On July 15, 2015, Amazon marked the twentieth anniversary of its founding with a “global shopping event” called Prime Day. Over the next 24 hours, starting at midnight, the company offered special discounts every ten minutes to the 44 million users of Amazon Prime, its members-only benefit program. The event was astonishingly successful: Amazon made 34 million Prime sales that day, nearly 20 percent more than it had on Black Friday, the traditional post-Thanksgiving buying bonanza. The company received almost 400 orders per second—all on a single, ordinary day in the middle of summer.

Prime Day is now an annual event; last year it marked the largest sales day in Amazon’s history. The sale has become a secular holiday, akin in its economic wallop and social ubiquity to Super Bowl Sunday or the Fourth of July. Today, nearly half of the nation’s households are enrolled in Prime. That’s more Americans than go to church every month. More than own a gun. And more than voted for either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton last November.

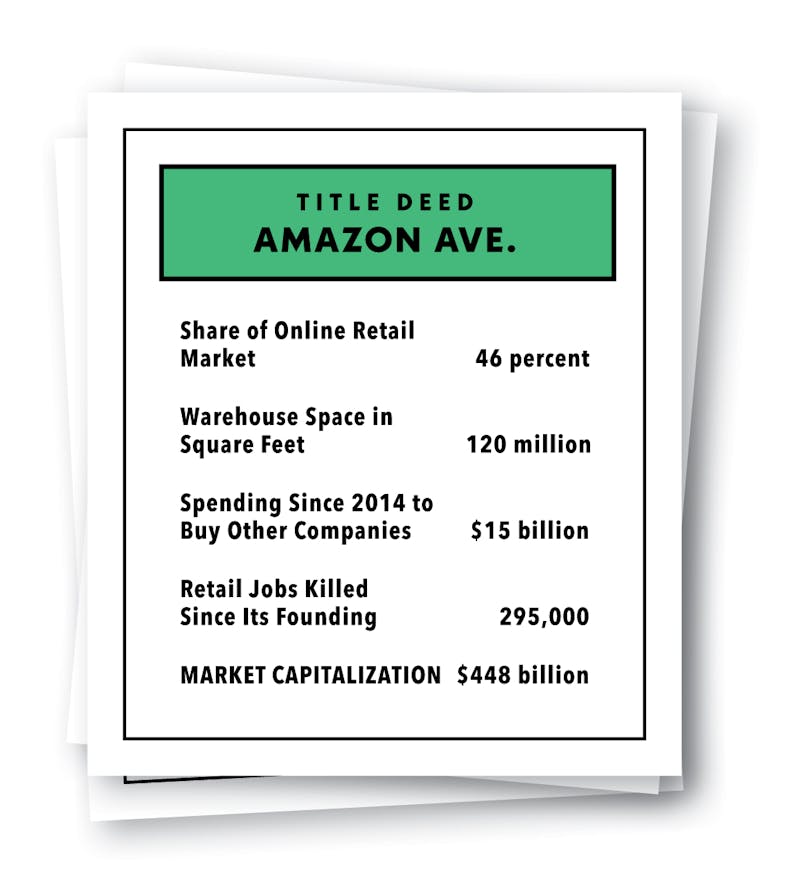

The rise of Amazon, and its overwhelming market dominance, has accelerated the collapse of traditional retail outlets. Amazon’s stock has risen by 300 percent since 2012, and Wall Street analysts have compiled a “Death by Amazon” index to track the retail companies most likely to be killed off by the online giant. This year alone, three retail stalwarts—Walmart, JCPenney, and Rite Aid—plan to shutter or sell off nearly 1,200 stores, and nearly 90,000 Americans have been thrown out of work since October. One of every eleven jobs is tied to shopping centers, which generate $151 billion in sales taxes each year. All of which is rapidly being lost to a single company. In June, Amazon announced its largest-ever acquisition, paying $13.4 billion to buy the Whole Foods grocery chain. Such is the power of the “everything store” and its “one-click ordering.”

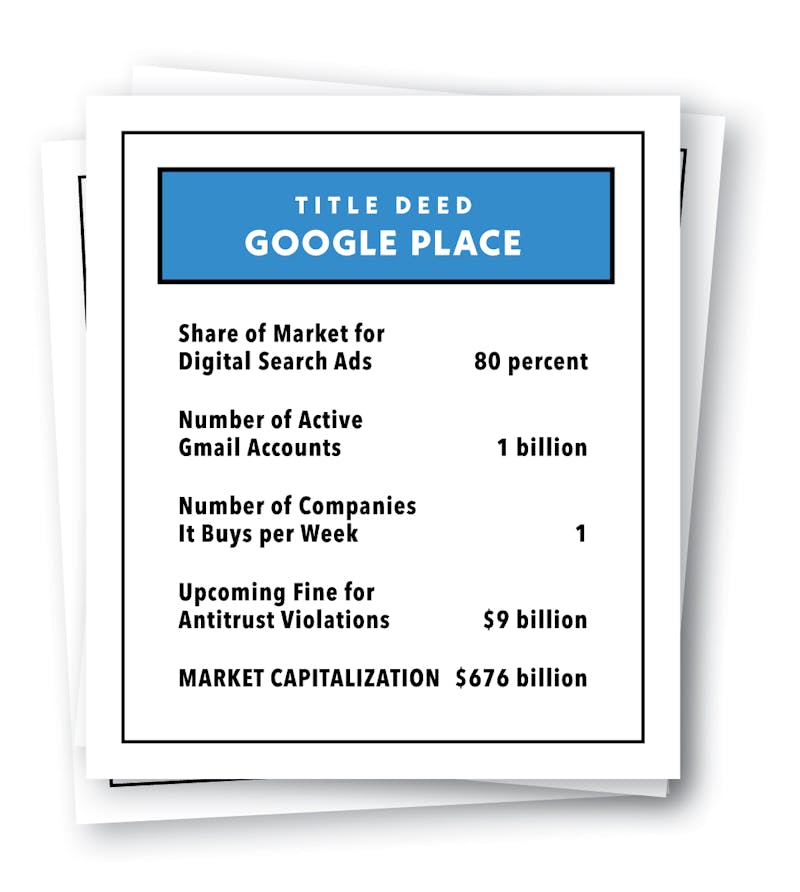

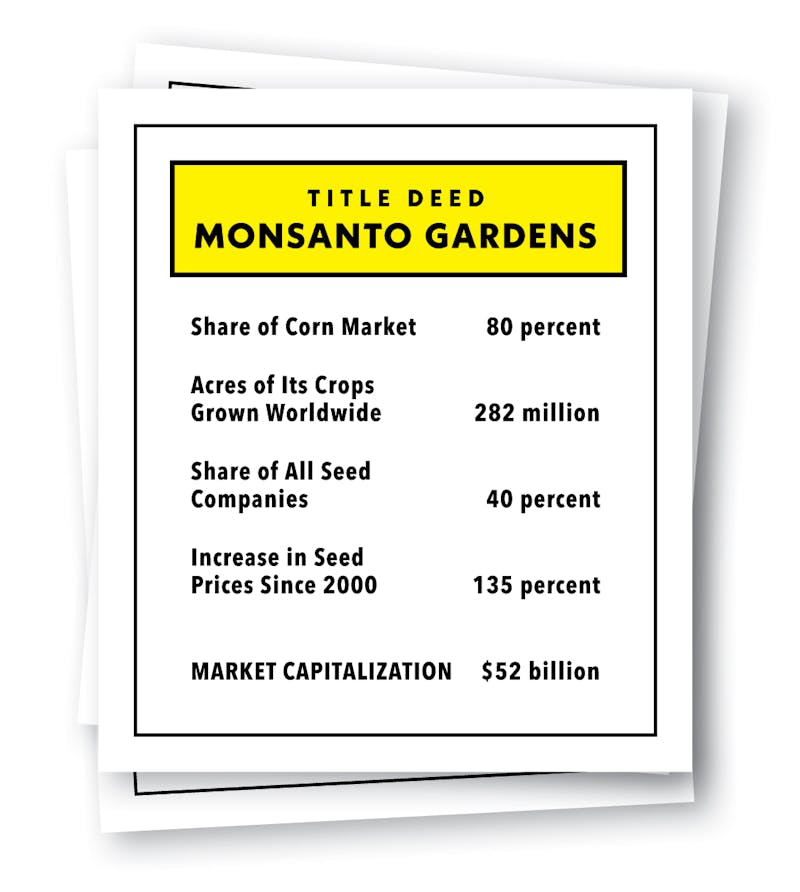

Amazon did not come to dominate the way we shop because of its technology. It did so because we let it. Over the past three decades, the U.S. government has permitted corporate giants to take over an ever-increasing share of the economy. Monopoly—the ultimate enemy of free-market competition—now pervades every corner of American life: every transaction we make, every product we consume, every news story we read, every piece of data we download. Eighty percent of seats on airplanes are sold by just four airlines. CVS and Walgreens have a virtual lock on the drugstore and pharmacy business. A private equity firm in Brazil controls roughly half of the U.S. beer market. The chemical giant Monsanto is able to dictate when and how farmers plant its seeds. Google and Facebook control nearly 75 percent of the $73 billion market in digital advertising. Most communities have one cable company to choose from, one provider of electricity, one gas company. Economic power, in fact, is more concentrated than ever: According to a study published earlier this year, half of all publicly traded companies have disappeared over the past four decades.

Monopoly can sometimes seem like a good thing. When Walmart first began to take over the retail industry, for example, Americans embraced its “everyday low prices.” Mom-and-pop stores on Main Street may have been going out of business, but the savings at the new Walmart were just too good to resist.

But the lower prices offered by monopolies come at a steep cost. A corporate giant like Amazon is able to use its economic advantage to eliminate jobs, drive down wages, dictate favorable terms to its suppliers, and even set the price the postal service is permitted to charge for the privilege of delivering its packages. In 2012, Amazon bought a robotics company that automates warehouse labor, and then blocked its competitors from using the technology. If robots are going to take all our jobs, Amazon wants to make sure it owns all the robots.

Then there’s the way Amazon exploits the conflicts of interest inherent in its business model. Writing in the Yale Law Journal in January, policy analyst Lina Khan recounts the case of an independent merchant who used Amazon to sell Pillow Pets, a line of pillows modeled on NFL mascots. Sales were booming—until the merchant noticed that Amazon had begun offering the exact same product on its own, right before the holidays. Undercut by Amazon, which gave its own Pillow Pets featured placement on the site, the merchant’s sales plummeted. Khan calls this “the antitrust paradox.” As one merchant observed, “You can’t really be a high-volume seller online without being on Amazon, but sellers are very aware of the fact that Amazon is also their primary competitor.”

Increasing concentration of ownership has also led to unprecedented levels of corporate crime. In case after case, courts in Europe and the United States have ruled that giant companies are operating as “cartels,” engaging in illegal conspiracies among themselves to divide up their turf. As a result, they have been able to fix the price of almost everything in the economy: antibiotics and other life-saving medication, fees on credit card transactions, essential commodities like cell-phone batteries and electric cables and auto parts, the rates companies pay to exchange foreign currency, even the interest rates on the municipal bonds that cities and towns rely on to build schools and libraries and nursing homes. A single price-fixing scandal by the world’s largest banks—fixing the global interest rates known as LIBOR—involved more than $500 trillion in financial instruments.

But the price we pay for increasing monopolization goes far beyond such corporate rip-offs. Monopoly increases income inequality by concentrating wealth in major cities: St. Louis, for example, has lost a long roster of hometown companies to mergers and acquisitions, including Anheuser-Busch, TWA, Ralston Purina, May Department Stores, A.G. Edwards, and Panera Bread. Rural America has been especially hard hit, as local stores and family farms have been “disrupted” by giant supermarket chains, seed companies, fertilizer giants, meat processors, and grain traders. And don’t blame automation: Corporate America’s investments in workplace technology have plunged by 30 percent over the past 30 years. Even robots are subject to the power of monopoly.

What drives monopolization is not business know-how or technological innovation, but public policy—a political environment that permits or even enables an investor like Jeff Bezos to engage in a massive accumulation of economic power. Not that long ago in America, no company as large and destructive as Amazon would have been allowed to exist. Preventing and breaking up such corporate behemoths, in fact, was at the very center of the Democratic Party’s agenda. “Private monopolies are indefensible and intolerable,” the party’s platform declared in 1900. “They are the most efficient means yet devised for appropriating the fruits of industry to the benefit of the few at the expense of the many.”

In the late 1970s, however, the Democrats began to abandon the idea that big is bad. Over the past four decades, the party has stood by as giant supermarket chains replaced local grocery stores and Too Big to Fail banks replaced local lenders. As monopolies broke up unions and drove down wages, Democrats increasingly came to rely on campaign contributions from the very corporations that were consolidating their control over the American economy. The Obama administration, like the Bush administration before it, declined to bring a single major monopolization suit against U.S. companies. Even The Washington Post, that exemplar of political opposition to Donald Trump, is now owned by Jeff Bezos. Dissent, brought to you by monopolists.

But with Republicans in control of all three branches of government, and with the big business ethos espoused by Hillary Clinton in tatters, Democrats may finally be returning to their anti-monopoly roots. Leaders within the party are once again looking to the aggressive antitrust movement launched during the Progressive era and extended through the New Deal, which propelled America into three of its greatest decades of rising prosperity and economic equality. The question now is: Can Democrats find a way to rechannel the popular outrage unleashed by Trump, and to repurpose the party’s traditional opposition to monopoly in the age of Amazon?

Democrats scored their first major victory against corporate monopolies during the presidential election of 1912. That year, two candidates ran on platforms that called for placing major restrictions on companies that attempted to dominate the market and thwart competition. Teddy Roosevelt, running on the third-party “Bull Moose” ticket, believed that monopolies were inevitable and in some ways even virtuous, and that the government should simply oversee them to make sure they operated in the public interest. Woodrow Wilson, the Democrat, took a different approach: He argued that monopolies are a fundamental threat to political liberty, and that the government should attack and disperse them to protect democracy from the corrupting influence of economic concentration. After his election, Wilson went on to lay the foundation for the government’s anti-monopoly apparatus. He established federal oversight of corporate mergers, set up the Federal Reserve System to rein in Wall Street, and created the Federal Trade Commission to protect free commerce from anti-competitive business practices. Most important of all, perhaps, he placed Louis Brandeis on the Supreme Court.

Brandeis, who had cemented his reputation as “the people’s lawyer” during his six-year crusade to prevent banker J.P. Morgan from monopolizing New England’s railroads, was the chief intellectual architect of the New Deal. In 1933, just days after Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated, Brandeis issued a stirring dissent in Liggett v. Lee, which struck down a Florida law designed to protect local businesses from out-of-state chains. Reading from the bench, Brandeis blamed the Great Depression on “the gross inequality in the distribution of wealth and income which giant corporations have fostered.” The government, he argued, had the right to regulate the “concentration of wealth and power” if it threatened the public welfare. Antitrust, as Brandeis saw it, wasn’t about protecting consumers—it was a way to safeguard democracy.

At the time, Brandeis was incredibly influential as a public intellectual; a reissue of his 1914 book, Other People’s Money, which detailed how “trusts” were harming the economy, had become a best-seller. He not only influenced FDR, who had swept into the White House on a wave of anti-monopoly sentiment, he placed his disciples within the administration. Roosevelt’s coalition combined both Brandeisians and Bull Moosers, who waged a fierce intraparty battle over how Democrats should manage the economy. During the first years of the New Deal, the Bull Moose side held sway and even suspended many of the existing antitrust laws. But starting in 1935, with the Second New Deal, Brandeis’s faction gained the upper hand and began to take apart the centralized power of corporate monopolies. The Robinson-Patman Act protected local retailers from the onslaught of chain stores such as A&P, the Walmart of its time, while the Glass-Steagall Act prevented Wall Street from gambling with other people’s money.

Democrats also unleashed the largest and most aggressive wave of antitrust prosecution in American history. Thurman Arnold, FDR’s head of antitrust enforcement, cracked down on some of the country’s biggest corporations and trade associations, from General Motors and Alcoa to the American Medical Association and the Associated Press, which were engaged in price fixing and other anti-competitive activities. Rather than railing against monopoly in political terms, Arnold was careful to present himself as an impartial “cop on the beat,” a nonpartisan prosecutor using the courts to defend the bedrock American principle of economic competition. By 1942, he was widely considered the most popular figure of the New Deal, alongside J. Edgar Hoover.

The anti-monopoly principle that Arnold and Brandeis established—the idea that economic power should be decentralized and spread into many hands—became the basis of a new social contract. For the next three decades, the federal government largely permitted big business only in segments of the economy that required scale and technical know-how, such as cars, chemicals, and steel. Labor unions made sure that workers were treated fairly, while stores, farms, and banks remained relatively small and under local control. The government also prevented electric utilities, phone companies, airlines, and other “natural monopolies” from diversifying into other businesses, and forced them to offer everyone the same services at the same price. Productivity boomed, and America entered a golden age of egalitarian prosperity, with a large and expanding middle class.

By the late 1960s, however, the social contract had come under attack from both the right and the left. At the University of Chicago, the emerging group of conservative thinkers known as the Chicago School, which produced economists and lawyers such as Milton Friedman, George Stigler, and Robert Bork, rebelled against what they perceived as the socialism of the New Deal. What was needed, they argued, was less government intervention in the marketplace. In 1982, spurred by the theories of Friedman and Bork, Ronald Reagan gutted the federal government’s enforcement of antitrust laws, unleashing a massive merger boom in everything from airlines, retail, and oil to packaged goods and manufacturing.

Scholars on the left had also begun to question the antitrust achievements of the New Deal. The historian Richard Hofstadter argued that the anti-monopoly faction of the Democratic Party grew out of the “status anxiety” of the working class, paving the way for McCarthyism. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith, meanwhile, theorized that big labor and big government provided a “countervailing power” against the excesses of big business. His analysis of A&P, the monopoly supermarket chain broken up by Brandeis and the New Dealers, argued that large, concentrated businesses are actually good for consumers because they drive down prices—the same argument made today in support of Amazon. “New Democrats” like Gary Hart, Paul Tsongas, Michael Dukakis, and Bill Clinton moved the party even further from its anti-monopoly roots, embracing concentration, which supposedly offered efficiency and low prices, as a boon to the economy.

In 1992, Clinton removed antitrust language from the Democratic platform and began bashing bank regulators. Once in office, he gutted anti-monopoly restrictions on broadcasters, laying the groundwork for the media concentration that brought us Fox News and Rush Limbaugh. He touched off an unprecedented wave of consolidation in the defense industry; since Clinton took office, the number of “prime” defense contractors has plummeted from 300 to only five. He also repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, which had been erected during the New Deal to separate big banks and investment firms, and moved power into shadow markets free from regulation. The result was the worldwide economic collapse of 2008, brought on by the megabanks and insurance giants created in the wake of the repeal of Glass-Steagall.

Barack Obama, who took office at the height of the financial crisis, was presented with a historic opportunity to reassert the government’s role in preventing and breaking up dangerous monopolies. Instead he argued that the megabanks that Democrats had unleashed on the marketplace were now so central to the economy that they could never be dismantled. Such thinking indicates just how far Democrats have retreated from the trust-busting days of Brandeis, who authored an influential book called The Curse of Bigness. In the view of centrists like Obama, bigness is no longer a menace to society—it’s essential to the efficient functioning of the entire economy.

Under Obama, the Justice Department prosecuted only one banker involved in the collapse of the financial system, opting instead for negotiated settlements and inconsequential fines. Federal regulators likewise stood by and did nothing as corporate giants like Facebook and Google and Amazon asserted a staggering level of control over America’s digital platforms. Even Obama’s signature policy wound up increasing concentration: The Affordable Care Act kicked off a wave of consolidation among hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and health insurers. Since 2008, there have been more than $10 trillion in mergers, as corporate giants went on a consolidation spree to buy up competitors and expand their dominance in the marketplace. In 2015, the year before Trump was elected, America set a record for the most mergers in a year.

The Democratic Party’s about-face on monopolies wasn’t just bad for citizens and communities—it led to the disintegration of the party itself. In 1994, two years into Bill Clinton’s first term, Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives, which it had held more or less continuously since 1930. Today, Republicans not only control all three branches of the federal government, they also hold majorities in 32 state legislatures, along with the governorships of 33 states. As monopolization has returned in full force, the Democrats now hold less power at the state and local level than they have at any point since the 1920s—the very decade that sparked the rise of the chain store and the onset of the Great Depression. By turning their back on the Progressive-era philosophy of Brandeis and his fellow reformers, Democrats have effectively rendered themselves indistinguishable from pro-business Republicans. “Today, while liberals and conservatives may argue about the size and scope of the federal government,” anti-monopoly activist Stacy Mitchell has observed, “support for breaking up and dispersing economic power finds expression in neither of the major parties.”

In May, Democrats gathered for an “ideas conference” at the Center for American Progress in Washington, D.C. The daylong event was widely seen as the first audition for 2020, as prominent Democrats lined up to try out for the lead role of presidential candidate. But when Senator Elizabeth Warren stepped up to give the conference’s keynote address, she delivered an antitrust speech that would have been right at home at a meeting of FDR’s brain trust. “We can crack down on anti-competitive mergers and existing monopolies,” Warren assured the approving crowd. “We can break up the big banks.”

It was unusually direct language, even for such a liberal gathering. For the first time in nearly half a century, Democrats appear poised to restore monopoly power to the center of their agenda. Beginning with Occupy Wall Street and the populist campaign of Bernie Sanders, and accelerating since the wave of nationalist victories from Brexit to Donald Trump, Democrats are undergoing a generational shift in how they understand the economy, away from the pro-trust accommodations of the Clinton-Obama years and toward the Brandeisian interventions that preceded them.

Warren is now the leader of the emerging Brandeisian wing of the Democratic Party. In 2015, she called for reimposing Glass-Steagall, the powerful anti-monopoly law passed during the New Deal to separate investment and commercial banking. In a speech last year, she directly criticized her party’s pro-monopoly stance. “Some people argue that concentration can be good, because big profits encourage competitors to get into the game,” she said. “This is the perfect stand-on-your-head-and-the-world-looks-great argument. The truth is pretty basic—markets need competition, now.” Since then, Warren has co-sponsored a bill to bypass the monopoly on hearing aids by making them available over the counter, sought greater transparency in fees charged by airlines, and worked to block the proposed merger of Time Warner and AT&T.

Other Democrats are also leading the charge against monopolies. Senator Al Franken has used his seat on the Judiciary Committee to help block the Comcast–Time Warner merger, and has sought to restrict conflicts of interest in the credit-rating industry. Three Democratic congressmen—Ro Khanna, Rick Nolan, and Mark Pocan—are setting up a caucus to focus on questions of monopoly. And a new family-farm group led by Joe Maxwell, the former lieutenant governor of Missouri, is being organized to take on rural monopolies like Monsanto and meat-processing giant JBS. Even moderate Democrats are being forced to recognize the threat posed by monopoly. “The American people intuitively understand that there’s too much concentration in this country,” Senator Amy Klobuchar, the ranking Democrat on the antitrust subcommittee, declared in March. “Tackling concentrations of power is a linchpin to a healthy economy and democracy.” So far, though, Klobuchar has offered only a few modest reforms that would help federal regulators better analyze proposed mergers and acquisitions.

In the current climate, Democrats oppose antitrust measures at their own peril. During a recent debate over the budget resolution, Klobuchar and Bernie Sanders introduced a proposal to allow the importation of prescription drugs, a measure designed to introduce competition into the pharmaceutical marketplace and reduce prices. Several Democrats, including Senator Cory Booker, worked with the Republicans to vote the measure down. Grassroots reformers responded by sending out email alerts, and Booker was deluged by comments from angry voters. A month later, Booker and Sanders proposed a joint bill to allow prescription drug imports.

Even big business itself is rising up against the monopolistic power wielded by the Big Three: Google, Facebook, and Amazon. All three companies profit from the anti-competitive nature of their business models. Google and Facebook not only control massive content empires, they own the large advertising networks that monetize that content. Amazon is simultaneously a giant retailer, a marketplace for other retailers, and a producer of goods and services. It charges different people different prices for the same items, and it manipulates what gets shown to users through control of the Buy button on its site. So the Big Three’s rivals are starting to fight back. Yelp has accused Google of stealing its content to build a local search site, then manipulating search results to direct users there. News Corp recently accused Google of creating a “dysfunctional and socially destructive” environment for journalism by profiting from fake news. Oracle is financing a Google Transparency Project to expose the company’s political influence.

What is emerging, slowly but surely, is a new agenda—one that could once again make tackling the power of monopolies a core component of what it means to be a Democrat. Americans recognize that corporate consolidation doesn’t just undercut freedom in the marketplace—it undercuts the economic equality and free flow of information on which our political system depends. “If we will not endure a king as a political power,” Senator John Sherman argued in 1890, advocating for the antitrust law that bears his name, “we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessaries of life. If we would not submit to an emperor, we should not submit to an autocrat of trade.” Unchecked monopoly power, in short, is simply not compatible with democracy.

To succeed at breaking up today’s economic overlords, Democrats must pursue three related approaches to antitrust. First, they must stop monopoly before it happens. That means using the antitrust authority of the federal government to crack down on mergers. “Monopoly is made by acquisition,” notes Jonathan Taplin, the author of Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy. “Google buying AdMob and DoubleClick, Facebook buying Instagram and WhatsApp, Amazon buying, to name just a few, Audible, Twitch, Zappos, and Alexa. At a minimum, these companies should not be allowed to acquire other major firms, like Spotify or Snapchat.” When it comes to stopping mergers and acquisitions, Democrats should become far more aggressive.

Second, Democrats should work to rebuild structural barriers to monopoly in a wide range of industries, as they did in the 1930s with Glass-Steagall in banking. A content distributor like AT&T should not be allowed to buy a content provider like Time Warner. Online ad companies should be barred from owning browsers and ad blockers. And Amazon should not operate as both a marketplace and a competitor within that marketplace. It’s one thing, say, to run a big trucking company—but if you’re allowed to own the highway itself, other truckers won’t stand a chance.

Third, Democrats should move to split up or neutralize the power of corporations that have the ability to dominate and control entire realms of commerce. Amazon has forced publishers to offer it steep discounts on books, Monsanto is organizing the genetics behind much of our food supply, and the Cleveland Clinic exerts power over doctors throughout northeast Ohio. Such monopolies must either be regulated aggressively or broken up.

What is most needed is a new way of understanding how our political economy works, and for whom. Democrats, at last, are beginning to see the need to aggressively restructure the marketplace and decentralize both economic and political power. To win elections on an anti-monopoly platform, however, the party must abandon its penchant for technocratic prescriptions and frame its new agenda in broadly inspirational terms. Here again, they should take a page from Brandeis and the reformers of the Progressive era, who couched their opposition to monopoly in terms of economic common sense and bedrock American values, like competition and community and democracy. To oppose monopoly, by definition, is to support an independent citizenry against financial autocracy—and few things are more American than that. Antitrust means protecting the family farm from Monsanto, free speech from Facebook, the community from Citibank.

Economic power, as Supreme Court Justice William Douglas observed in a 1948 landmark case against Big Steel, “should be scattered into many hands so that the fortune of the people will not be dependent on the whim or caprice, the political prejudices, the emotional stability of a few self-appointed men.” The philosophy of antitrust, he explained, “is founded on a theory of hostility to the concentration in private hands of power so great that only a government of the people should have it.” As the Trump presidency, a government of the minority, implodes in scandals of its own making, those who voted for him will join the millions of other Americans searching for genuine solutions to the political chaos and economic inequality that is fueled by corporate monopolies. This is the challenge facing the Democratic Party. The goal is not just to oust Trump, but to address the dangerous concentrations of power that drove so many citizens to vote for him in the first place.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the number of major U.S. health insurers had decreased from five to three in 2015. The Justice Department blocked the mergers the following year. The article has also been amended to clarify John Kenneth Galbraith’s theory of monopoly power.