he went to the police out of fear that Muslet might hurt someone else.

I ask Howard whether Muslet’s being Muslim had anything to do with his decision to report the incident to police.

“Before you go to the wrong place,” he says, “I don’t hate Muslims. And I can prove I don’t. Because, for the last three years, my doctor was a Muslim. And I love the man.”

Not long ago, Howard contracted throat cancer—a common affliction, he says, in smoke-choked Clewiston. Friends recommended a Palestinian doctor named Abdel Kaki, who has won Howard’s trust through sound medical advice and a patient bedside manner. While Howard has no objection to “plain” Muslims—“the ones that come here to be part of America”—he believes the “radical” ones need to be watched. Dr. Kaki, for example, is a plain Muslim, an upstanding citizen and asset to the community.

“I think,” Howard says, “he might actually be a Christian Muslim.”

Based on his encounter with Muslet, though, Howard guesses that he’s probably a radical Muslim. “You can tell ’em by what they do, the way they act,” Howard says. “If they’re against Christians, that’s a pretty good sign.”

I ask Howard where he gets his information about radical Muslims. He motions with his cup to a television mounted above my head. I turn and see that it’s tuned to Fox News.

“That’s my channel,” he says.

Before we part, Howard asks me if I go to church. I say I was raised Episcopalian, but am now agnostic. He looks alarmed.

“You need to go to church,” he says. “I’ll be real truthful with you. He’s coming real soon. Read the Bible. Everything in Revelations is happening now.” The culture, Howard says, growing animated, has lost God. The signs are everywhere. A corrupt government. Gay marriage. Kids killing parents. Nearly naked women broadcast on network television. Salvation-wise, it’s now or never. Howard tells me that for many years, he lived in sin—“I did my thing, not God’s thing.” Then, in his early fifties, he had an affair with a married woman. The Lord did not approve. Howard tried to end it, but one day, the woman called him again. Howard knew, in his heart, he shouldn’t see her, but he went anyway. As soon as he got home, his blood pressure shot up to 192 over 90, and it stayed like that for a week. Then God came to Howard, in his mind. The blood pressure spike, the Lord said, had been a warning. He put matters plainly: Howard was going to do God’s thing now.

“Yeah, He’s real,” Howard says, fingering his gold ring. “And He’s going to hurt me if I don’t do what He says.”

After seeing Howard, I drive to the other, more famous side of Palm Beach County—the Mar-a-Lago side—to an event at the Royal Palm Yacht & Country Club in Boca Raton. Inside the club’s vast ballroom, a capacity crowd of mostly elderly couples sit at white linen banquet tables, snacking on canapés. At the front stands a handsome, polished man in his late forties, wearing a crisp, blue blazer with an American flag pin. Dr. M. Zuhdi Jasser is a practicing physician who lives in Phoenix, Arizona, but he enjoys a second career as a political commentator on radical Islam who appears frequently on Fox News.

Taking the podium, Jasser compares the religion of Islam to a sick patient in need of urgent care. Terrorism, he says, is just a symptom of this disease. The bigger threat is ideological. Islamists—those who practice “political Islam”—don’t believe in a separation between mosque and state. Instead, they advocate the adoption of Koranic law, or sharia. Political Islam, Jasser says, sends adherents down a “conveyor belt” of radicalization. He cites the Tsarnaev brothers, who bombed the Boston marathon, as an example of the danger in assuming Muslims are peaceful without interrogating their beliefs.

“The narrative about them is that they appeared to be normal American Muslims,” Jasser says. “How do you know they were normal? Do we know what they believed about the state, about the Constitution? No. The fact that they had a cell phone, or drove a motorcycle, or were trying to make the Olympics—that doesn’t make them normal.”

According to the most recent estimates, Muslims make up approximately 1 percent of the U.S. population. In Palm Beach County, they are more than twice that. Whether in spite of, or because of, the local demographics, Palm Beach has become one of America’s most concentrated hotbeds of anti-Islamic sentiment. Until 2013, the county was represented in Congress by Allen West, a former Army officer who denounces all of Islam as a “totalitarian theocratic political ideology.” The Southern Poverty Law Center has identified three groups in Palm Beach County that espouse anti-Muslim views—including Citizens for National Security, the organization that is hosting Jasser’s appearance at the yacht club. Founded in 2008, the group believes that thousands of Muslims are seeking to infiltrate American institutions to undermine them from within, and that the Tsarnaev brothers were radicalized by a pro-Islam bias in their history textbooks. In a recent YouTube video, the group warns of a new “breeding ground for homegrown terrorists that few are aware of—American classrooms!”

As the sociologist Christopher Bail traces in his 2015 book, Terrified, organizations like Citizens for National Security have spread rapidly since the attacks on September 11—funded, in his estimate, by at least $245 million in donations, much of it “dark money” from private, right-wing foundations. The money has been used to bankroll an army of dubiously credentialed experts, who argue that Muslims are waging a “stealth jihad” against democratic institutions. In this mind-set, requests by Muslims for basic religious accommodation—foot baths at airports, say, or designated prayer rooms at work—are understood as covert attempts to implement sharia. Left unchecked, such incursions would, they fear, eventually usurp the U.S. Constitution.

The influence of these groups has helped, in little more than a decade, to fundamentally reshape American views of Islam. In a poll conducted in 1993, nearly two-thirds of Americans had no opinion, favorable or unfavorable, of Muslims. By 2011, a majority looked at Islam unfavorably. In one poll, only a third of Americans considered Muslims in the United States to be “trustworthy.” Ten state legislatures have passed bills banning sharia, and hate crimes against Muslims have reached a level not seen since 2001. A few weeks before Muslet’s arrest, a 27-year-old man was charged with vandalizing an Islamic center in North Palm Beach. Last November, a mosque in Boynton Beach was defaced with the words FUCK ISLAM.

Jasser differs from much of Fox’s commentariat in that he is a practicing Muslim, one who has positioned himself as a Luther-like reformer, promoting a “spiritual,” apolitical interpretation of his faith. In his opinion, many Muslim-American groups are, in fact, fronts for political Islam. In Boca Raton, he repeats again and again that his criticisms are not aimed at Islam as a whole, but at a certain, unspecified percentage of its adherents. The crowd seems fully with him; when a woman with long blond hair asks Jasser why he doesn’t just convert to Christianity or Judaism, she is roundly booed. At the same time, Jasser’s logic suggests that every Muslim American must be viewed as an existential threat until demonstrated otherwise.

The morning after Jasser’s talk, Fox News carries a short article noting that an arsonist has set fire to a mosque in Tampa—the second such case in Florida in six months. On the radio, two local talk show hosts, after reviewing a new Mediterranean restaurant—“I wasn’t in love with the baklava”—chat matter-of-factly about the Obama administration’s infiltration by Muslim extremists.

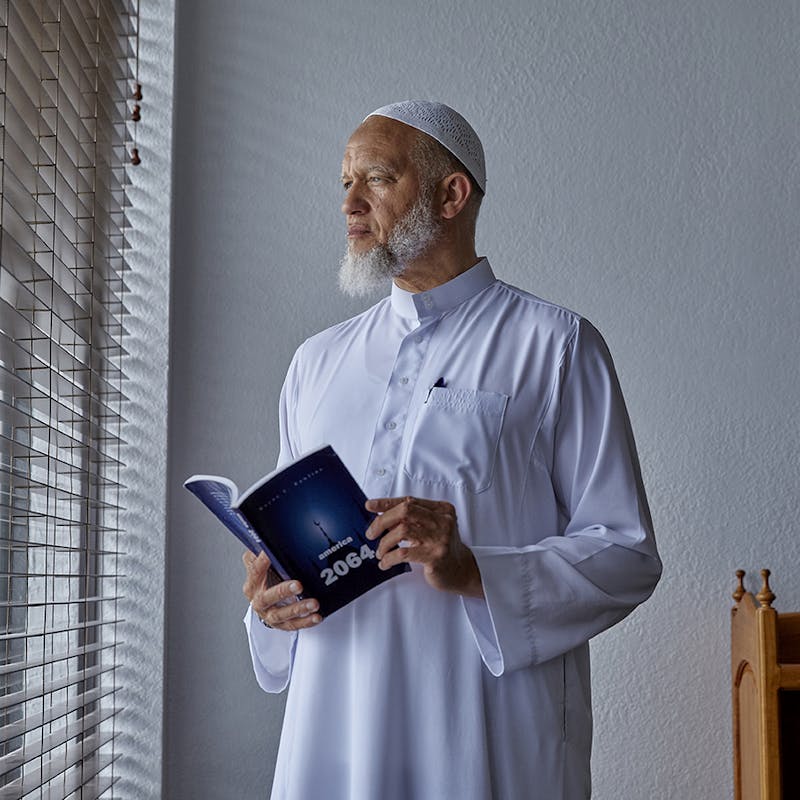

One of Yousef Muslet’s attorneys described his client to me as a “visible Muslim.” As I watch Muslet pull up in front of the Belle Glade mosque a few minutes before Friday prayer, I have a hard time believing that Hal Howard had mistaken him, even momentarily, for a brother in Christ. Muslet wears a blinding white thawb and a multicolored keffiyeh; his face is dominated by a colossal salt-and-pepper beard, dense and impeccable, like topiary. When Muslet sees me, he bounds up and, forgoing a handshake entirely, engulfs me in a bear hug.

In Muslet’s version of his encounter with Hal Howard, the handshake was an attempt to defuse a tense situation. “I offered my hand in peace, bro,” he tells me. Muslet was born in Palestine but aggressively inhaled the idiom and drawled speech of his teenage years in Florida. This seeming mismatch has a disarming effect on strangers. “People sometimes get nervous when they see me,” he says. “But when I start talking, they usually calm down.”

As Muslet remembers it, when Howard started yelling at his daughter to get out of the street, Muslet had sought to soothe him. “I’m like, ‘Just chill.’ The way he was trying to rush out of there, and my kids are playing in the street? You can’t be driving through a neighborhood like that. Bottom line? I was a concerned father.”

Muslet denies being upset when he approached the truck, though he does admit, as Howard alleged, to bringing up religion. After learning that Howard was coming from his neighbor’s Christmas party, Muslet asked him a question he likes to ask a lot of non-Muslims.

“I asked him, ‘What’s God’s name?’ And he said ‘Jesus.’ And I said, ‘OK, but isn’t Jesus the son?’ And he said, ‘Yeah.’ ‘OK,’ I said, ‘so, what’s the father’s name? What’s God’s name?’ And he says, ‘Well, uh, God.’ And I said, ‘No, no, no—God is who he is. But what’s his name? Because I’ve learned his name, and I would like to share it with you.’ ” Muslet then revealed to Howard that God’s real name is Allah. “And Hal says, ‘Well, my lord and savior is Jesus Christ.’ ”

I ask Muslet why he decided, at that precise moment, to try to educate a 75-year-old Southern Baptist—one fresh from a Christmas party at his preacher’s house, no less—about Islam. Muslet says he saw the encounter as a “teaching moment.” Everyone, he explained, worships the same God. Giving dawah—inviting people into Islam—is an important part of his faith.

At the mosque, Muslet introduces me to two of his sons—he has ten children in total, six with his current wife—and a man named Wayne Rawlins, whom he considers his best friend and spiritual mentor. Rawlins—a tall, lanky black man with a loose, goofy smile—is the author of a book about Islam that Muslet found enormously inspirational. “Wayne’s the power, man,” Muslet says. “Me? I go more on impulse. But Wayne, he has a plan for everything.”

After ablutions, we follow several dozen men into the mosque’s prayer hall. Muslet and Rawlins are the only people, besides the imam, wearing robes; the other men, wilting in the late-winter heat, favor khakis and short-sleeve shirts. As the imam delivers a brief sermon about the importance of being steadfast and straight in your faith—interrupted occasionally by the faint beep of a smoke detector—Muslet and Rawlins sit just in front of the lectern, staring up, eyes alight, like keen students, as Muslet’s children slouch against them.

When the imam finishes, Muslet stands and faces the congregation. Seeking to become more involved in civic affairs, he is running for city commissioner.

“Guys,” Muslet says, “some folks are going around whispering that there’s a Muslim running for commissioner. Well, it’s true and, man, it’s a good thing. Belle Glade needs Muslim leadership. Some of you might not want to be part of a corrupt system, but it’s a Muslim’s job to lead. So make sure to get to the polls, vote, and get me in that seat!” Like a true politician, he then invites everyone to help themselves to free food—halal chicken.

Leaving the mosque, Muslet drives to work. That day, he and his two brothers are opening a new clothing store called Krave, located in the city’s humble downtown. Outside, on the street, a chef flips halal burgers and a DJ booms Kodak Black songs out of refrigerator-size speakers, as young men muster under shady awnings, waiting for the doors to open.

A new clothing store is an event in Belle Glade. The closest mall is 35 miles away, and the town’s main commercial strip—a grim mix of storefront churches, pop-up tax refund shops, and dimly lit discount stores—has seen better days. When the Muslet family arrived from Palestine in the 1970s, the area was flush with money from the sugar industry, and the Muslets opened a department store catering to the Jamaican workers shipped in to cut cane. In the early 1990s, the cutting became automated, devastating the local economy. Soon, Belle Glade boasted the nation’s second-highest rate of violent crime. Adjusting to the changing times, the Muslets opened a street-wear boutique called Addiction; Krave, just across the street, specializes in high-end sneakers. Both stores are decorated past the point of functionality, like ornamented temples. Inside Addiction, a giant, two-story trompe-l’oeil mural mimics the wall of a New York City brick tenement, while in Krave, the entire floor has been designed to look like an aubergine-colored cosmos, stippled with stars, planets, and wispy nebulae. Observed from Belle Glade, both realms feel equally distant.

As customers stream into the store, Muslet’s brothers, Faisal and Adam, work the register, while his mother, an octogenarian in a long, black robe, sits in a folding chair by the door, sipping a Coke and worrying a string of prayer beads. Muslet, who has changed out of his thawb into strategically ripped jeans and a white t-shirt bearing the graffitied Krave logo, bounces around the store, tending to customers. A former football player and track star at Glades Central Community High—his nickname was “the Arabian Horse”—he still retains an athlete’s lazy grace. Many of his clientele he has known for years, and he greets them with a brotherly clinch or a dap.

The DJ’s hype man, Charles Askew, tells me he has known Muslet his entire life. He admires the fact that the Muslet brothers always hire in the community, usually from among their customers. A few months before, a Palm Beach County sheriff’s deputy—one of the officers who arrested Muslet—had shot and killed a young black man. Muslet and his brothers had attended a march in the victim’s honor.

“That spoke volumes,” Askew says. “They could sell us clothes, go home to a big old house, not care what’s actually happening here. But they don’t do that.”

I want to ask Muslet more about his case, but every time I try to talk with him, he gets interrupted by requests from customers or employees. At one point, I find him in the back of Addiction, behind a shelf of cargo shorts. He and Wayne Rawlins are kneeling on unfolded polo shirts, murmuring prayers.

Nothing about Muslet suggests a propensity for violence. Nor does he seem to meet Howard’s definition of radicalism. Muslet is both hopelessly American and an asset to his community. He appears to embody everything the United States asks of its immigrants. As an entrepreneurial young man, he co-owned two profitable gas stations in northern Virginia, with his eyes on acquiring more. He wore snakeskin cowboy boots and coached his son’s T-ball team, the Exxon Tigers. Then, in 1999, he and his first wife took a vacation to Myrtle Beach. One sunny afternoon, as Muslet was nudging a rubber inner tube into the water, it dawned on him that he was unprepared for death.

“I suddenly wondered, ‘What if a wave came over me right now?’ ” he recalls. “I was happy, but I wasn’t ready to die, man. So, I said, ‘OK, Allah, just get me back to shore and I’ll live the rest of my life for you.’ ”

Safely delivered, Muslet sat on the sand and thought about all the people who had ever hurt him. He asked Allah to forgive them. Then, he thought of all the blessings—family, money, America—the Almighty had bestowed on him. Finally, he began to think of all the bad things he’d ever done, every person he’d ever wronged, and asked Allah to forgive him. All at once, he was visited by a breathtaking sense of relief. He arose and walked into the ocean, and there, out past the sunbathers and the paddleboarders and the beer-bong enthusiasts, he felt, for the first time in his life, truly clean.

Muslet was not, up to that point, a devout Muslim. He smoked Marlboro Lights and drank cranberry vodka and had once impregnated a woman to whom he was not married. (“Guys who wore robes?” he says. “You know what I used to call them? Taliban.”) After his saltwater baptism, he immediately set about making some changes. For starters, he explained to his wife, who was wearing a bikini, that she was dressed inappropriately. (“They call it a bathing suit,” he says. “But my wife was basically in her underwear.”) Muslet was excited to share his spiritual awakening with his partner, but she didn’t seem to get it. Two days later, on the drive back to Virginia, she asked for a divorce.

When he got home, Muslet took the Koran off his fireplace and began reading it. His taste for alcohol and cigarettes left him. Dressed in a Nike sweat suit and Nautica boots, he got into his Toyota Supra and headed west. For almost 40 days, he drove around the country, reading the Koran at night and giving dawah during the day. Then he moved back to Belle Glade, joined the family business, and became involved in the local Muslim community.

Muslet grew out his beard, adopted the habit of wearing a thawb, and married a woman who loved Islam as much as he did. Then, in 2014, he met Wayne Rawlins. Their bond, Muslet says, was instantaneous. Rawlins had written a book titled America 2064: Islam in America Over the Next 50 Years. For Muslet, it felt like the perfect embodiment of his own philosophy of Islam. “It was the book I had always dreamed of writing,” he says.

America 2064 begins with a short biography of its author. Rawlins, it notes, served as a consultant for the Justice Department on anti-gang initiatives. The FBI once honored him with an award for community leadership. “Rawlins is not a terrorist, extremist, or radicalized fundamentalist,” the bio assures readers. “Nor is he an anarchist or traitor. He is a Muslim born in the USA.”

America 2064 is short—only 208 pages—but its ambitions are enormous. In his preface, Rawlins explains that the book is meant to serve as a kind of blueprint—“a strategic framework to change our country’s political, social, and economic landscape” over the next half-century. All of America’s social problems, he argues—poverty, crime, violence, out-of-wedlock births, pornography, homosexuality—can be solved by applying the Koran. Islam, in his view, is the answer to everything. At one point, Rawlins cites a Republican congressman who denounces Islam as a political and legal system seeking world domination. “He is right!” Rawlins declares. “Islam is intended for all mankind and provides a total way of life.”

Rawlins does not seek to force Islam on anyone. Every individual, he believes, must be free to choose his or her own religion. The way to spread Islam, he believes, is through good deeds. The only weapon is dawah, which is every Muslim’s duty. As more and more Americans convert to Islam, Rawlins hopes, the U.S. Constitution will be amended to reflect the commandments of Allah. In place of our existing system of secular law, Americans would decide to be ruled by Islamic law—sharia. “By 2064,” Rawlins concludes, “Islam will dominate the American landscape, Insha Allah.”

Muslet enthusiastically embraced his friend’s vision for an America united under Allah. After all, Islam had saved his life. Why couldn’t it solve Belle Glade’s problems, too? In 2010, to help bring social services into disadvantaged communities, Rawlins had started a program called Walking One Stop. Today, flanked by activists and community leaders, he and Muslet often go door to door, helping people sign up for unemployment insurance, food stamps, and other public benefits without the hassle of calling on multiple bureaucracies.

“We’re just trying to gain the pleasure of the Almighty,” Rawlins says. “The Walking One Stop is an embodiment of Islam. By doing good deeds with Muslim leadership, it softens the hearts of the people towards Muslims and towards Islam.” He laughs. “It’s just the beginning, though. Yousef and I, we’ve got plans. We want people to become Muslim. There’s a lot of stuff we want to do together.”

Not long before his arrest, the FBI began taking an interest in Muslet. For some years, Muslet had been friendly with a pair of agents from the Miami bureau, who used to drop by the Belle Glade mosque occasionally, to check in. As part of its counterterrorism efforts, the FBI has developed a massive network of confidential informants. The imam who spoke at Muslet’s Friday prayers, Foad Farahi, is currently suing the FBI for trying to deport him after he refused their request to work as an informant. Muslet shows me an email from one of the agents in December 2014, thanking him for passing along his contact information. At the time, Muslet was finishing construction on Krave. “I know you are a leader in your community and someone who we can reach out to,” the email reads. “Hope all goes well with the opening of the new store!”

Then, in the summer of 2015, Muslet flew to Palestine to visit relatives. Not certain how long he wanted to stay, he bought a one-way ticket to Jordan. He was joined by Wayne Rawlins, who wanted to pray in the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem during Ramadan. Seven weeks later, when Muslet flew back into Miami, federal agents were waiting for him at the gate. They took him into a room where he was questioned about his time in the Middle East. Had he really gone to Palestine? Or had he gone into Syria, to meet with ISIS?

Muslet pointed out to the agent that his passport showed that he crossed into Israel two days after arriving in Jordan. Besides, he had posted photos on Facebook of everywhere he visited. Muslet grew angry, explaining that he is a Muslim and that ISIS is not Islam. The beheadings? The stoning? The throwing people off buildings? In Muslet’s understanding of Islam, terrorism and the taking of innocent life is forbidden. Muslet gave the agents dawah. At one point he took a copy of America 2064 out of his bag and passed it to one of the agents. “Read this,” he said. “This is my plan. This is what I plan to do.”

After five hours, the FBI let Muslet go. Two weeks later, though, his brother Faisal was stopped at the Israeli border and refused entrance. He had never been arrested and had no dealings with the FBI. Muslet contacted one of the FBI agents who used to visit the mosque and asked if there was anything he could do. She suggested he come to a meeting at the FBI’s office in Palm Beach. This time, agents asked him about his association with Wayne Rawlins. Muslet again explained about his plan to peacefully Islamicize America. He also made a date to meet them in Belle Glade. He would bring Rawlins, so they could talk to him themselves.

Ever since the September 11 attacks, the FBI has devoted special attention to Palm Beach County. Twelve of the 19 attackers either lived in or had connections to the area. The ringleader, Mohamed Atta, took flight training at Palm Beach County Park Airport. In 2013, the Palm Beach sheriff’s department started Community Partners Against Terrorism, a program designed to encourage residents to report activities they deem suspicious. In a video produced by the department, Sheriff Ric Bradshaw notes that “one person’s observations ... can save thousands of lives.” As an example of suspect activity, the video shows a woman taking a picture of a bridge; suspicious persons are defined as individuals who “just don’t fit in.”

Before meeting the FBI, Muslet and Rawlins arranged to rendezvous at the mosque. When they got there, a Palm Beach sheriff’s car was already parked across the street. As they drove to their meeting spot, a seafood restaurant called Mr. Shrimp’s, they saw sheriffs’ cars dotting the route. A helicopter from the sheriff’s department hovered overhead. At lunch, after Muslet made introductions, he says the FBI asked him and Rawlins if they were interested in working with the bureau.

“We’re working with you right now,” Muslet said. The agents finished their tilapia and left.

Two months later, Muslet was arrested for shaking Howard’s hand.

On the day of the arrest, Muslet’s wife, Nekia, was in the bedroom with one of her children. As soon as she realized what was happening, she ran to put on her head scarf. By the time she got outside, Yousef was being escorted down the street in handcuffs and her mother-in-law was screaming. “I think the officers were worried she was going to pass out,” Nekia recalls. Both women were panicked as they watched Yousef being taken away.

Nekia converted to Islam in high school after being raised in a strict Christian household. “I actually really wanted to fall in love with Christianity,” she says, “but I just couldn’t grasp going through Jesus to talk with God.” Now, as her husband was placed in a patrol car, she told herself it had to be a case of mistaken identity. She gathered her children in the bedroom and explained to them that the police were confused. “I told them that Allah wanted baba to be in jail for the night because he could talk to the people there,” she says. “And that calmed them down.”

Muslet actually knew many of his fellow inmates. Some were customers at Addiction. Greeting him warmly, they hooked him up with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and sheets for his bunk. Muslet, in turn, gave dawah. The next morning, the judge released him on his own recognizance. The threat of a long sentence, though, still loomed.

The evidence that led to Muslet’s arrest was, by any measure, thin. At 12:40 p.m. on December 29, 2015, Hal Howard walked into the sheriff’s office in Belle Glade. According to court records, the dispatcher told the deputy on duty, Kurt Castaldo, that Howard was looking to report “a Muslim that is getting pretty active.” Castaldo sat down with Howard, who told him about the incident with Muslet. At the time, Howard couldn’t recall Muslet’s name—only his address. Castaldo decided to proceed to Muslet’s house to identify the suspect and get a statement. He summoned five deputies, including a canine unit, as backup. He also requested that Howard tag along to identify Muslet. The officers drove off in squad cars, followed by Howard in his truck.

According to Castaldo, when Muslet first answered the door, he seemed friendly and shook hands. But when Castaldo began asking about his encounter with Howard, Muslet grew “belligerent and confrontive.” In a deposition taken three months after the arrest, Castaldo insisted that Muslet kept interrupting him in a hostile tone—“talking over me, not letting me speak.” But another deputy recalled Muslet remaining calm during the questioning. Even when Howard appeared, Muslet seemed more confused than angry. After being told that he was under arrest, however, Muslet lost his temper. One officer said that by the time he “had to go hands on” with the suspect, Muslet was speaking “in his native tongue in a boisterous manner.”

According to Castaldo, Muslet threatened the deputies before he was placed in a squad car. “You guys fucked up now,” he says Muslet shouted. “I am going to get all of you!”

Muslet admits that he exchanged undiplomatic words with the deputy who cuffed him. (“I told him, ‘Man, you need to go get yourself some breakfast or something, because you’re not eating me for breakfast.’ ”) But he denies physically resisting the arrest, or threatening the officers in any way.

Later, at the trial, Castaldo testified that he decided to arrest Muslet because the suspect “had put himself at the scene” of the encounter with Howard. At the moment of the arrest, though, his sole evidence that Muslet had been violent was Howard’s statement. Only after Muslet was placed in jail did Castaldo attempt to corroborate the crime. He contacted Pat Lucey, Howard’s friend who was riding in the truck with him during the incident, and recorded a seven-minute statement about what he witnessed. Then he went back to Howard and recorded a ten-minute statement. No medical examination of Howard was ever conducted, even though Castaldo’s report listed his injuries as “serious.” This—the statements from Howard and Lucey about the incident, and the statement from Muslet about his arrest—comprised the entirety of the Palm Beach sheriff’s investigation into the supposed crime.

It’s not uncommon for law enforcement, erring on the side of public safety, to be hasty in making an arrest. It’s up to the local prosecutor’s office to review the evidence and determine whether it is sufficient to file charges. J.D. Small, the prosecutor who brought the case to trial, says he found Hal Howard’s account “credible,” and that it was corroborated by Pat Lucey.

On the recording, a nervous-sounding Howard offers an account similar—though not identical—to the one he gave me. As Castaldo questions him, he speaks slowly and sounds genuinely shaken. Two moments stand out. At one point, Howard describes the instant he realized that Muslet was Muslim.

“I knew he looked a little weird because I’m not used to a full-face beard,” Howard says. “Then it dawned on me that this is not a Christian. He’s got to be a Muslim. Right then my fear just doubled, because of all the things that are happening in the United States and overseas.”

Later, Howard describes seeing Muslet’s daughter, who was five at the time, on the street in front of his truck.

“And this girl was standing in the middle of the road,” he says. “And I’ll tell you what—I’ve never been scared of an eleven-year-old, twelve-year-old girl, whatever she was, but this girl had evil in her eyes. You could just see it. The hate. And the hair on the back of my neck raised up.”

I ask Small whether these statements—admitting a fear of Muslims and believing a five-year-old girl was evil—made Howard appear less credible to the prosecution.

“I think that’s editorial,” says Mike Edmondson, a department spokesman sitting in on the interview. Whatever Howard’s personal views, he explains, they were irrelevant to the case. Besides, he adds, Howard’s account was backed up by Pat Lucey, who had witnessed the incident.

Listening to Lucey’s short statement, however, this is far from clear. Lucey does confirm some aspects of Howard’s account. He acknowledges that Muslet leaned into the window and was “very loud” and “aggressive,” to the point where the two men felt intimidated. “I guess if we’d said much more, one of us would have got slapped probably, because he was that aggressive,” Lucey says. “I thought he was literally going to come through the window probably.”

But at no point in the statement does Castaldo ask Lucey about a handshake. Nor does Lucey mention one. Lucey, in fact, never clearly describes any kind of physical contact between the two men. The closest he gets is toward the end of the statement, when he offers an ambiguous, fragmentary description of how the encounter ended. Muslet, he says, “finally let go of his hand. Hal pulled back, if I remember right…. I mean, he had his hand…. I thought he was going to shake his hand, but when he started doing the sign language….” Lucey then talks about Muslet performing a gesture in which he spells “Allah” in the folds of his palms. (Muslet later demonstrates this to me, with great pleasure.) Castaldo never asks Lucey to clarify what he means and, a minute later, the recorded statement ends.

Two weeks later, based entirely on this evidence, the prosecutor’s office filed charges.

Muslet’s trial was originally set to be held in early September 2016. But Flynn Bertisch, Muslet’s lead attorney, argued that the proximity to September 11 might put the jury in a prejudicial frame of mind. Ultimately, though, the prosecution and the defense agreed to skip a jury altogether and hold a bench trial, in which a judge hears evidence and renders a verdict.

In his opening argument, Bertisch contended that the case was not really about the handshake at all. “This case,” he said, “is really about God”—how a difference in religious opinion blew up into something much bigger. The state, meanwhile, chose mostly to ignore religion and focus on proving that a genuine assault had taken place. Small, the prosecutor, called Pat Lucey to the stand as his first witness.

A bald, bespectacled man with an endearingly bubbly disposition, Lucey didn’t offer much to support the state’s case. After Muslet began talking about Islam, he testified, he basically ignored him, seeing any argument as hopeless.

“I just kind of tuned him out,” said Lucey, who is partially deaf. “I felt like he has his point of view and I have mine. Maybe all his french fries wasn’t lining up in his Happy Meal.”

As for a handshake, Lucey testified, he simply didn’t see one. Asked for more details about what he did see, Lucey confirmed that Muslet was gesturing expressively and touched Howard on the arm a few times while he was leaning in the window. Asked whether this seemed like assault, Lucey equivocated.

“Did I see a belligerent pulling of him?” he responded. “No.”

What stayed with Lucey most about the encounter was the avidity with which Muslet sought to convince them of the rightness of Islam.

“The man was zealous about what he believes,” Lucey said. “He’d make a good Baptist evangelist.”

Next, the state showed a video of Muslet in the backseat of the squad car after his arrest, clearly agitated. At this point, Muslet did not know why, precisely, he was being taken to jail. When told he was being charged with battery and “burglary of a conveyance,” Muslet was incredulous.

“Battery?” he sputters. “Where? Where, brother?”

“Based on the statement by the victim,” a deputy replies.

“Who’s the victim?”

“Hal.”

“Mr. Hal? I touched Mr. Hal? I offered to shake Mr. Hal’s hand!”

As a deputy tries to calm him down, Muslet, his voice increasingly loud and strident, begins rambling.

“You can’t charge me with that because you have no proof of that! He is a liar! I have witnesses! There were a hundred witnesses! A thousand witnesses! Burglary? What do you mean burglary? How do you come up with this bogus charge? What, do you think I’m ignorant? I have rights! You have no right to have me in this car right now! Because you have no—show me the evidence that you have! Other than some lying, crazy Islamophobic.” For the next 20 minutes, Muslet cycles rapidly through confusion, righteous anger, respectful deference, and threats of a lawsuit. “I’m a Palestinian, wears a rag on his head,” he continues, “wears a thawb, I mention Allah—Allah’s the name of the almighty creator, Allahu Akbar—that’s his name. And you don’t even know his name. What’s God’s name? Walking around, taking orders, shooting people. Who’s in charge?” At one point, Muslet denounces the sheriff’s deputies as “a bunch of Islamophobic racists.”

Watching this in court, the judge chuckled. “I’m going to teach a class,” he said. “What not to do if you’re arrested.”

The last person to testify was Hal Howard. He sat with his hands folded neatly in his lap, hunched slightly forward, like someone in church. His account of the confrontation with Muslet differed, in certain key details, from the version he gave me, as well as from the one he first offered Deputy Castaldo. Now, instead of Muslet shaking him with his right hand, Muslet used his left hand to grab him by the wrist. Instead of Howard having to pry their hands apart, Muslet let go on his own. Instead of Muslet leading his children silently into the house, Muslet told them, “Get out of the road before he kills you.” Despite all the inconsistencies, Howard seemed to genuinely believe his own account of events. He again said—somewhat touchingly—that Lucey would corroborate his version of events.

The prosecution, for its part, tried to avoid any mention of religion. But the topic kept working its way into the trial. At one point, Small asked Howard why the conversation with Muslet had scared him.

“Well, I’m a Christian, number one,” Howard replied. “I believe Jesus Christ died for my sins. And I have a father in heaven. And none of them has even a nickname called Allah.”

Small quickly tried to steer the line of questioning back on course. “But what was it about the, uh, defendant’s demeanor—”

“I felt like he was trying to force Allah onto me,” Howard interrupted. “He wanted to come to my church and teach everybody about Allah.”

The defense, by contrast, sought out this angle wherever it could find it. Toward the end of questioning, Bertisch noted that Lucey had wished Muslet a merry Christmas.

Howard nodded. “God-blessed him, too.”

“Did you find that weird?”

“No. He’s American. Ninety percent of us believe in God. What’s wrong with saying God bless you? It’s on the dollar bill.”

“But you have an individual here who believes in a different god, correct?”

“I don’t know what he believes in,” Howard said. “I guess it’s a god.”

“Well, he told you he wanted to come to church to enlighten people about his god.”

“I don’t know about ‘enlightening’ anything.”

“You just thought,” Bertisch ventured, “he was going to force his god on you?”

“After he got through talking, yes,” Howard says. “That’s what I thought he wanted.”

In the course of his testimony, Howard comes across as both deeply averse to being preached at by a Muslim and committed to doing what he thinks is the right thing. At one point, he repeats that it was his sons and friends who urged him to report the handshake. But he also notes that he was inspired, in part, by a public service announcement he saw on television.

“I told them,” Howard said, referring to the sheriff’s office, “what I heard on the TV, about the FBI saying that no matter how small it is, you got to report it.”

The judge interjected. “So, when you say, ‘You should report things,’ was it, you know, he was an Arab or Muslim or something?”

“Anything suspicious,” Howard said. “When that—I guess it was the bombing or the killing down in California—they said those people had seen them supplying bullets and stuff. And anything you see that’s suspicious, or anything that happens suspicious, should be reported.”

After further questioning, it became apparent that Howard was referring to the mass shooting that took place on December 2, 2015, when a Muslim couple killed 14 people at an office Christmas party in San Bernardino, California. The shooting had occurred less than three weeks before Howard encountered Muslet after the Christmas party at his pastor’s house. Reporting Muslet was his way of trying to prevent such things from happening in Belle Glade.

“That’s the only way we’re going to find out what’s going on,” he told the court.

During the trial, it was hard not to see Muslet and Howard as spiritual twins. Their faith followed similar, classical lines. Both are men who, lost in sin, had undergone a sudden, unexpected conversion—delivered from doubt into what William James called a “state of assurance.” They remain devout in their faith, live self-denying lives, and believe that the end times are upon us. Two men in dying towns, residents of a burning world, had found a path to eternal life. When they met, their disagreement struck at the very center of who they are.

There was no evidence to suggest that Hal Howard was lying. He clearly believed that something violent had been done to him. And, in one sense, something had. Whatever the handshake had been like, Muslet had, consciously or not, taken a jackhammer to the bedrock of another man’s identity. Such a gesture, though conceived with peaceful intentions, could not have failed to feel threatening.

The question of what, precisely, happened between Howard and Muslet can’t be answered with any certainty. But what came afterward was clearly shaped in large part by the wider political battle being waged over Islam. It’s possible that Muslet’s religious beliefs played no role in his prosecution. But in Palm Beach—once the training ground for the September 11 attackers, now a center for anti-Islamic hate groups—Howard’s account was deemed more plausible than Muslet’s. Though uncorroborated by any evidence, Howard’s version of events seemed correct to police and prosecutors, enough to pursue a case to trial and force a local businessman and civic activist to consider, for almost a year, the possibility that he would be taken away from his family and placed in prison for the rest of his life.

In his ruling on the case, Judge Peter Evans made clear that his ability to render a verdict was hindered by a lack of clear evidence. “There was no investigation” he said. “I mean, what investigation? They went and talked to a couple guys.” He then ruminated aloud for several minutes about how best to weigh the need of law enforcement to protect public safety with the rights of citizens not to be the target of undue suspicion.

“It’s unfortunately the society that we live in,” the judge said. “A little nothing turns into a case where I’m supposed to convict this guy and send him to prison for life. Because he shook a guy’s hand too hard? I don’t know. Since 9/11, every time there’s an incident involving a Muslim, everyone’s on red alert. But there’s incidents every day.” The judge sighed. “How do you deal with this stuff? Right? All kidding aside, to me, this is really just sort of a fascinating societal issue. Because I see it every day in here. So how do you deal with it? On the one hand, you have the government, saying ‘Hey, you see any Muslim do something, you should report it,’ because, you know?”

At the same time, the judge said, Muslet should be slow to call people bigots.

“Instead of Mr. Muslet, for example, talking about ‘This is racism, you’re picking on me’—doesn’t there have to be some kind of understanding on the other side? These cops—well, maybe this isn’t the best example of a great investigation—but what are the cops doing? They’re doing their job. It’s their job to go arrest someone on a felony. Whether they should have or not is another issue. But they do what they do.”

The judge turned to Muslet, sitting in his thawb. “Meanwhile, he’s screaming, what? Islamo—”

“Islamophobia,” Muslet said.

“Islamophobia! So, yeah, it’s kinda got to go both ways, right? I don’t know.” The judge threw up his arms. “Good luck solving this one!” In the matter of the criminal case, though, he declared Muslet innocent.

Muslet, overcome, stood up.

“Can I—can I shake your hand, judge?”

There was an awkward silence, then laughter in the courtroom. The judge looked uncertain. Finally, he motioned to his judicial robes. “Well, we’re both wearing dresses,” he said.

Muslet was deeply relieved at his acquittal. He claims, however, never to have been in doubt about the outcome. “Allah wouldn’t do that to me,” he says. Then he pauses. “Unless, of course, that was what he wanted. But I don’t think it was.”

Not long after the trial, Muslet stopped by the home of Dr. Kaki, Hal Howard’s beloved physician. The two men hail from the same village in Palestine, and have known each other for years. “I told him ‘Hey, one of your patients tried to put me away for life,’ ” says Muslet. “He was pretty surprised.”

Just before I leave Belle Glade, Muslet gives me a tour of the town. He shows me where, on the main street, he wants to install a storefront mosque, to call the Muslim shopkeepers to prayer, and where he wants to open a halal restaurant. Farther out, we pass the leviathan sugar mill, its stacks spewing white smoke. In the distance, poppy-yellow crop dusters buzz the fields. The streets are dotted with campaign signs for Muslet’s opponent for city commissioner. Muslet hasn’t had time to put up any signs of his own, but he remains optimistic about the election.

“I think people are ready to take on Big Sugar,” he says. “The sugar companies, they’ve been making millions for years, and what do we get back?” He is quiet for a while, staring out the window. “I just wanna see people come up, man. Live good lives.”

When we reach Muslet’s house, his kids are playing in the backyard. His wife smiles and waves. Muslet points at the roof of the home of Howard’s pastor, Eric Stevenson. On the apex sits a big, plastic nativity scene. Muslet’s kids and the pastor’s kids play together, but the two men aren’t friends. Shortly after the pastor moved in, he threw a lawn party whose guests included young teenagers.

“The girls are wearing these short shorts and there are young men out there, too,” Muslet frowns. “And they’re doing things like kissing and—intimate things.”

During the party, Muslet walked over to Stevenson’s house. “I said, ‘Hey Eric, I wanna ask you a question….’ He said, ‘Yeah?’ I said, ‘Eric, what’s your God’s name?’ ” The conversation followed a predictable trajectory. It strikes me that giving dawah seems to be something Muslet does when he feels annoyed.

“Everyone gets dawah—Muslim, Jew, Christian, police, FBI,” Muslet says. “It’s what I do.”

I ask Muslet whether he understands why people who are used to a secular form of government might be alarmed at the prospect of sharia.

“I understand separating church from state, and I agree with it,” he says. “Separating mosque from state? I agree with that. But you can’t separate God from state, because God is a way of life. I don’t have a choice. I really don’t. I can’t force anyone to be Muslim, but it’s my obligation to share it with people. Now, will sharia law ever be—.” He stops. “Actually, it is going to be implemented, because Allah is gonna implement it. Eventually. I want the Messiah to come, to confirm to the people. I’m ready for him, because he’s the one they’re going to believe. Everything that’s happened, all the signs. He’s coming back.”

A few weeks after I leave Florida, the election for commissioner is held. Muslet receives 124 ballots, or approximately 12 percent of the vote. He calls it “a valuable learning experience.” His plans to Islamicize America with Wayne Rawlins remained undiminished.

Howard was disappointed at the verdict. “I didn’t expect them to send him to prison or nothing, but I thought they’d find him guilty,” he tells me. “Because he was guilty.” Howard isn’t worried about his own safety, however. “I don’t think God would let him hurt me.”

A month later, Howard felt severe chest pains. When he visited Dr. Kaki, the physician told Howard to go to the emergency room, immediately. When he arrived, doctors discovered a clogged artery in his neck. A three-inch stent was placed in his carotid artery. He credits Dr. Kaki with saving him from a stroke.

“I love that man,” he says. “I truly do.”