Consider the myth of the regular guy politician. He’s an outsider. He gets results precisely because he doesn’t understand the point of ordinary political entanglements—of lobbyists, polls, or slick consultants. He speaks his mind and his mind is always on the interests of regular guy Americans who are just like him.

We know this figure from American films and television. There are a heap of comedies in this genre, most of them made in that post-Cold War, pre-9/11 period when people started to get really sick of politicians, but the stakes were relatively low. Bulworth, Man of the Year, Head of State, My Fellow Americans, The Distinguished Gentleman, Dave—in these movies, regular guys become politicians, or politicians become regular guys, and everything magically turns out well. The problem with politics, these films argue, is politicians. And if we just got them out of the way, America would be fine.

Well, now we have our first regular guy president. Donald Trump may have been a billionaire reality television star before he was elected, but he shares many of the regular guy politician’s attributes. What he and Bulworth and Mays Gilliam and Dave have in common is the idea that keeping it real—speaking your mind freely, without calculating self-censorship—is what makes a good president. We have learned the hard way that it is not.

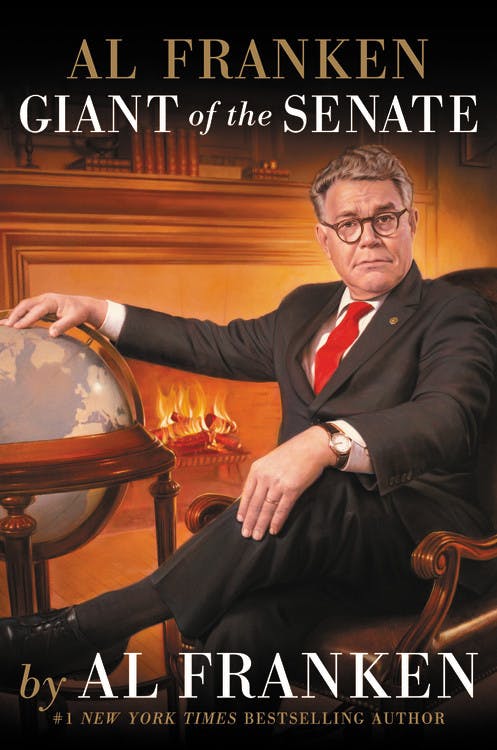

But there is hope yet for regular guy politics—maybe you just need the right guy. Senator Al Franken’s political memoir Al Franken, Giant of the Senate does what so many outsider politicians have failed to do: It demystifies politics while making a surprisingly strong—and surprisingly moving—case on behalf of political engagement. Partly masquerading as a satire of the political memoir (easily the worst genre publishing has to offer), it’s a clear-eyed look at how things work in Washington and, most importantly, how frustrating it is when they don’t. It’s also funny, the surest sign that Franken may actually be a regular person.

Franken’s first two books, Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot (1996) and Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them (2003), were prescient critiques of unhinged right-wingers and the mass media that amplified their message. Rush Limbaugh, like Franken’s Indecision 1992 Comedy Central special, predated The Daily Show both in its tone and style: snide and smart, with an emphasis on digging through archives for damning material. Franken was a trailblazer on the left, and it’s surprising that publishers didn’t turn his style of satire into a cottage industry, the way that conservative publishers bankrolled their operations with books about how the Clintons were murderers and Barack Obama was an illegal alien usurper. These were accessible, funny books about how things really work—and, deep down, how they should work.

Al Franken, Giant of the Senate comes from this lineage. Its premise is that Franken’s job prevents him from saying what he really thinks and describing just how fucked we really are. (Citing Senate decorum, Franken refrains from cursing until the final sentence of his book.) The memoir is a way of stepping outside the Senate’s rules to finally tell the truth. The arc is of Franken finding his voice, first as a child in Minnesota, then on Saturday Night Live as a writer and performer; then losing it, as a politician whose jokes are decontextualized and weaponized by his opponents; then finding it again in the pages of the book you are holding in your hands.

In political memoirs, the most insufferable part is the beginning, where valuable political lessons are learned at a young age, often from a wise family member. Franken seems singularly embarrassed by this convention and he rushes through his formative years. (There is nevertheless a lot of talk of bootstraps, but that is, to the best of my knowledge, a legal requirement for books by politicians.) Almost the entirety of Giant of the Senate’s breezy 416 pages is about his political career, which kicks off on page 64. Franken’s first Senate campaign in Minnesota in 2008—which ended in a six-month long recount and a historically narrow margin of victory—takes up the next 130 pages.

Normally this would be a very troubling sign, hours of reading about bean feeds (they’re important political events in Minnesota). But Franken’s first campaign is fascinating. It’s about the incredible indignities of running for office, which are only tempered by the connections he makes with voters and the dedicated staffers who work to get him elected.

Franken’s anger at the way his comedy career was treated has clearly not abated, nor has his dislike for his opponent Norm Coleman. (In a footnote, Franken notes that Coleman still serves the people of Minnesota—as a paid lobbyist for Saudi Arabia.) Some of the best writing in Giant of the Senate is about the DeHumorizer™, what Franken called the Coleman campaign’s ability to take his writing totally out of context, whether it be “Porn-o-Rama,” a Playboy piece he wrote about the future of sex, or a rape joke he told in the SNL writers room that ended up in New York magazine.

Franken’s still smoldering anger is revelatory in that it’s an indictment of our bad politics. Ultimately, after many, many months on the campaign trail, Franken learned that age-old political cliche, “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.” Nevertheless, explaining is exactly what any non-politician would do in these moments, and Franken’s depiction of slowly learning to bury his sense of humor shows just how dehumanizing a life in politics can be. Giant of the Senate comes across sometimes as a therapeutic exercise, a way to unload baggage he’s carried since he entered politics in 2007.

Franken’s career in the Senate is given a similar treatment. He is very good at the shifting scope of the Senate—it is simultaneously a very big body, with thousands of employees and lobbyists jockeying for attention, and a very small one, where he technically has only 99 colleagues. Franken is openly admiring of many of them, particularly Amy Klobuchar, Harry Reid, and the Chucks, Grassley and Schumer. Franken also writes about his friendship with Jeff Sessions, which is kind of weird, but says he’s proud to have voted against his appointment as attorney general. To his abundant credit, though, he is very mean about those he dislikes. Having to apologize to Mitch McConnell for rudeness is depicted as a career low. (Franken blames McConnell for most of the upper chamber’s dysfunction.) And Franken’s treatment of Ted Cruz, which has already been much-discussed online, is a truly great addition to the ever-growing body of literature about how much Ted Cruz sucks. “I like Ted Cruz more than most of my other colleagues like Ted Cruz,” he writes. “And I hate Ted Cruz.” (A bit about workshopping a joke about Cruz with Klobuchar and Cruz himself is one of the book’s highlights.)

There’s a lot in the book about the big moments in politics: elections, debates, inaugurations, when a bill becomes a law. But its best moments are more banal ones. Calling rich people for money is treated as a circle of hell. Franken constantly has to invent new routines—and entertaining songs to sing to himself—to keep his sanity. An impromptu round of dancing at an Indian reservation (Franken proudly serves on the Indian Affairs Committee), against the wishes of his staff, is an entertaining look at real-life politicking.

Contrary to some of his fans’ expectations, Giant of the Senate does not work as a prelude to a presidential run. Franken’s take on what Democrats should stand for is easily the weakest part of the book—his politics are solid, but it’s the rare time he sounds like a politician. Franken has always been better writing about Republicans than Democrats and Giant of the Senate is no different.

Perhaps the best part involves an actual piece of legislation: a bill to fund a three-year study that would pair service dogs with veterans and analyze the results. The bill eventually passed but the three-year study is still going on nine years later. And the veteran who inspired it, who became a friend of Franken’s, took his own life. As Franken writes, it’s “a story about politics at its best: I met a heroic American who gave me a good idea, I reached out to experts to craft legislation, I found bipartisan support, and we got it done. Nobody lied about it, or sank it with a poison pill, or hired sleazy lobbyists to stop it from becoming law. But this is also a story about how even when everything goes right, politics can be full of setbacks and frustrations.”

So much of the regular guy politician narrative is about finding easy answers to complex problems. Giant of the Senate, in contrast, is a book about coming to terms with complexity without being overcome by it. He sees the Senate’s dysfunction through the same eyes everyone else does, and, unlike many of his colleagues, openly admits that it’s dysfunctional. This only makes his clear affection for the institution more endearing. Maybe more of his Senate colleagues should tell jokes. Just not Ted Cruz.