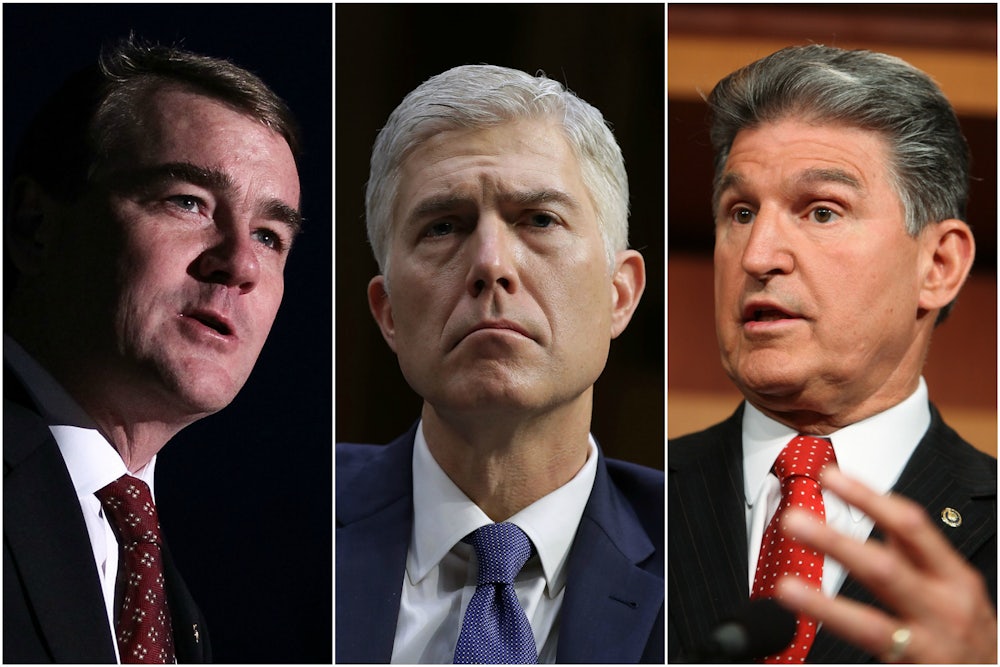

Democrats secured the votes on Monday to filibuster President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Judge Neil Gorsuch, later this week. But four of their senators—Joe Manchin, Heidi Heitkamp, Joe Donnelly, and Michael Bennet—won’t be joining in the resistance. These centrists are trying to avoid total opposition to Donald Trump, in part because they’re fearful of being punished by voters at home (especially Bennet, of Colorado, where Gorsuch is from).

The notion that opposition might imperil these senators, risking further depletion of the Democratic caucus in the 2018 midterm elections, is the only reason progressives could live with their defections. There’s just one problem. According to the former dean of the Supreme Court press corps, senators’ votes on Court nominees have seldom made a difference for them electorally.

“I honestly don’t know of any circumstance where somebody gained a seat or lost a seat in the Senate based on the position they’d taken on a Supreme Court nomination,” said Lyle Denniston, who has reported on the Court for almost six decades, including 12 years at SCOTUSblog. Even in this hyper-partisan moment, Denniston told me, “I find it very hard to imagine, with all of the other issues surrounding a senatorial election, that the Supreme Court will be decisive.”

It’s not just Denniston who sees it this way.

“I can’t think of an example of a senator who lost an election or really got into deep trouble on a Supreme Court nomination,” American Enterprise Institute scholar Norm Ornstein said. “I can’t think of one,” echoed Bob Shrum, the longtime Democratic strategist.

This may be why other vulnerable senators up for reelection next year, such as Claire McCaskill and Jon Tester, are nonetheless joining the filibuster. And it’s why Democrats should expect their senators to stand together and oppose Gorsuch: If past is prologue, they have no excuse not to.

I emailed Linda Greenhouse, the longtime Supreme Court correspondent for The New York Times, to see if she had examples of senators who lost reelection or otherwise suffered politically over a tough confirmation vote. The only one that came to her mind was the late Arlen Specter, who represented Pennsylvania from 1981 to 2011, mostly as a Republican and then briefly as a Democrat.

A pro-choice centrist, Specter infuriated the right by grilling President Ronald Reagan’s reactionary nominee Robert Bork on abortion and ultimately voting against him. Specter “certainly paid a price,” Greenhouse said, “and didn’t make that ‘mistake’ again when—still a Republican—he voted for Clarence Thomas’s confirmation a few years later.”

Ironically, Specter’s vociferous defense of Thomas put him in danger again, enraging the left when he accused Anita Hill of “flat-out perjury” over her charge that Thomas sexually harassed her. For Specter, both confirmation processes were the rare instances when a senator’s questioning and ultimate vote made a lasting difference.

“He damn near lost his seat over Thomas,” former Specter aide Charles Robbins told me. When it came to Bork, the senator proudly embraced a quote from one of the judge’s lobbyists who said Specter scored the “game-winning RBI” to defeat Bork’s nomination. There were plenty of apostasies that ultimately forced him from the Republican Party, Robbins said, but “when you compile the sins of Arlen Specter, that was the first one.”

Even so, this was a special case. Following Specter’s death in 2012, Jeffrey Toobin wrote in The New Yorker that “no Senator in fifty years had as profound an influence on the Supreme Court as he did.” And neither Bork nor Thomas actually cost him his seat.

“In my recollection, the only people who really think about punishing or rewarding people for their votes on Supreme Court nominees are conservative groups,” Denniston said. “They tend always to exaggerate their capacity to punish or reward.” That’s why Denniston doesn’t think there would be much political risk in Democrats voting against Gorsuch—even centrist senators from Trump-supporting states. “I don’t think I’d be comfortable saying flatly that they’d have no risk—that it would be a completely risk-free vote—but I don’t think it would be a decisive vote.”

“We’re talking about April of the year before the election,” Ornstein said. “Fifty things or 100 things are going to happen between now and primary season.” Ornstein said he could imagine Democrats who vote for Gorsuch might increase their chances of a primary challenge—though here, too, he’s dubious it will make a difference. “I doubt very much that this will be any kind of an election issue,” he said.

History says Manchin, Heitkamp, Donnelly, and Bennet won’t face consequences for refusing to join the filibuster of Gorsuch. But the dynamic may be different in the Trump era. If putting Gorsuch on the Court is Trump’s primary accomplishment this year, it’s possible voters will care more than usual about where their senators stand on the Supreme Court nominee. That’s all the more reason to expect Democratic senators to act like Democrats in opposing Gorsuch—and for their voters to punish them if they don’t.

Even Shrum, who bristles at talk of primary challenges and says “the only Democratic senator you’re going to get from North Dakota is Heidi Heitkamp,” is urging all Democrats to vote against Gorsuch in spite of the political risk. “Sometimes you have to cast votes because you think they’re right,” he said, “and then you go live with them.”