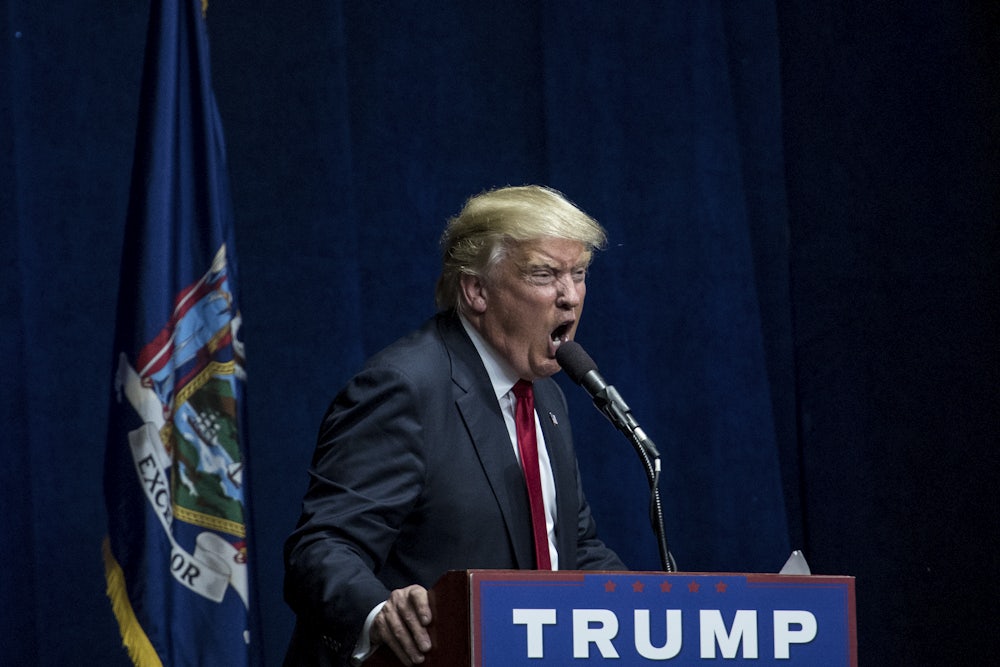

Donald Trump’s political career has been defined by his philandering relationship with the truth. When reality doesn’t meet his needs, he rejects reality until reality changes or he finds someone or something to blame for the disappointment.

If attendance at his campaign rallies sagged, he would nevertheless boast about his “record crowds.” After debates and at various other intervals he would tout fictional or outlying polls that had him winning (joke’s on us—he won). When stubborn facts still refused to accommodate him, he would retreat to the aggrieved terrain where he and his core supporters connected most strongly, scapegoating Muslims and Mexico and China and (((globalists))) for all of the world’s problems. When huge crowds failed to materialize for his inauguration, he claimed the fake media used camera tricks to obscure throngs of adoring fans.

This lizard-brained need to be the humiliator rather than the humiliated does more to shape his governing than usual presidential considerations like consistency, merit, and impact on people’s lives.

“No administration has accomplished more in the first 90 days,” Trump declared at a manufacturing event in Wisconsin earlier this week. “That includes on military on the border on trade on regulation on law enforcement—we love our law enforcement—and on government reform.”

"The first 90 days of my presidency has exposed the total failure of the last eight years of foreign policy!" So true. @foxandfriends

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 17, 2017

Like his record-shattering inauguration turnout and “massive landslide” electoral-college victory, these claims reside in the crowded safe-space of Trump’s imagination. With exceptions for his administrative action in the regulatory and immigration enforcement realms—and the Supreme Court appointment of Neil Gorsuch, a fait accompli—Trump’s first months in office have been marked by incompetence, backstabbing, judicial injunctions, and legislative failure.

Sensing a public relations disaster looming at the 100-day mark next Saturday, the White House is reportedly pressuring House Republicans to take another run at an Obamacare alternative, tweaked this time around to abolish the federal ban on discrimination against people with pre-existing conditions.

This new push would reprise the initial Republican health care strategy of writing a bill in secret and trying to rush it through the House in a few days, ahead of any official analysis of its impact on coverage or cost. At the time of this writing, there was no bill text, no agreement in principle, no whip count, and loud whispers of doubt emanating from the Hill that the effort, like the first one, is an exercise in futility.

We can hope that the whole thing falls apart again, or that a bill comes to a vote, and fails to pass, or that it passes but dies in the Senate. The risk is that under deadline-driven duress, and to prevent a self-fulfilling prophecy from taking hold, House Republicans pass something reckless and unworkable that takes on a life of its own and—against all odds—becomes law.

Fortunately, Republicans returning from recess were just reminded (by constituents at town halls and special-election voters in Kansas and Georgia) of how dangerous taking such a vote would be. Congress also needs to fund the government by the end of next week. Under the circumstances, it is farfetched to imagine them also passing a legislative garble like the GOP’s American Health Care Act that restructures one-sixth of the economy.

But the Trump problem doesn’t end with that failure. There is no such thing as a chastened Trump.

To reassert himself as the humiliator, Trump will look to take decisive action of some kind elsewhere. With the legislative channel all but closed, he will find something in the administrative and foreign policy realms over which he exerts outright control. He could sabotage Obamacare by announcing an end to cost-sharing reduction payments. He could void the nuclear deal with Iran. He could provoke North Korea. But there is no historical precedent that allows us to comfort ourselves in the hope that he will accept defeat quietly. When Trump needs a “win,” we all lose.