Ever since Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign in 2015, critics worried about his authoritarian tendencies. He’s done much to justify those fears. At his rallies, he whipped crowds into such a frenzy that protesters were beaten. As president, he’s flouted elementary rules about nepotism and conflict of interest; undermined the independence of the judiciary by impugning judges overseeing cases involving him or his administration; obstructed justice by firing James Comey after he refused to pledge loyalty to him; and arbitrarily limited media access by, for instance, replacing daily White House press briefings with off-camera gaggles where recording is banned.

Trump’s presidency is already starting to resemble the one imagined by David Frum in his March article for The Atlantic, “How to Build an Autocracy,” where he described a global “democratic recession” in terms that intentionally evoked Trump:

Worldwide, the number of democratic states has diminished. Within many of the remaining democracies, the quality of governance has deteriorated.... What is spreading today is repressive kleptocracy, led by rulers motivated by greed rather than by the deranged idealism of Hitler or Stalin or Mao. Such rulers rely less on terror and more on rule-twisting, the manipulation of information, and the co-optation of elites.

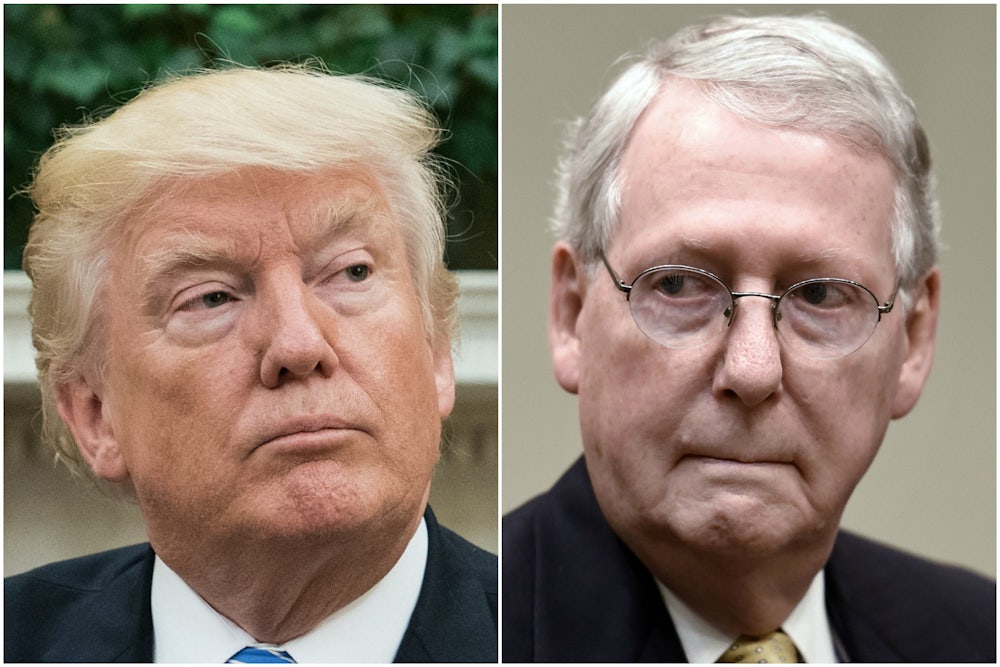

By Frum’s definition, Trump is indeed an aspiring autocrat. But he’s only one wing of the anti-democratic trend in American politics—in the Republican Party, to be specific. Equally dangerous, and intimately connected with Trump’s mode of authoritarianism, is the degradation of democratic norms in the Senate under Mitch McConnell. The majority leader and a dozen other senators—all of them male—wrote their Obamacare repeal bill in secret, concealed not only from the public and Democrats, but even their Republican colleagues. Now, having finally released his version of the American Health Care Act on Sunday, McConnell is trying to force the bill through the Senate as quickly as possible. A vote is expected next week, meaning the public and press have only a few days to pore through the 142-page document—and even fewer days to digest the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis, which is expected on Monday or Tuesday.

Compare this with the Democrats’ legislative approach to the Affordable Care Act. Republicans have long lied that Democrats rammed Obamacare into law, when in truth, as The New York Times reported this week, there were “months of debate that included more than 20 hearings, at least 100 hours of committee meetings and markups, more than 130 amendments considered and at least 79 roll-call votes.” On the Pod Save America, a podcast hosted by four former aides to President Barack Obama, Dan Pfeiffer articulated how McConnell’s approach imperils democracy:

This is not how the process is supposed to work. What you sort of realize in watching how Trump has conducted himself [and] in how Mitch McConnell has conducted himself is that [the] functioning democratic process as we know it is not embodied in law or in the Constitution. It depends on both parties ... believing in a set of democratic norms about the value of public input, about the value of transparency, about allowing the public to have a say in what’s happening. And if one of those parties ... decides to disavow all those norms, we get to a place where ... this is not American democracy. We basically have an election and live in a quasi-authoritarian state until the next election.

Trump’s authoritarianism and McConnell’s are two very different strains. The president is a narcissist who gathers power for personal gain self-gratification. He cares little for the specifics of policy outcomes, and merely wants victories that he can boast about. For instance, on Friday morning he tweeted—

I've helped pass and signed 38 Legislative Bills, mostly with no Democratic support, and gotten rid of massive amounts of regulations. Nice!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 23, 2017

—and then appeared on Fox and Friends to make the patently false claim, “I’ve done in five months what other people haven’t done in years.” Constant displays of alpha-male dominance is also central to Trump’s brand of authoritarianism. He taunted his GOP rivals during the Republican primary, and since then has mocked his Democratic foes—first Hillary Clinton, and now Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer. This week, he tweeted that the House and Senate minority leaders, respectively, were doing the Republicans a favor by remaining in charge, the implication being that they’re ineffective if not incompetent.

I certainly hope the Democrats do not force Nancy P out. That would be very bad for the Republican Party - and please let Cryin' Chuck stay!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 22, 2017

This is the authoritarianism of pure spectacle. McConnell, by contrast, is withdrawn and diffident in his public. (He’s jokingly likened to a turtle because of his appearance, but behaves like one, too.) While the majority leader doesn’t crave attention, he does care deeply about a specific policy agenda: advancing the plutocratic preferences of the Republican party’s donor class. Infinitely more knowledgeable than Trump about how government functions, McConnell subverts norms with a laser-like focus on advancing that agenda. His authoritarianism, in other words, is one of procedure.

As different as they are, these two forms of authoritarianism depend on each other. It’s unlikely that the Republican Party would have won a unified government last fall without Trump’s theatrical flair. To judge not only by last year’s election, but also this week’s special congressional election in Georgia, Trump’s tribalist politics have far more appeal with the Republican base than a forthright agenda of tax cuts for the rich and entitlement cuts to the poor. And when it comes to that agenda, all that really matters is that the policies be sold through the lens of negative partisanship. After all, Trump campaigned on a promise not to cut Medicaid, whereas McConnell’s version of the AHCA would slash the program by hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade. But Trump easily resolves such dissonance by reminding his supporters of the real enemy here: Obamacare.

I am very supportive of the Senate #HealthcareBill. Look forward to making it really special! Remember, ObamaCare is dead.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 22, 2017

If the Republican Party needs Trump, the president is equally dependent on the GOP. Given his manifest disinterest in policy and the details of governance, he would be unable to pass anything without crafty leaders like McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan. But there is a more sinister dimension to Trump’s alliance with these Republican leaders: Congress has the power to check the president, including impeachment and removal if necessary. Ryan and McConnell are the bulwarks protecting Trump from a wide range of areas where he should be held accountable. If they wanted to, they could push for laws requiring him to reveal his taxes, force him to place his assets in a blind trust, and use nepotism rules to limit the power of family members, among a range of other checks.

Republicans in the House and Senate have implicitly made a devil’s bargain with Trump, giving him a free hand to indulge his kleptocratic and autocratic tendencies in exchange for what they want: stalwart conservative judges for the Supreme Court, and a presidential signature on whatever bills Ryan and McConnell manage to pass. And make no mistake: He will sign any major legislation that crosses his desk.

In theory, Trump could reject a health care bill from Congress on the grounds that it would violate his campaign promises to protect Medicaid and “to have insurance for everybody.” He’s reportedly grumbled in private that the House bill, which closely matched the Senate’s, is “mean.” But that should not raise the hopes of Obamacare’s defenders. A presidential veto, or even the threat of one to lessen the cruelty of the AHCA, is out of the question. Reveling in his emerging kleptocracy, Trump is smart enough to know that he has to stay on Ryan and McConnell’s good side if he wants to hold on to the presidency.

Trump also wants his second big “win” as president, after the confirmation of Justice Neil Gorsuch. Consider how he bathed in imagined glory after the Senate confirmed his Supreme Court pick. “We are here to celebrate history,” he said. “I have always heard, the most important thing that a President does is appoint people, hopefully great people, like this appointment, to the United States Supreme Court. And I can say, this is a great honor.” He added, “And I got it done in the first 100 days. That’s even nice. You think that is easy?”

Consider, also, the Rose Garden celebration Trump threw for House Republicans after they passed their health care bill—the one he would later call “mean.” He described Ryan as a “genius,” and left little doubt that he would treat McConnell and Senate Republicans exactly the same if they accomplished the same feat: “It’s going to be an unbelievable victory when we get it through the Senate, and there’s so much spirit there.” Rest assured, Trump is already wetting his pants in anticipation of a second Rose Garden bash, and of an eventual Oval Office photo op where he can scratch his electrocardiographic signature on a bill condemning millions of Americans to poorer health.

Frum wrote in The Atlantic that the repressive future he imagines under our authoritarian president “is possible only if many people other than Donald Trump agree to permit it. It can all be stopped, if individual citizens and public officials make the right choices.” Alas, our public officials—the ones who control all of the levers in Washington, anyway—are making the wrong choices, by cynically enabling the president. Mere months since Frum’s essay, the war against American democracy is now being fought on two fronts: Trump’s autocratic assault on the presidency, and McConnell’s dismantling of democratic norms in the Senate. But the two fronts are part of the same ultimate struggle; these two men are the authoritarian twins, and it’s up to the final bulwark—individual citizens—to stop them.