In 1980, the conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady created an alter ego and named her Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire. She wore a dress composed of 180 pairs of white gloves and carried a white cat-o-nine tails constructed of sail rope and white chrysanthemums, as she invaded various art museums and galleries around New York City. When O’Grady’s character entered a room, she would throw down her whip and shout out poems with forceful lines such as “Black art must take more risks!” and “Now is the time for an invasion!” Other times, she would beat herself with her delicately constructed whip, a pointed demonstration of her oppression as a black person in America. Her dress of white gloves communicated the inward oppression of middle class black women understandably desperate for respect.

Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire, French for Miss Black Bourgeoisie, was a performance piece located at the intersection of race, class, and gender. “In that era,” O’Grady said, “even though black feminists may have admired the energy, even the delirium, of white feminist rhetoric, not to mention the bravery of many of its actions, they still felt alienated by and even a bit derisive toward it.” She represented an imagined reality, a world filled with women like herself—black, maybe middle class, and bold. Photographs of her 1981 performance, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Goes to the New Museum, show O’Grady strutting down an empty corridor, on her way to infiltrate another exclusive art space. She wears a wide grin, typical of a beauty pageant winner. But her eyes hint at a different, more radical agenda: Every performance reflected her determination to create space and visibility for black women in a movement—and more broadly a world—that, at that point, preferred to remain exclusive and blind.

This effort to make visible the experiences of black women also lies at the center of the Brooklyn Museum’s new exhibition We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-1985. Focusing on the work of more than 40 black women artists from the second-wave feminist movement, the exhibition recognizes the work of these artists committed to activism at a time of intense social change. From Emma Amos to Lorraine O’Grady and Lorna Simpson, these women created work addressing issues at the intersection of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movement, the Anti-War Movement, the Gay Liberation Movement, and the Women’s Movement. We Wanted A Revolution offers a rare look at this moment in time, placing the history of these black women artists and activists at the center of a historical narrative rarely told from their perspective.

But the exhibition’s resonance with our political moment also makes it a resource for understanding feminism now. The activism of the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements have prompted many to become more socially conscious about issues of class- or race-based privilege. Civic engagement in opposition to Trump has also required conversations about the conditions of those most affected by destructive policies. With that the narratives and experiences of black women have adopted a new glow, a particular sheen bestowed upon those who become culturally relevant. Yet these conversations, which are most critical to maturing the definition and understanding of feminism, are diluted and remain exclusive to a particular, “woke” type of white woman, often overlooking real inclusion altogether.

We Wanted A Revolution presents an expansive vision of an ideal feminist society: Faith Ringgold’s “For the Women’s House,” a vast mural the artist painted for the Women’s House of Detention in Riker’s Island. The mural has eight scenes, each showing a woman at the center of various tasks. One scene shows a black female doctor from the Rosa Parks Hospital teaching a class on drug rehabilitation. Another shows a woman officiating a wedding and the mother of the bride giving her daughter away. Another scene depicts a blonde white woman, whom Ringgold later identified as a lower class woman in her fifties, driving a bus. In the far right corner is the image of a young white woman with her black son reading from a book with quotes from Coretta Scott King and Rosa Parks.

It is a mural about a world where women of all races and classes are respected and considered. Each scene occupies an eighth of the mural, communicating a deeper sense of equality. Whether a doctor or a bus driver, each woman is a vital part of the fabric of humanity. In an interview with her daughter Michelle Wallace, Ringgold recounted what the female inmates told her they wanted to see: “They said they wanted to see justice, freedom, a groovy mural on peace .. .the rehabilitation of all prisoners, all races of people holding hands with god in the middle, 85 percent black and Puerto Rico, but they didn’t want whites excluded. There was a kind of universality expressed by their feelings.”

Unfortunately, this universality did not extend both ways: It has been nearly 50 years since the height of the second-wave feminist movement. While the movement must undoubtedly be credited for increased rights and protections for women, it often failed to include the interests of poor, non-white, non-cisgendered women. In 1971, Toni Morrison wrote an essay for The New York Times Magazine titled, “What the Black Woman Thinks About Women’s Lib.” In it she considers why black women are reluctant to join arms with a movement whose narrative has been shaped by the work of Betty Friedan and her book, The Feminine Mystique. “What do black women feel about Women’s Lib?” she asks, somewhat rhetorically. Her answer:

Distrust. It is white, therefore suspect. In spite of the fact that liberating movements in the black world have been catalysts for white feminism, too many movements and organizations have made deliberate overtures to enroll blacks and have ended up by rolling them. They don’t want to be used again to help somebody gain power—a power that is carefully kept out of their hands. They look at white women and see them as the enemy—for they know that racism is not confined to white men.

Morrison’s words could easily be applied to the social movements of today. Five months ago, anger surrounding the election of Donald Trump spurred the organization of the Women’s March, a global protest whose crowd size estimates totaled more than 4 million. January 21st proved to be a largely inspiring day with men, women, and children marching in cities across the world, sending the message that sexism and a blatant disregard for human decency would not be tolerated from the leader of the United States. However, undergirding the excitement and potential for real movement building was one troublesome fact: 53 percent of white women voted for Donald Trump while 94 percent of black women voted for Hillary Clinton.

As Jenna Wortham wrote in The New York Times Magazine: “While black women show up for white women to advance causes that benefit entire movements, the reciprocity is rarely shown.” Some interpreted this type of critique as an attempt to sow unnecessary discord in an otherwise peaceful and successful movement. But it was not and still is not. It was a critique rooted in a history of white women either genuinely not understanding or, more cynically, choosing not to understand their role in maintaining the racist infrastructure of the United States. The Women’s March was applauded for being largely peaceful, without much consideration for the fact that the perceived innocence of white women shielded it from ever truly becoming violent. Linked closely with privilege, nonviolence is a luxury not bestowed on protesters in the Black Lives Matter movement or at Standing Rock.

As you move through the exhibition’s rooms it becomes increasingly clear how far we are from Ringgold’s feminist utopia. We Wanted a Revolution is divided into eight parts and organized chronologically around sets of movements, collectives, and communities between 1965 and 1985. The works from this period are threaded together by themes of solitude and invisibility associated with black womanhood.

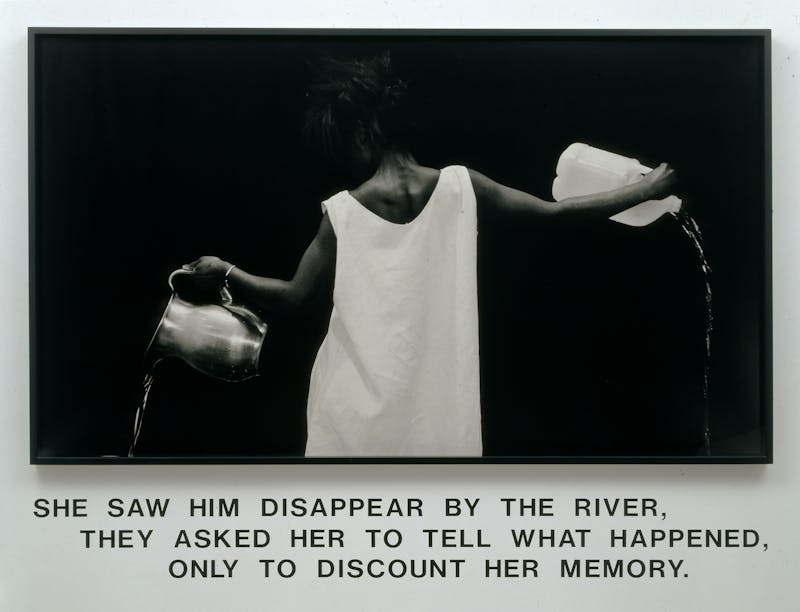

Blondell Cumming’s Chicken Soup is a harrowing performance, in which the artist mimics everyday experiences like cooking, cleaning, and folding laundry only to interrupt them with unacknowledged jagged and convulsive motions. Declared a masterpiece by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2006, Chicken Soup’s roots are found in Cumming’s observations of her grandmother doing household chores. There is Lorna Simpson’s Waterbearer, displayed on a wall of its own. Its isolation intensifies the text at the bottom, which reads: “She saw him disappear by the river, they asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” The lone black woman, whose white dress sharpens against the so black it’s almost blue background, whose posture is at once rigid and apathetic, reflects the history of erasure surrounding black female narratives. That these narratives continue to fall through the cracks has sparked a hashtag campaign, challenging us to “Say Her Name.”

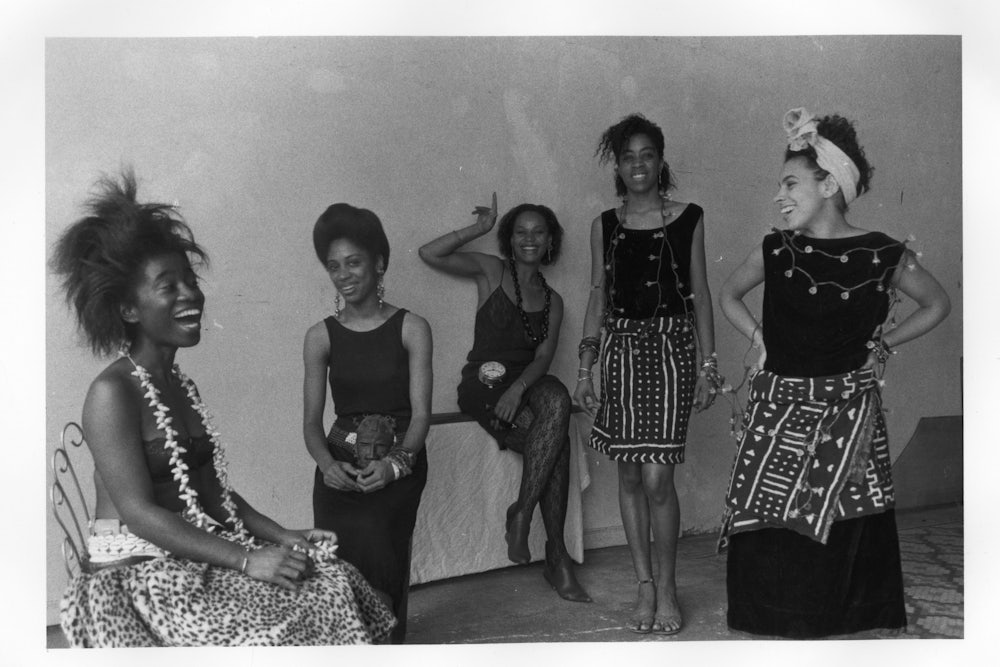

Punctuating these kinds of works are intimate artifacts—photos, letters, and notes—that reveal the support systems black women created for themselves. A letter from Linda Goode Bryant to Betye Saar asks the artist to be a part of Bryant’s forthcoming project Just Above Midtown, the first gallery space to exhibit the work of black artists in an institutional setting. There are striking and intimate photos taken by Lorna Simpson of other black female artists like Carrie Mae Weems and actress Alva Rogers. What emerges from these artifacts is the story of women forced to work in unconventional ways to ensure their voices would be heard, who forged strong bonds to remain sane, and who created community when none could be found. Thirty years later, art from black women like Solange and Beyoncé to Jamila Woods draw inspiration from these early women and their works. Lemonade, Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed visual album, sources heavily from and is an obvious tribute to Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust. The activism of artists like Faith Ringgold, for example, pushed institutional structures like the Whitney Biennial to include women and people of color.

At the Brooklyn Museum, I lingered in the exhibition space dedicated to Lorna Simpson’s Waterbearer and Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Goes to the New Museum. A desire to see Simpson’s piece, a favorite of mine, once more kept me from leaving immediately. As I moved around the floor, a woman posing next to O’Grady’s costume caught my eye. A tall blonde woman, iPhone poised, stood in front of her snapping pictures. It took a moment before I realized that this older woman, with her short dark brown hair, black ensemble, and deep red lips was Lorraine O’Grady.

It was jarring to see O’Grady sit serenely in a space she would have invaded at the peak of her career. I wanted to extract meaning from this moment because her presence measured a kind of progress. But I felt instead something between excitement and an indistinct disappointment. I looked around me; other patrons seemed unfazed by the presence of the artist. While O’Grady had successfully carved out a space for herself (and many others) within an existing system, I remembered how Ringgold imagined her women’s utopia. Her final image was inspired by listening to the women at Riker’s, hearing them talk about their desires. I wondered what would happen if black women were not just seen, but also, finally heard.