When did Scarlett Johansson stop seeming human? I don’t mean this as an insult, but it has been so long since Johansson played a normal character with recognizable emotional traits that she’s more machine than woman now. There is something waxen and impermeable about her. It probably started with her terrific, terrifying performance in Under the Skin, in which she plays a literal alien so distant that she allows a child to drown on a beach and doesn’t even seem to notice. But this persona has now evolved from a one-off to a signature. Johannson seems to be observing the rest of us from somewhere far away, and, all told, she doesn’t look particularly impressed.

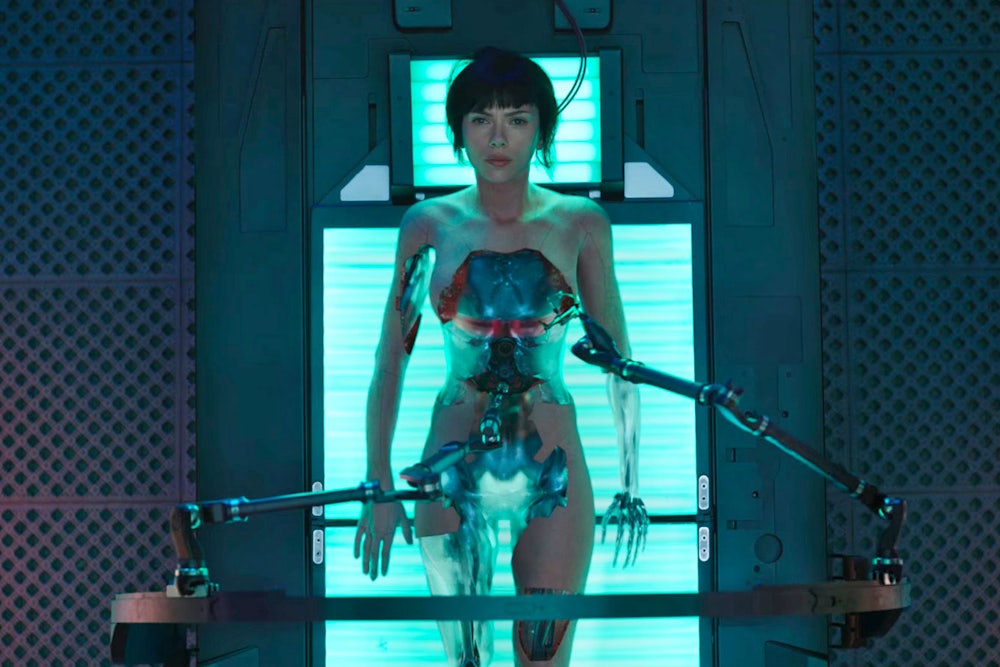

In Ghost in the Shell, based on a Japanese manga comic of the early 1990s (which inspired a fascinating 1995 animated film), Johansson plays, inevitably, a full-on robot named Major. She’s only half-robot, actually; a corporation looking to use her as a weapon took her brain and put it in the body of a super android prototype, one that is indestructible and able to destroy everything in its path, while perfectly matching the curves of professional actress Scarlett Johansson. She’s tended to by a doctor (Juliette Binoche, a wonderful actress who seems slightly confused to be here) who both works for the corporation and protects Major from it, until a hacker (Michael Pitt) digs into Major’s mainframe, learns who she is, and attempts to use her against the corporation and the state. Major then must find out her true identity and her true allies, which include a kindly old warrior (Takeshi Kitano) and something vaguely resembling a love interest (Pilou Asbaek).

Johansson’s eerie, detached quality is the best thing the film has going for it. Really, it’s the only thing that makes it interesting. The story is nothing you haven’t seen hundreds of times before, set in yet another Blade Runner knockoff universe where big cities have become techno-nightmares. Every skyline is a series of holographic advertisements and it is always, always raining. There’s a big faceless corporation that’s evil, there’s a band of honorable warriors battling to expose it, and nothing less than the future of the human race is at stake. It is Future Dystopia 101, and director Rupert Sanders (Snow White and the Huntsman) is too workmanlike to give it much visual pizzazz. There are moments of beauty, but they are almost accidental: There’s little inspiration at work here.

Johannsson can’t help but keep you watching, though. As an actress, she’s starting to resemble Keanu Reeves after all that information gets downloaded into his brain in The Matrix. All-encompassing and all-powerful, but more bewildered, even amused, by this power than invigorated by it. She’s just a little off, and it gives the movie a funky energy that works in its favor, at least for a little while. The movie is a little too self-conscious about its Cyberpunkery, and I bet a lot of its “he’s tapped into the mainframe!” dialogue won’t age well.

Sanders also seems to have no real attachment to this material. He just pillages from other, better movies, slapping it all together, finding a couple things that work, then going back to that well over and over. The movie never commits to itself, one way or the other, so it mostly just sits there, reminding you that you probably should have just watched Minority Report again, or just the original Ghost in the Shell.

Which brings us to one of the major issues surrounding the film: the “whitewashing” of the main character, a Japanese android in the original movie and the manga comic. The movie does provide a narrative reason that Major (and Pitt’s character) are white Americans surrounded by the Japanese, in a way that’s actually the only interesting psychological element to any of the characters in the film. At the risk of divulging spoilers, I’ll just say that the film finds a way to sneak in the idea of cultural appropriation being destructive … while still, of course, being a prime example of it. The reason this plot point exists is only because a white American actor was cast in the first place, and the reason that had to happen was so the film could be financed, which is the reason this shit all keeps happening anyway.

The film’s arguments against cultural appropriation feel more apologetic than sincere. That tells you most of what you need to know about Ghost in the Shell. It only works up much feeling when it is trying to defend itself against protests that might affect its bottom line. You won’t be much moved by that either.

Grade: C

Grierson & Leitch write about the movies regularly for the New Republic and host a podcast on film. Follow them on Twitter @griersonleitch or visit their site griersonleitch.com.