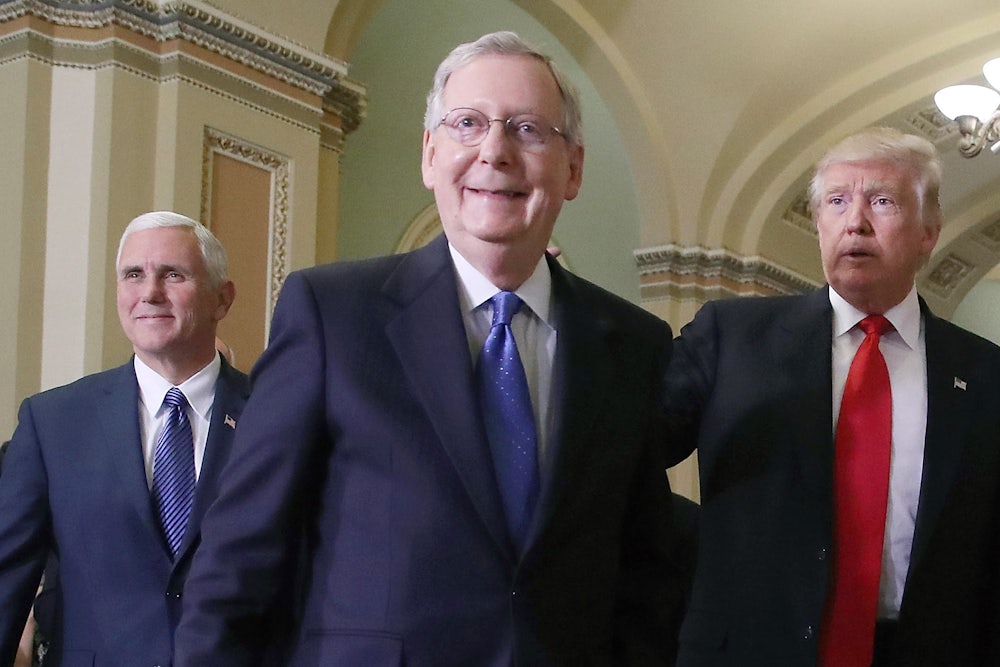

The long-awaited abolition of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees is expected to go as follows: On Thursday, Democrats will deny Judge Neil Gorsuch the 60 votes he needs to overcome their filibuster. In response, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will invoke the “nuclear option” to change Senate rules so that bare majorities can overcome Court filibusters, rendering the filibuster purely symbolic.

In the prelude and aftermath, you will likely learn (if you haven’t already) that the demise of the filibuster is a dark moment in the history of U.S. politics, the culmination of long-escalating partisan warfare over Court nominees. This is a doubly convenient fiction because it apportions blame equally between parties and suggests judicial-power politics would give way to bipartisan judicial consensus if only similarly reasonable people would prevail.

Both implied propositions are wrong, and the premise—that supermajorities should be required to confirm federal judges—is deeply contestable.

There are many convincing reasons Democrats should proceed with their filibuster Thursday, but perhaps the most satisfying is that it will bring clarity to the dynamics governing the appointment and advice-and-consent powers. The only good that came of McConnell’s ruthless and unprecedented decision to orphan Court nominee Merrick Garland last year—to nullify Obama’s appointment power by abdicating the Senate’s advice and consent responsibility—was that its shamelessness was revelatory. The GOP could no longer pretend any real principle was at stake, and the Democrats, by filibustering Gorsuch, can now kill these disingenuous conceits that have defined Supreme Court battles for too long.

Most observers, even those who lament it, now see that the abolition of the Supreme Court filibuster was inevitable. Indeed, shrewd observers note that the Court filibuster has been effectively dead for many years. It died as a consequence of factors beyond the control of individuals: the ideological polarization of partisan politics, and a constitutional structure that gives the Senate total control over who gets lifetime positions as the ultimate arbiters of law in America.

All of the incentives in this environment point toward maximizing victories and minimizing defeats; the only things restricting a much more rapid devolution of the confirmation process into pure power politics were unenforceable norms of behavior. Once those began to give way, the filibuster was doomed.

It is pleasing for reporters and opinion writers to imagine that the norms fell like alternating partisan dominoes, one act of retribution begetting another. But the truth maps much more neatly on to another hard political truth: that the polarization of our political parties has been asymmetric. Republicans have become procedurally extreme more quickly than Democrats, and their leader, McConnell, is an unapologetic violator of norms.

Conservatives always point to the failure of Robert Bork’s Supreme Court nomination 30 years ago as the original sin precipitating the breakdown of these norms. The reflex is so ingrained that they have habituated multiple generations of journalists into asserting that Democrats filibustered Bork, President Ronald Reagan’s nominee, when no such filibuster occurred. Indeed, the Senate rejected Bork outright, on a bipartisan basis.

But examining the history of the judicial wars this way, by tallying filibusters or failed nominees, is less illuminating than examining the partisan motives that have driven escalating judicial brinkmanship.

In a completely nonpartisan environment, the Senate will confirm all presidential nominees, so long as they are qualified or fit to be life-tenured judges. In an environment of elevated partisanship, the opposition party will attempt to circumscribe the confirmation process to exclude nominees they deem too ideologically extreme. In an environment of unbounded power politics, the opposition party will declare everyone a president might nominate to be out of bounds.

Bork was deemed unfit by a bipartisan majority, and both Democrats and Republicans have rejected small numbers of individual lower court nominees on the basis of alleged ideological extremism. McConnell’s innovation—where the even-handed arms race analysis breaks down—was to declare vacancies themselves off limits to the other party, and attempt to commandeer entire courts, including the Supreme Court, for conservatives.

It was McConnell’s indiscriminate filibuster of three judges in 2013—an attempt to exert sole partisan dominion over the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals—that preceded then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s decision to abolish the filibuster for lower court judges. And it was McConnell’s edict last year that Obama would not be allowed to fill the current Court vacancy, created by Justice Antonin Scalia’s death, that provides the backdrop for our current crisis. Having stolen an appointment that rightly belonged to Obama, Republicans now bemoan that Democrats won’t sanctify that theft by handing the goods to President Donald Trump and Neil Gorsuch.

McConnell is within his rights to “go nuclear,” just as Reid was. But having witnessed multiple GOP efforts to deny Democrats equal power to shape the two most powerful courts in the country, they would be foolish to remain unilaterally disarmed by helping confirm Gorsuch. Once McConnell abolishes the filibuster, the new power-uber-alles standard will be cemented, and the playing field will be leveled once again.

It is true that the new judicial politics leave us vulnerable to protracted crises, should power become divided between the White House and Senate, and confirmations grind to a halt for years at a time. But that situation is far likelier to force consensus than unilateral appeasement would do. The best liberal case against the Gorsuch filibuster rests on the hope that, if Democrats agree to confirm him, McConnell might somehow reciprocate their goodwill by preserving the filibuster when the next vacancy arises, allowing Democrats to force Trump to appoint a moderate.

This is like the fable of the scorpion and the frog, if the frog were Democrats struggling to remain afloat in Trump’s America, and the scorpion were a buoyant man-turtle. The Senate majority leader has no need for this deal; if he accepted it, it would be unenforceable; and if time came for him to make good on his commitment, he would likely welsh on it.

What will happen instead, assuming McConnell has the votes to change the rules, is that the hoary pretenses of Republican obstructionism will lose what’s left of their force, allowing everyone to see the parties for what they are.