The legend of F. Scott Fitzgerald has flourished for so long that we forget how much of it was the creation of Fitzgerald himself, with help from some of the highest cultural priests of midcentury America. Foremost among them was Edmund Wilson, a friend since their Princeton years, who shepherded Fitzgerald’s final, uncompleted novel, The Last Tycoon, into publication in 1941, and then assembled the pieces of The Crack-Up, which included the classic title essay on Fitzgerald’s nervous breakdown in the mid-’30s. Its reviewers included another eminence, a plainly infatuated Lionel Trilling, who compared early Fitzgerald to the author of The Sorrows of Young Werther, “both the young men so handsome, both winning immediate and notorious success, both rather more interested in life than in art, each the spokesman and symbol of his own restless generation.”

Wilson admired Fitzgerald, and worked to revive his reputation, which had sunk low at his death in 1940. But even he was startled to see Fitzgerald, in all his liveliness, humor, and wit, as well as his ruinous alcoholism, resurrected within a few years as “a martyr, a sacrificial victim, a semi-divine personage.” As early as 1951, Fitzgerald had assumed “a national or American significance as well as a literary one,” wrote Delmore Schwartz, himself an expert in the wages of misspent talent. “He can be regarded as a toy, puppet, and victim of the zeitgeist [and] will certainly be invoked as a witness of how America destroys its men of genius by giving them a false and impossible idea of success.” Neither Wilson nor Schwartz foresaw—but then who could have?—how far it would all go: the Scott-and-Zelda Amazon serial Z: The Beginning of Everything, with a miscast Christina Ricci clad in a Gorgon’s-head merkin; or the “Great Gatsby Package”—$14,999 for three nights in a hotel suite ornamented with a magnum of Champagne and a “personal note” from the hotelier’s daughter—yes, Ivanka Trump.

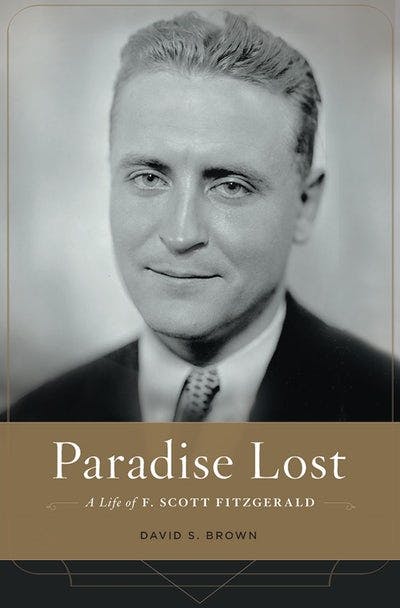

David S. Brown, in his biography Paradise Lost, is the latest Fitzgerald admirer to seek a larger national significance in his myth. Brown’s field is American history, not literature (he is the author of the intelligent Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography), and in his view Fitzgerald was a historian, too. The laureate of the Jazz Age was also, he proposes, a prophet of economic and political transformation. Even as Fitzgerald partied with snobs in Princeton eating clubs and got smashed with plutocrats in swanky Manhattan hotels, he stood apart, Brown tells us, and should be seen “ideologically as a man of an older, precapitalist Right.” This put him in august intellectual company. Like the declinists Henry Adams and Oswald Spengler, Fitzgerald “doubted whether older pre-Enlightenment notions of art, creativity, paternalism, and worship would survive the onset of what we have since come to call ‘modernity.’ ” With Frederick Jackson Turner, he explored “the meaning of a frontierless America”; with Charles Beard and Thorstein Veblen, he “interpreted” the excesses of the boom years; and with John Maynard Keynes, he intuited the collapse of the global economic order.

But these mighty guns, once wheeled out, fall more or less silent, and that’s a good thing, because when Brown does deploy them we get misfires like this: “Only the fact that Fitzgerald almost certainly never read Veblen prohibits us from seeing the novel”—The Great Gatsby—“as a parody of Veblen’s ideas.” Or: “Beard, of course, was a trained historian who visited archives, sampled secondary materials, and appealed to his profession by putting forth hypotheses backed by evidence and footnotes. Fitzgerald in his own way did much the same. His archives were any number of bars, newspapers, beaches, and cities.” It begins to feel not so much wrong as beside the point.

In truth, while Fitzgerald read a bit in the major theorists of his time, including the fashionable prophets of doom, he was “extraordinarily little occupied with the general affairs of the world,” as Wilson reported in 1922. His thinking went chiefly into his craft; he prided himself on being “a worker in the arts.” Brown’s depiction of Fitzgerald as stern defender of a vanished age and grim diagnostician of “a larger cultural illness corrupting the West” encumbers a writer whose power of enchantment begins in swift movement and lightning observation, irradiated by delicious humor and also the dreamy moonglow of his charming, musical prose.

And yet Brown is right in one important way. Fitzgerald really did create a kind of history. He did this out of his uncanny feel for the excitement of his moment and of how fleeting it was. Being “the historian of his generation and for a long time its most famous symbol” made him “in some ways inherently more interesting than any other [writer] in his generation,” Alfred Kazin argued in On Native Grounds. Fitzgerald himself recognized that he was as much the “typical product” as “spokesman” of his time, lit by the same competitive fevers as so many others: He wanted to make money, be a “big man,” and get “the top girl”—only he elevated those banal ambitions into romance. Better than anyone else, he grasped that America in the post–World War I boom “was going on the greatest, gaudiest spree in history,” as he wrote with a gold prospector’s confidence, “and there was going to be plenty to tell about it.”

It is this thrill of news that gives Fitzgerald’s work its special hush even as it discloses, or seems to, the secret meaning of his time. It hit with the force and authority it did because, as Brown rightly says, Fitzgerald was a Midwestern moralist, even a prude, with “ultra-conventional views on sex, marriage, and child rearing.” The war between appetite and judgment was a source of tension in his work, as it so often has been for American writers who combine social striving with literary ambition. The moral judgment comes, but it is the tender, rueful judgment of the morning after, with the strong cold light pouring in and the empty bottle on the nightstand.

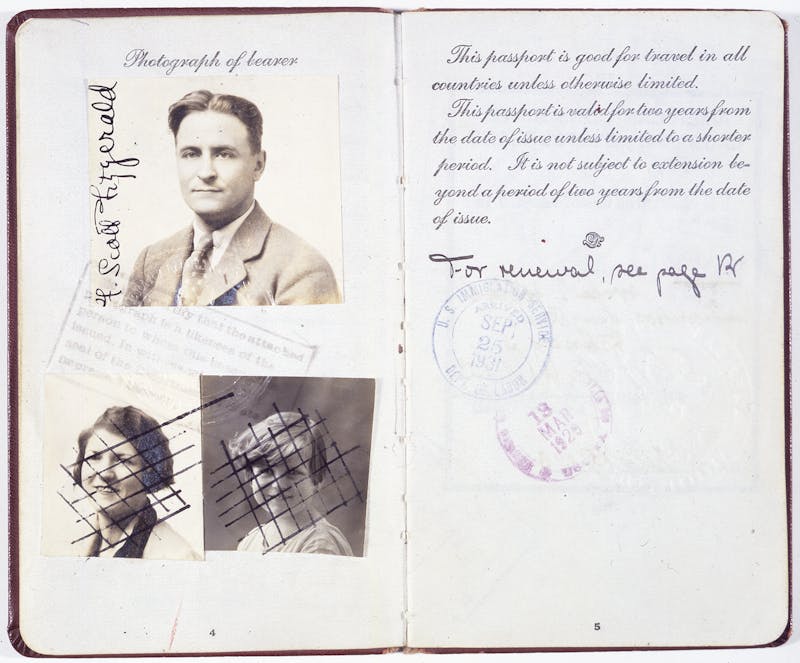

Brown’s biography is best when he simply tells the story, which he does well once he gets going. With a surer sense than more gossipy writers, he fits Fitzgerald’s life into the broader American history of his time and also into its geography. Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, and educated in the East—at a Catholic boarding school in New Jersey, and then Princeton—Fitzgerald spent time in the Deep South (Montgomery, Alabama, where he met and wooed Zelda Sayre) and the Border South (Baltimore, where they lived for a time in the 1930s). Add to these his spendthrift years in Manhattan, the long expatriate sojourn in Paris and on the French Riviera, and his bleak final days in Hollywood, and the result is a privileged life but also an expansive one.

The surprise with Fitzgerald, who died at the age of 44, is how quickly he matured. The same author who drew a repugnant picture of immigrants (“aliens” with their “exceptionally ugly faces” and their “smells”) in The Beautiful and Damned soon captured, with brilliant precision, the Nordic-race drivel of the upper classes in Gatsby (“it’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved”) and still later invented a plausible Jewish mogul modeled on Irving Thalberg.

Like most romantics, Fitzgerald was as much a boat going with the current as against it, and he was borne as much into the future as the past. Even his callow early work is true to the mood of change. It is filled with the cosmopolitan busy-ness of crowded cities and skyscrapers—no one ever wrote better of Manhattan’s glamour and its loneliness (see “My Lost City”)—and the excitements of jazz and film, to which he responded with the exuberance of a very young writer growing up in public. In the 1920s, when he was both heartthrob and literary man, Fitzgerald fascinated his fellow writers as much as he did his fans, with his well-cut clothes and chiseled Silent Screen profile; his drunken antics in expensive hotel suites; plus the rich-folk trappings of valet, butler, chauffeur, governess, and even a secondhand Rolls-Royce. He made no excuses for the rich, but he didn’t sanitize his own actions either. He chose the novel over, say, musical comedy, because, as he told his daughter, he wanted “to preach at people in some acceptable form.” His excess was bound with guilt and shame, as it is for all good American puritans.

Hemingway’s pages on Fitzgerald in A Moveable Feast, for all their cruelty, capture the true source of Fitzgerald’s appeal as both person and writer—in his guileless compulsion for intimate, at times embarrassing, disclosure. As soon as they met, Fitzgerald interrogated Hemingway on his marital sex life and before long poured forth the history of his troubles with Zelda. The same candor deepens his writing, too, and makes him seem less a romantic fabulist than a spiller of dark, thrilling secrets—his own, in essays like “Early Success” and “The Crack-Up”—but also other people’s. “He was always on the outside looking in,” said his first major crush, the debutante Ginevra King. This could describe a wide-eyed social climber or poor relation on the make. But it could also describe a Peeping Tom, furtively peering into hidden worlds. Fitzgerald was both.

The innovation in Gatsby comes, of course, in Fitzgerald’s narrator, Nick Carraway—an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Marlow, who establishes a triangulating distance between the reader and the story. This allows Fitzgerald to withhold simple facts of Gatsby’s biography and of his criminal activities, and so drape him in mystery, giving “largeness to what might be small if it were known,” as John Updike once wrote. It also correlates with Fitzgerald’s theme. Gatsby’s mysterious empire of bootlegging “drugstores” quivers with the same mirage-like falseness as the paper fortunes built on credit in the boom years, and like them is primed for collapse.

Narratively it all works, and satisfies us as readers, because Fitzgerald’s withholdings are offset by a larger drama of illicitness, each disclosure (Jordan Baker’s golf cheating, Gatsby’s shadowy partnership with Meyer Wolfsheim, Tom Buchanan’s mistress) unfolding in an atmosphere of sneaked glances and peekings-in, of continual eavesdropping, conversations not heard but overheard. Carraway, the Midwestern visitor renting a small cottage next door to Gatsby’s colossal “factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy,” is like his author—like us—the outsider looking in.

The hidden story of Gatsby is sex—as crime, as dangerous lure, as destructive habit. And the criminals are women, because they hold the power to seduce. Fitzgerald found this theme early, in the scandalous passages on “petting” in his first novel. The phenomenon had been written about, with alarm, since 1915. What was new in Fitzgerald’s treatment was that the aggressors often were young women, chaste huntresses making conquests one after another. This was the liberating break with Victorianism: the corset ripped away to reveal a deeper self-possession. He merged this discovery with the theme of sexual transaction pioneered by Edith Wharton and Theodore Dreiser, older novelists he admired and met. Wharton’s imprint, especially, is stamped on the early story “The Rich Boy,” with its card-playing idle rich gathered at their vacation spots; and Bloeckman, the Jewish movie producer in The Beautiful and Damned, is a descendant of the predatory Rosedale in Wharton’s The House of Mirth.

Fitzgerald’s women remain economically imprisoned, but enjoy the sexual advantage. The action in Gatsby is driven by its femmes fatales, each a variation on the kept woman: the upper-class Louisville belle, Daisy, languishing in her gilded cage; the tomboy athlete, Jordan Baker, who sponges off wealthy friends as she travels from one golf tournament to the next; the adulterous housewife, Myrtle Wilson. For Gatsby, Daisy is the “top girl,” and her allure feels monetary. “It excited him, too, that many men had already loved Daisy— it increased her value in his eyes.” We almost hear the whir of the adding machine, and finally we do, when Gatsby blurts, “her voice is full of money.” With that she morphs from person to price tag.

Fitzgerald is less the heir of Veblen, perhaps, than of Marx, who described the fetishizing of commodities, manufactured objects created by human labor yet somehow “abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” Marx was being satirical, but so is Fitzgerald when Gatsby gives Daisy a tour of his mansion and begins pulling his tailored clothing from “two hulking patent cabinets which held his massed suits and dressing-gowns and ties, and his shirts, piled like bricks in stacks a dozen high.” Daisy is overwhelmed with emotion. “‘They’re such beautiful shirts,’ she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. ‘It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.’ ”

Fitzgerald’s New York “owed little to Wharton’s aristocratic acre of ducal families,” Brown observes. “He focused instead on the new money, the fresh sources of cultural power.” True enough, but he also saw that in America even patricians will affect the demeanor of the self-made. The fortune must seem earned anew by each generation, the purity of the initial conquest kept fresh. This, in turn, breeds an almost fanatical materialism. The glamorous Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, too, coveted the talismans and tokens of success. “I don’t mean that money means happiness, necessarily,” Zelda said in an interview in 1923. “But having things, just things, objects makes a woman happy. The right kind of perfume, the smart pair of shoes.” Her husband, hovering near, piped in to clarify, “Women care for ‘things,’ clothes, furniture, for themselves … and men, in so far as they contribute to their vanity.” What Fitzgerald once described as his peasant’s “smoldering hatred” of the rich began in his knowledge, gained from the shabby gentility of his youth, that status was measured in dollars.

And yet Fitzgerald, for all his knowingness, seems oddly childlike. Critics from Trilling to James Mellow—in Invented Lives, his stylish portrait of the Fitzgeralds’ marriage—have noted the old-fashioned chivalry, or reticence, in Fitzgerald’s discussion of sex. Born in the last gasp of the Victorian age, he cherished its standard of feminine purity and its worship of pristine childhood. His ideal heroine—in life and in art—was the “wise, even hard-boiled, virgin who for all her daring and unconventionality was essentially far more elusive than her mother,” Arthur Mizener wrote in The Far Side of Paradise, the first Fitzgerald biography and still the best. Ginevra King was all of 16 when Fitzgerald met her on a Christmas break from Princeton. Zelda, when he met her, had just turned 18, “so young that she had not put up her hair and wore the frilly sort of dress that used to be reserved for young girls,” Mizener writes.

Nymphets flit through Fitzgerald’s fiction. The heartbreaker in the early story “Winter Dreams” seems in almost total possession of her sexual self at age eleven. “There was a general ungodliness in the way her lips twisted down at the corners when she smiled, and in the—Heaven help us!—in the almost passionate quality in her eyes. Vitality is born early in such women.” Even as Fitzgerald grew older his heroines remain children. The 17-year-old starlet Rosemary in Tender Is the Night, whose “body hovered delicately on the last edge of childhood,” was based on the actress Lois Moran, also 17 when Fitzgerald met her. (“You … engaged in flagrantly sentimental relations with a child,” Zelda later accused him.) The 19-year-old Cecilia Brady in The Last Tycoon, written when Fitzgerald was in his early forties, pines for the mogul Monroe Stahr yet also wishes time could be turned back to when “I would have been nine.” This yearning, we feel, is Fitzgerald’s own. He, too, would like to recover his virginity. Zelda was the first and up to that time the only woman he had ever slept with, he told Hemingway in the mid-’20s. There is little reason to doubt so unusual a boast.

It’s not surprising that Fitzgerald’s heroes included T.S. Eliot—the poet of impotence in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and of sterility in The Waste Land—and that Eliot should have called Gatsby the “first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.” Fitzgerald would never advance beyond it—but neither would anyone else. Gatsby remains the classic every American knows, just as everyone once knew Huckleberry Finn. Both can be read either as pastoral hymns for a lost America or as unsparing critiques of a false innocence. The famous last page in Gatsby, the lament for the denuded virgin land—“Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams”—turns on the image of procurement. Carraway’s role in the drama is literally that of the go-between Pandarus, who arranges the star-crossed lovers’ trysts. Sexual transaction has become a metaphor for the marketplace of the American dream.

“My whole theory of writing I can sum up in one sentence,” Fitzgerald once explained. “An author ought to write for the youth of his own generation, the critics of the next, and the schoolmasters of ever afterward.” At the time he was 23. This Side of Paradise was already in its third printing, two months after its publication in March 1920. Things would never be so good again. “The compensation of a very early success is a conviction that life is a romantic matter,” he later wrote. “In the best sense one stays young. When the primary objects of love and money could be taken for granted and a shaky eminence had lost its fascination, I had fair years to waste, years that I can’t honestly regret, in seeking the eternal Carnival by the Sea.”

The carnival was the Cap d’Antibes, where the glorious opening pages of Tender Is the Night are set. The novel, published in 1934—nine years after Gatsby—was a struggle to complete and is riddled with missteps, but it remains a classic, more readable than almost any other American novel of the 1930s. The story of Fitzgerald as a wastrel and a victim of his own indiscipline is attractive but exaggerated. He worked steadily, diligently, almost continually. In 21 years as a professional writer, he completed four novels, was midway through a fifth, finished a full-length play, and brought out four closely pruned short story collections, as well as essays like “The Crack-Up,” which helped invent the modern confessional memoir. And he left behind so much other writing that at this late date some is coming to light for the first time—including the 18 “lost” stories, almost all of them written in the 1930s, in the new collection, I’d Die for You.

Even Fitzgerald’s final days in Hollywood were more productive than we may suppose. He went there for a most pragmatic reason, to get his finances in order—Zelda was now institutionalized, their daughter was at Vassar—and he succeeded. In his 18 months at MGM, “Fitzgerald earned nearly $90,000—about $1.4 million in contemporary dollars,” Brown reports. Once you add “freelance work at 20th Century-Fox, Columbia Studios, Goldwyn, and Paramount Universal, the figure jumps to some $125,000, or about $2 million in current earnings.” He also began a relationship with a prominent Hollywood journalist, Sheilah Graham, who kept him on course with his work and to whom he seems to have been devoted (even if he scrawled “portrait of a prostitute” on the back of the framed photo he kept of her). He was a flop at writing for the movies, but he learned a great deal about them. The script-writing and -editing scenes in The Last Tycoon, one of the handful of really good Hollywood novels, vividly describe the techniques and mechanics of filmmaking and show its power as a narrative medium.

Wilson was justified in saying, in his foreword to the published draft, that it promised to be Fitzgerald’s “most mature” novel. The conjuror of “The Ice Palace” and “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz” and the “rose-colored hotel” rising up from the Mediterranean haze found in the “dream factory” of the great Hollywood studios his most congenial subject. “Under the moon the back lot was thirty acres of fairyland,” Fitzgerald writes, with his magician’s touch, “not because the locations really looked like African jungles and French châteaux and schooners at anchor and Broadway by night, but because they looked like the torn picture books of childhood, like fragments of stories dancing in an open fire.” The leap from private fantasy to the Ages of Man is too fluent, but that is Fitzgerald’s point, the illusion of permanence and depth beneath the shallow surfaces. The make-believe sets, like Jay Gatsby’s flimsy mansion, tremble in the gusts of an invading realism.

Fitzgerald accurately guessed that the world brought alive in The Last Tycoon was already headed for extinction in 1940. For this reason he set the action earlier, in 1935, the near-bottom of the Depression, when, as he explained to an editor, Hollywood had given the public “an escape into a lavish, romantic past that perhaps will not come again into our time.” It also gave Fitzgerald one last shimmering frame in his moving picture of the despoiled American dream, bared in all its “meretricious beauty.” In the end his delicate instrument has proved just as durable as he hoped—“as if,” like Gatsby, “he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away.”