How many buildings have been designed but never built? Countless cities, whole extra urban universes. Every time a sketch or a blueprint is scrunched up and thrown in the bin, it’s like a wrecking crew has razed it. But in the ghostworld of imaginary structures, every unbuilt building stands.

A new show at the Museum of Modern Art collects the drawings (and a few three-dimensional objects) from the archive of Frank Lloyd Wright—the architect with the best brand-name recognition in America—on the occasion of his 150th birthday. Being a celebrity, however, did not guarantee that Wright’s visions would be built. The show is full of gorgeous places that never came into existence. Strange houses, buildings designed around hexagonal units and arranged on the diagonal.

Wright designed 532 buildings that were made, and about the same number again that never were. His career spanned seven decades. His personal life was beset by chaos. He left his first wife Kittie, then in 1914 his partner Mamah Cheney was murdered alongside six other people by a domestic worker named Julian Carlton. His second wife, Miriam Noel, was a hopeless morphine addict. His third marriage, to Olgivanna, seems to have been all right. Wright famously said that, “not only do I fully intend to be the greatest architect who has yet lived, but fully intend to be the greatest architect who will ever live.” Walking around this show, a beautiful edifice built of the flotsam and jetsam of a long career, one realizes that even a man like that didn’t always get his way.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, Wright made three houses that defined his “organic style”—Graycliff, Tallesin West, and Fallingwater. Wright’s ideas about organic form are among his most influential legacies. He began using the word “organic” as early as 1908, although he never really articulated it into a slogan (as his mentor Louis Sullivan had done with his own mantra, “form follows function”).

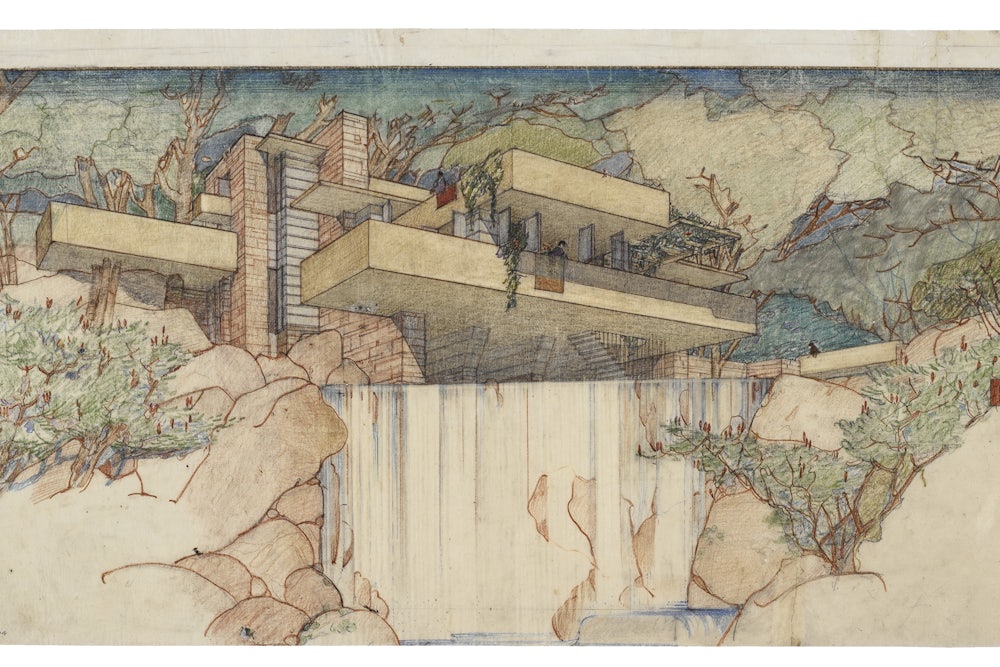

Fallingwater, also known as the Kaufman Residence, is Wright’s most famous work and probably the model of organic architecture that lingers closest to the front of the American imagination. The principle of organic architecture is simple, commanding its followers to sympathetic and congruous relations between the structure and the environment in which it is built.

The building is daringly cantilevered, with reinforced concrete balconies shooting off in multiple directions over the water flowing beneath it. The underside of them is naturally a pretty humid spot, and Fallingwater has become very moldy at times. In fact, the whole building resembles a fungus, one of those tough ones that grow out horizontally from a tree like a stubborn little shelf. (Kaufman himself nicknamed the building “Rising Mildew” because of the mold and the leakiness.)

This principle of integration with the landscape carries over into Wright’s visions for ideal cities, which are characterized, to quote a MoMA wall text, by an “urbanism of dispersal or decentralization made possible by new forms of transportation.” Although midcentury concrete of the Wright style has come to signify the plantless, dense urbanism of the city, drawings from The Plan for Greater Baghdad Project and for the Rosenwald School (both exhibited at length here) show a more sensitive, greener vision.

On a much smaller level, this show also emphasizes Wright’s interest in ornamentation. This work is surprisingly colorful, bold, even Kandinsky-esque (Wright liked orange). One of the show’s most interesting galleries focuses on Wright’s work on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He designed the building roughly in the shape of the hotel’s logo, an H with an I cutting through it. The Imperial Hotel pieces in this exhibition include a number of decorative terracotta blocks, as well as upholstery textiles and furniture.

The building suffered greatly from a series of earthquakes. After the Great Kantō earthquake on September 1, 1923, Wright received a telegram from Baron Kihachiro Okura testifying to its endurance. It read: “Hotel stands undamaged as a monument of your genius hundreds of homeless provided by perfectly maintained service congratulations.” However, this was not quite true. It had been damaged, and the hotel also gradually fell into disrepair. In 1967 it was destroyed and rebuilt.

Four hundred and fifty pieces make for a big exhibition, and this one takes a while to walk around. There are architectural drawings, of course, but also models, film clips, textiles, photographs, bits and bobs. The show is in twelve themed sections and MoMA says that it is “structured as an anthology rather than a comprehensive, monographic presentation.”

When I visited the show, by far the most crowded room contained nothing but a large, projected clip of Frank Lloyd Wright on What’s My Line? The clip reiterated the obvious, that Frank Lloyd Wright was and remains a very famous man indeed.

But if Fallingwater is a big celebrity place you should “see before you die,” like the Taj Mahal or the Parthenon, MoMA’s exhibition draws attention to the careful, quiet labor of the studio. In placing many medium-sized drawings at eye height through a number of rooms, without much fanfare, this exhibition creates a tribute to the unrealized.

To preserve a drawing of a place that never had a chance to exist is to treasure the quality of an idea over the beauty of its actual form, the way that it looks once made flesh. That act of preservation is also a tribute to the mind that had those visions, rather than the works that remain in the world. But where exactly is the line between the mind and the work of an architect? If that line exists, it is in the difference between two and three dimensions, or perhaps in the translation of scale that comes between model and construction. The line may exist in multiple ways and in multiple forms, criss-crossing like the floor-plan of a house built to hang over a river.