I do not know how to mend a ripped seam, patch a leak in a roof, or replace a burst pipe. I have never hung a door, taken down a door, framed out a wall, or torn down a wall. I do not know what it’s like to sleep more than one night in a row without heat. I do not really know how plumbing works, just that it is good and everyone should have it. If presented with wiring that was faulty or a floor that needed repair, I would stare at it, call the appropriate authority, or, depending on my mood, panic. I have never shit in a garbage bag.

For the squatters and housing activists and “urban homesteaders” who populate Alexander Vasudevan’s new book, The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting, this kind of handiness and resourcefulness—and the connection to space that comes with them—are not options, but necessities. The popular image of a contemporary squatter is that of a white person with dreadlocks, but Vasudevan’s sweeping research on the surprisingly radical history of occupying abandoned buildings and living in them illustrates that the stereotype is hollow.

Charting the squatting movement in several cities in Western Europe and North America, The Autonomous City begins with a violent eviction. On March 1, 2007, Copenhagen police ambushed the Ungdomshuset (“Youth House”), a social center that served as the backbone of the city’s squatting movement. After years of sitting empty, the building had been donated to a group of militant young squatters in 1982, and at the time of the eviction it housed a bookshop, café, printing press, recording studio, weekly vegan soup kitchens, and regular activist meetings; in a past life, it had been known as the Folkets Hus (“People’s House”), the fourth headquarters of the Danish labor movement and the birthplace of International Women’s Day in 1910. But when it was evacuated in 2007, it had been the property of an evangelical Christian organization for seven years, the subject of several legal battles, and a longtime source of ire for right-wing politicians, who knew it as the “pile of rotten stones at Jagtvej 69.”

The initial eviction lasted about an hour. Police surrounded the property; deployed an airport crash tender; sprayed the building’s doors and windows with a special hardening foam to prevent opening from the inside; dropped an “elite anti-terrorist unit” onto the roof from a military helicopter; and fed more officers into the upper stories from containers hoisted by boom cranes. Protests erupted at once and spread across the city over several days; as Vasudevan writes, it was “the worst rioting that Copenhagen had seen since the Second World War.” Police “accidentally” used lethal tear gas canisters against protesters and raided a series of other alternative spaces over the course of six days. By the time it was over, the demolition of the Ungdomshuset had been streamed live on a Danish television website and local prisons had run out of space from housing so many detainees. Ten years later, the former Ungdomshuset site remains an empty lot.

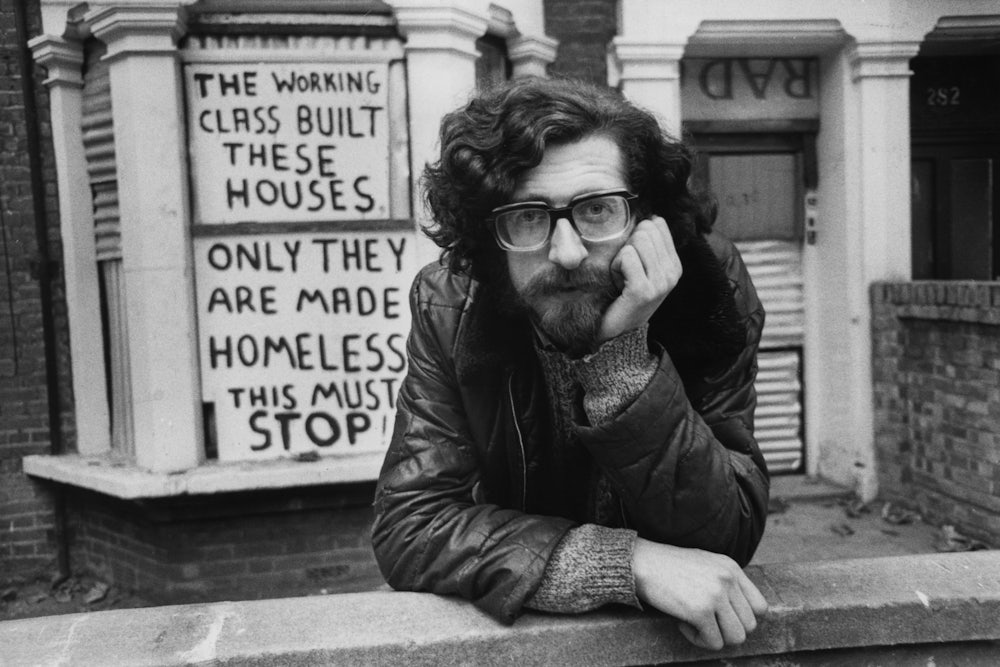

Governments have never liked squatters, but such fierce antagonism between the squatter and the city is a relatively recent development. Many people supported squatters in the middle of the twentieth century; in 1946, the Daily Mail praised the nearly 40,000 squatters who were organized by the Communist Party and Women’s Voluntary Service and scattered throughout England and Wales following World War II: “The ‘invasion’ of empty service camps is a refreshing example of what ordinary people can do when they have a mind to do it … a warning that people will not put up forever with empty promises.” Vasudevan tells of one occupation in which police officers helped squatters carry their suitcases inside. After all, the logic of squatting makes a lot of sense—people need a place to live, and these buildings are empty.

Vasudevan makes connections to rent strikes and actions dating back to the 19th century, even suggesting, in his chapter on Vancouver, that settlers who displaced indigenous communities were enacting a kind of colonial squatting, though at the time the frontiersmen lobbed the term at indigenous families who refused to leave their homes. But squatting as we know it—the occupation of empty or abandoned properties by low-income or politically motivated people—didn’t really ramp up until the late 1960s and early ’70s. From New York to West Berlin, London to Turin, the struggle for decent, affordable housing intersected frequently with other international movements for social change, including the student movement, Black Power, women’s liberation, and gay liberation, and it resulted in thousands of people all over the world declaring, in the worlds of Henri Lefebvre, their “right to the city.”

Although squatting fundamentally arose out of housing precarity, it inevitably engulfed much more than that. Soon, groups like Operation Move-In in New York City had developed a repertoire of tactics to place low-income families in homes, and the process required recalibrating one’s relationship to the place one lived. Squatted buildings were usually dilapidated and severely in need of repairs, which, in the absence of landlords, had to be performed by the squatters themselves. In 1981, a West Berlin squatter noted that “on such premises, there is always something that is not working … you develop a kind of relation to it which you could call responsibility. You know where the cables run, as much as you know the sounds of the environment, the people, it is all interconnected.” A Puerto Rican woman whose family had lived with relatives for seven years before being placed in an apartment by Operation Move-In said, “I knew it was illegal, but I felt something right would come out of it.”

That sense of rightness, Vasudevan argues, is part of the “collective world-making” that still takes place inside squats today. Zines and publications about how to resuscitate dwellings circulate; occupants share food and other resources; and despite the inherent tenuousness of the squatters’ position, a sense of autonomous purpose and “creative destruction” propels more organizing. They must maintain an aggressively short-term perspective—they could be evicted any day—as well as a utopian vision of a liberated future.

Nevertheless, this more ideological bent has long created tensions within squats that compound the constant threats from the outside. As the movement expanded in the ’70s and ’80s, in the minds of some it split into “deserving” squatters, who had nowhere else to go, and “undeserving” squatters, who were in it for political reasons (and might have, it was suspected, had other resources available to them). There were those willing to cooperate with the city to eventually obtain legal ownership of their buildings, and those who considered any deal with the man a failure of the project. Vasudevan told me that “whether it was who was cooking for everyone this evening or who was doing the cleaning, all kinds of really everyday, banal things became very politicized” in squatted spaces. But the broader issues that beset the squatting movement concerned whether to endeavor to utilize the forces of the state, or attempt to escape them.

Though squats still exist, the last two decades have seen cities drift toward criminalization, with evictions on the rise. Vasudevan often refers to the need to document the history of squatting before it’s too late. (The Autonomous City is billed as “the first popular history of squatting in Europe and North America.”) While crackdowns have always taken place, the possibility of squatting as a means to usher in a better world seems to have dimmed. By the middle of the ’80s, the anarchist historian x-Chris wrote that “the Left had dumped squatting as both a political project and as a practical solution to aspects of the housing crisis.”

In the context of the current global housing crisis, Vasudevan says, it is “not hard to see the new wave of anti-squatting legislation as an attempt to protect the ongoing commodification of housing at a moment when many people are looking to alternatives that reassert the cultural, social, and political value of housing as a universal necessity and as a source of social transformation.” The conditions described in Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City are not dissimilar to those Vasudevan invokes as the inspiration for squatters in the mid-20th century: craven landlords who refuse to make repairs; exploitation; families who are forced to stay with friends or relatives and bounce from unlivable apartment to unlivable apartment because they can’t afford rent. Some writers have even called to “bring back squatting.”

On the flip side, many of the squats that survive have been too successful for their own good. Vasudevan is not as descriptive as the middle-class voyeur would like; instead of taking the reader inside an abandoned building, he reiterates that the politics of going there are radical. While this makes for an academic reading experience, it might also be the most responsible way for an outsider—Vasudevan told me that he has never squatted himself—to approach the practice. In places like Berlin, he writes, the attractively punky squat ethos has “played a decisive role in Berlin’s ongoing neo-liberal restructuring.” Abandoned buildings and “pop-up” spaces—once undesirable signs of decay and economic precarity—are now the powerful marketing tools of a laid-back yet adventurous city. In one 2009 Guardian article, a delighted expat dipped a toe in the Berlin squat scene by having dinner and going to a concert at a couple of “living projects” in the former East; her piece ends with a list of squats written in the style of a travel guide, with contact numbers and websites and a recommendation for which squat serves “great stone-baked pizza.” Three years later, the most famous “art squat” on the list, the massive Tacheles in Mitte, was evicted. Two years after that it was sold to developers, its prime location “one of the last undeveloped stretches of Berlin’s popular Mitte district, which the developers cited as a prime reason for their investment.”

Speaking to the Guardian in 2015, the photographer Ash Thayer, who lived in and documented one of the few remaining squats in New York, C-Squat, from 1993 until 2000, highlighted the sense of loss she felt about the success of her home, which the squatters were able to convert into a co-op through a deal with the city. “It was incredibly hard and unglamorous,” she says of her time living there. “In the winter there were blizzards. Getting up in the middle of a night, freezing, to pee in a bucket was not desirable or fun.”

But, she added, “We were really living out our ideals. There’s a sense of victory, but also a little bit of sadness, because I wish I could have this community again.”