You can still watch him die on YouTube. Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti—who rose from provincial obscurity to dominate his country and wage war across the Middle East, becoming the scourge of three American presidents, ally to another, and, finally, the most prominent casualty of the war on terror—ascends the gallows. He’s surrounded by men in masks, some of whom heckle him with Shiite slogans. Using a surprising degree of care, a man places a black scarf around his neck. A noose is thrown around the scarf and cinched tight. Saddam yells at the crowd, “Do you consider this bravery?” Someone tells him to go to hell. “The hell that is Iraq?” he retorts. He begins to recite the Shahada, the Islamic profession of faith, when a door opens beneath him, and he falls, snapping his neck.

It’s here, at the moment of his death, that the videos usually lose him. The camera goes suddenly askew and the sound is washed out with celebratory shouts. Later, the picture settles on his face, his body cloaked in shadow.

What you can’t see in these videos is what happened afterward. As Saddam’s body was taken out of the execution chamber, a feverish crowd began to beat and spit on him. Nearby, a dozen-odd American soldiers looked on, and rather than joining in the crowd’s exultation, they shared a feeling of sadness, followed by outrage. One soldier was so incensed that he launched himself toward the crowd, only to be held back by one of his colleagues.

Perhaps this is the most shocking thing about Saddam Hussein’s 2006 death: that the American soldiers who guarded him in his last weeks genuinely grieved for him. These details emerge in The Prisoner in His Palace, a new book by Will Bardenwerper, a former infantry officer and Pentagon employee. “I feel like I let him down,” Specialist Adam Rogerson told Bardenwerper. It was as if he had lost a family member. “I almost feel like a murderer, like I killed a guy I was close to.”

Such feelings seem to be widely shared among the young men who guarded Saddam Hussein up until the moment of his execution. Some of them spent months chatting, playing chess, and smoking cigars with a genial old man who bore no resemblance to the vicious dictator of Axis of Evil lore, on trial for crimes against humanity. Several of the Super Twelve, as they came to call themselves, genuinely liked their prisoner and experienced post-traumatic stress after his death. For one young soldier, Saddam’s body was the first corpse he had ever seen. Steve Hutchison “sometimes wakes up with a jolt during the night, expecting to see Saddam.” Robert “Doc” Ellis, an Army nurse from St. Louis, later reflected, “I know I should hate Saddam, but it’s not easy.”

That a retinue of guards could grieve for their prisoner reflects the strange alchemy that can develop in such a peculiarly intimate situation. The American soldiers who guarded him were practically sequestered. They were forbidden from talking about their work and spent most of their time either in the former palace where Saddam’s jail cell was constructed or the heavily guarded courthouse that hosted his trial. Furthermore, Saddam had survived for more than 30 years as Iraq’s president through intimidation, cunning, and occasional bursts of charm, and so he made for an unusual prisoner. Recognizing that his true enemy was George W. Bush, Saddam cooperated with his guards. He asked them about their families and girlfriends and wrote poems for them. They joked and swapped stories, and the guards eventually became taken with the old man, who seemed to adapt well to his reduced conditions. Several of them even cleaned up a derelict room in the palace and turned it into an office for Saddam, who spent hours reading, conducting correspondence, and writing in his diaries.

Saddam’s literary side is often overlooked—an understandable omission when discussing someone responsible for horrific massacres—but it speaks to his divided character. He may have been capable of monstrous acts, but he could also resemble an eminently normal person, albeit one who was as likely to give a favored official a new Mercedes as send him off to prison. By 2003, the man who loved Dostoevsky and Naguib Mahfouz had removed himself from the daily affairs of state. When the Americans invaded—a decision that baffled Saddam, who thought he could be an ally to the West in the war on terrorism—he had just sent off his latest novel for critiques to Tariq Aziz, his foreign minister and close adviser. After he was captured, Saddam frequently requested reading and writing materials. “You must understand, I am a writer,” he told John Nixon, a CIA interrogator whose book, Debriefing the President, was published last year. “And what you are doing by depriving me of pen and paper amounts to human rights abuse!”

It seems unbelievable that the man who had executed thousands, who had stood approvingly by as his commanders ravaged Kurdish communities with chemical weapons, could say this. The irony is so thick that it can only be sustained by someone with a deliberate moral blindness, the kind necessary for any dictator who keeps his people living in perpetual fear of violence. Saddam saw himself as a fearsome, benevolent sovereign, a cultured and far-sighted man, despite having left his native country only twice and repeatedly plunging his people into disastrous wars. In his eyes, no other Arab leader was his equal, and it was essential that his words be preserved for the sake of history, which would hold him, hundreds of years from now, in the sort of esteem that he felt for the 12th-century sultan Saladin, another great warrior from Tikrit.

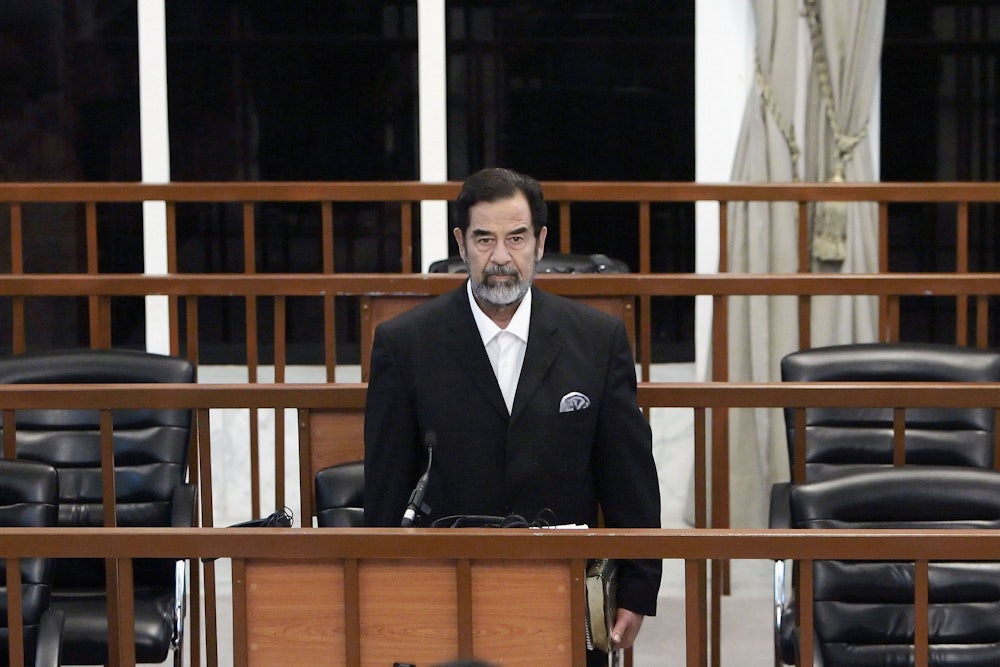

By the time that Saddam passed through CIA interrogation and landed under the care of the Super Twelve, his bombast was largely reserved for his public trial, where cameras could capture him yelling at the judge and decrying the proceedings as illegitimate. Ever the performer, Saddam oscillated between denying knowledge of atrocities that occurred under his rule and proclaiming his own omnipotence. “Not a single plane can fly without my order,” he shouted during his lawyer’s closing presentation.

One soldier in Bardenwerper’s book compares him to a caged lion. When Saddam slept, “he looked majestic and peaceful, but if you removed the glass, you’d see a different animal.” To others, he possessed a grandfatherly beneficence. They hardly bothered to close the gate to his cell, knowing that escape was impossible, despite the insurgency that they could hear raging nearby. Ellis, the nurse, confided in Saddam when his brother died. “I will be your brother,” Saddam replied, offering Ellis a hug. To another soldier, Saddam promised that he would pay for his college education—provided that he could one day get access to his funds.

For Saddam, these promises weren’t so fanciful. He often spoke to his guards as if he would one day be in charge again. He had been sentenced to death before, he told them, and he had survived. He thought that the country needed him and that the insurgency was a natural result of his removal from power. You’ll miss me soon enough, he told his interrogators. Here he’s in agreement with some American analysts, including Nixon, the former CIA officer. Nixon came to see Saddam as a brutal but clever operator who, through manipulation and fear, maintained unity in his fractious country. “From 1990 to 2003 Washington worked to undermine and destroy Saddam without understanding the potential consequences,” Nixon writes. “Our leaders seem unable to put themselves in the shoes of foreign leaders, particularly authoritarians.”

Crediting Saddam with preserving the integrity of Iraq is far different from absolving him, but at times the two get confused. Neocon defenders of the Iraq War point to Saddam’s brutality and claim that the region is better off without him, that his removal may have even precipitated the Arab Spring. Neither of these points stands up to much scrutiny. But the possibility of removing Saddam, which had been considered by presidents going back to Reagan, became all but certain in the jingoistic days after 9/11. (The American public was already primed, having spent the 1990s periodically bombing Iraq and imposing severe sanctions, leading to hundreds of thousands of Iraqi deaths.)

The question of whether we had the right to do any of this, much less the ability to shepherd a peaceful occupation, was never properly considered. Fourteen years later, litigating the invasion—the most disastrous foreign policy decision since the Vietnam War—has largely become a matter of criticizing de-Ba’athification, the disbanding of the army, and other second-order issues. The sober establishment consensus maintains that we may have made some mistakes, but it’s incumbent upon us to remain and clean up our mess, which now takes the form of the campaign against the Islamic State.

Saddam saw a protracted insurgency as inevitable. “The occupier who comes across the Tigris to our country and asks the occupied to stop fighting—that is not logical,” he told Nixon. “We will say, ‘If you want to stop the bloodshed, you should leave.’ You will be losing nothing by leaving, but we will be losing everything if we stop fighting.”

Flip Saddam’s parallelism around and you get where we are today. We have stayed, and the bloodshed hasn’t ceased. We have lost so much, and the Iraqis even more. But why expect any change? The U.S. has spent decades intervening in Iraq without understanding Iraq or its leaders. These books about the mercurial Saddam’s last days show how far we still have to go.