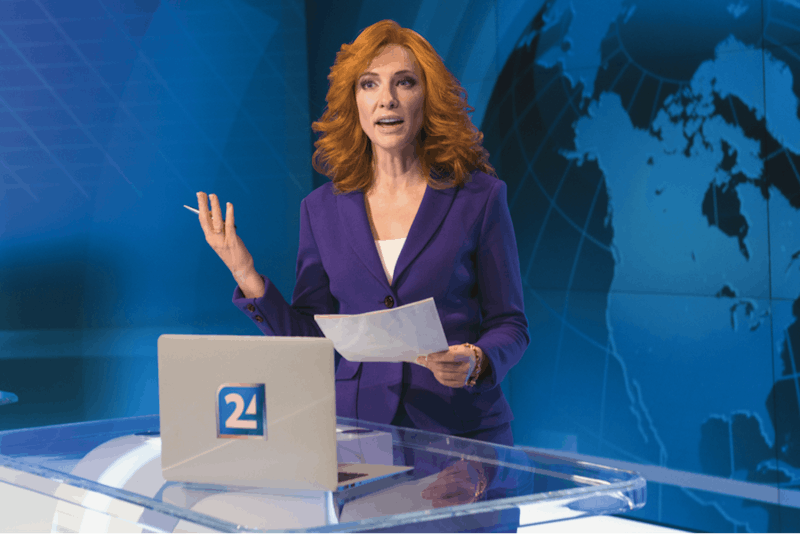

“Good evening ladies and gentlemen, all art is fake.” Orange bouffant rustling, the newscaster speaks in the melody of her kind: “Maybe the mini-artist is a very small person.” Those words are Sol Lewitt’s—from “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”—but the voice and enunciation and staging are CNN. The newscaster, played by Cate Blanchett, does a classic smize and holds her head very still while listening to a correspondent who is out in the rain, also played by Cate Blanchett. The newscaster is just one of Blanchett’s 13 different roles in Manifesto. Others include a roaring homeless man, a puppeteer, and a harried mom who works in a garbage disposal plant. Each character recites from an artist’s statement in a tenor that matches the scene’s chosen delivery mechanism: eulogy, prayer, factory loudspeaker.

The film adapts German artist Julian Rosefeldt’s screen installation work of last year, which lived at the Park Avenue Armory in New York. Blanchett’s fans have seen her take on experimental roles before. In Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee and Cigarettes, she played herself and her own fictional cousin Shelly. In I’m Not There, the Bob Dylan multiverse vignette-athon, she played an avatar of Dylan in the 1965-66 era of disillusionment and electrification. Blanchett occupied that male role with languor and sex appeal. She has a couple of Oscars now (The Aviator, Blue Jasmine), which, along with her persistent beauty, bolster her haute-art credentials with old-fashioned bankability.

The movie was shot over 11 days, which is insane considering that Blanchett acts in 12 different accents. “For instance,” Rosefeldt says in a director’s statement, “we had to do half of the scene with the homeless man on the same day as the newsreader.” The accents are not perfect at every moment; the Yorkshire mum’s voice wobbles a bit, and the homeless man is sometimes Scottish and sometimes Irish. But the production is extraordinary considering the constraints.

Music by the German electro-classical composer Nils Frahm and Ben Lukas Boysen hums over long, elegant shots that dwell as much on the movie’s environments as on its star. Cinematographer Christoph Krauss gives us the concrete ruins of modernist innovation in architecture; a recursive, Escher-like stock market floor; a funeral procession in a cold wood. The puppeteer scene features the work of puppet-master Suse Wächter, who has produced a tiny version of Cate Blanchett that exactly has her smile.

A lot of the movie is funny, because it is absurd. The funeral speaker/Dada scene is especially good. We open on children playing in a wood. They run to join a funeral procession, which is mournfully led by reed and brass instruments. The grieving woman steps up to a lectern at the graveside. She could be the widow. She looks rich. Her voice catches and she begins to cry as she bellows that she wants to shit in different colors, speaking the words of Tristan Tzara in his Manifesto of Monsieur Aa the Antiphilosopher (1920).

Julian Rosefeldt met Blanchett through a mutual friend, and their collaboration sprang up quickly. Rosefeldt had stumbled over “two manifestos by the French Futurist poet and choreographer Valentine de Saint-Point and was immediately set on fire.” In his director’s statement, he writes that he “read the artist’s manifesto firstly as an expression of defiant youth, then as literature, then as poetry—so to say, Sturm und Drang remastered.”

Art as remastering is an interesting proposition, especially in its technological language. It also prompts the question whether a gallery installation—Manifesto originally consisted of multiple screens hanging from a ceiling—can be “remastered” into a feature film without compromising the original. Indeed, Manifesto contains an extreme multiplicity of medium, since it draws upon text, film, performance, costuming, fine art. It also treats art history as a medium itself, even as a kind of political history. After all, so many manifestos are written in the face of an enemy.

Art manifestos have always been notable for their “utopian energy,” as Rosefeldt notes. In his director’s statement, however, Rosefeldt makes the odd claim that his work is an intervention:

…in a time where neo-nationalist, racist and populist tendencies in politics and media threaten again democracies all over the world and challenge us to defend our allegedly achieved values of tolerance and respect, Manifesto becomes a clarion call for action.

In fact, Manifesto presents 13 contradictory treatises, performed by a broker, a mother, a manager, a woman at a funeral, an eyelinered punk, a choreographer, a teacher, a factory worker, a newsreader, a reporter, a puppeteer, a scientist, and a homeless man. They do not form a coherent bloc, nor does the film seem to evangelize for any position in particular, apart from a general approval of vehemence.

In an early scene a broker reads from an array of Futurist manifestos by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Guillaume Appollinaire, Dziga Vertov, and more. The Futurists’ condemnation of history-fetishizing museums is compelling, but they also presented a violent vision of progress that various fascist movements have read with approval. “We will glorify war,” they say, “the world’s only hygiene.” They long for violence, destruction, the valorization only of perfect youth, and “scorn for woman.”

The Futurists were in some respects simply nasty, and it is difficult to see how Rosefeldt sees their texts as part of his “clarion call.” Rosefeldt does not endorse these manifestos: Each scene is so powerfully colored by the ritual in which the script plays out that the viewer cannot really connect to the words as they were meant to be heard. Instead, a principle of disjuncture emerges. On a simplistic level, the mismatch between Situationist writings and the dragging limp of the homeless man reveals our expectations of both, and is funny because it plays with those expectations. It’s the same with the Southern mother who reads Claes Oldenburg’s “I am for an Art…” (1961) while her family bows their heads over the lunch table.

The film needs no coherent platform in order to explore its subject. So why does Rosefeldt frame it as an intervention? Perhaps he is advocating for a return to energetic, politicized conversations in contemporary art; for a dialogue between contemporary art and politics per se. Manifesto also valorizes multiplicity and simultaneity as an organizing principle, suggesting that even the most self-serious manifesto only truly belongs alongside other self-serious manifestos. None of them have the answer: only questions, only selves.

The theatrical premiere of Manifesto is Wednesday, May 10, at Film Forum in New York.