Claire McCaskill, the Democratic senator from Missouri, is wavering on whether to support President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch, who is up for a vote on April 7. In a closed-door meeting with party donors, she said that there “is enough in his record that gives me pause…so I am very comfortable voting against him,” and acknowledged that many of her supporters wanted to fight his nomination because the Republicans refused to consider President Barack Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland. But McCaskill also admitted she’s “uncomfortable” that, by filibustering Gorsuch, she would be “part of a strategy that’s going to open up the Supreme Court to a complete change.”

The “change” she refers to is the so-called nuclear option: A change in Senate rules to require only a 51-vote majority, rather than a 60-vote supermajority, for the confirmation of Supreme Court nominees. If the Republican majority deploys that option, Democrats won’t have any tools to resist future Court picks under Trump.

“So they move it to 51 votes and they confirm either Gorsuch or they confirm the one after Gorsuch,” McCaskill argued. “They go on the Supreme Court and then, God forbid, Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies, or (Anthony) Kennedy retires or (Stephen) Breyer has a stroke or is no longer able to serve. Then we’re not talking about Scalia for Scalia, which is what Gorsuch is, we’re talking about Scalia for somebody on the court who shares our values. And then all of a sudden, the things I fought for with scars on my back to show for it in this state are in jeopardy.”

McCaskill might be justifying an unpopular vote to her supporters, but the bind she describes is undeniable: Democrats have no good options when it comes to Gorsuch. They’re damned if they do confirm him, and they’re damned if they don’t. The same is true, more broadly, of Democrats minority power, such as it is. While some consider Republicans’ dogged obstructionism under Obama to be a proven, effective model for Democrats in the Trump era, this overlooks an essential difference between the two party’s agenda: Conservatives, per their name, have a much easier time saying “no.” An escalation of partisan warfare in Washington would have serious, long-term consequences for both parties, of course. But Democrats’ progressive agenda would suffer much more for it.

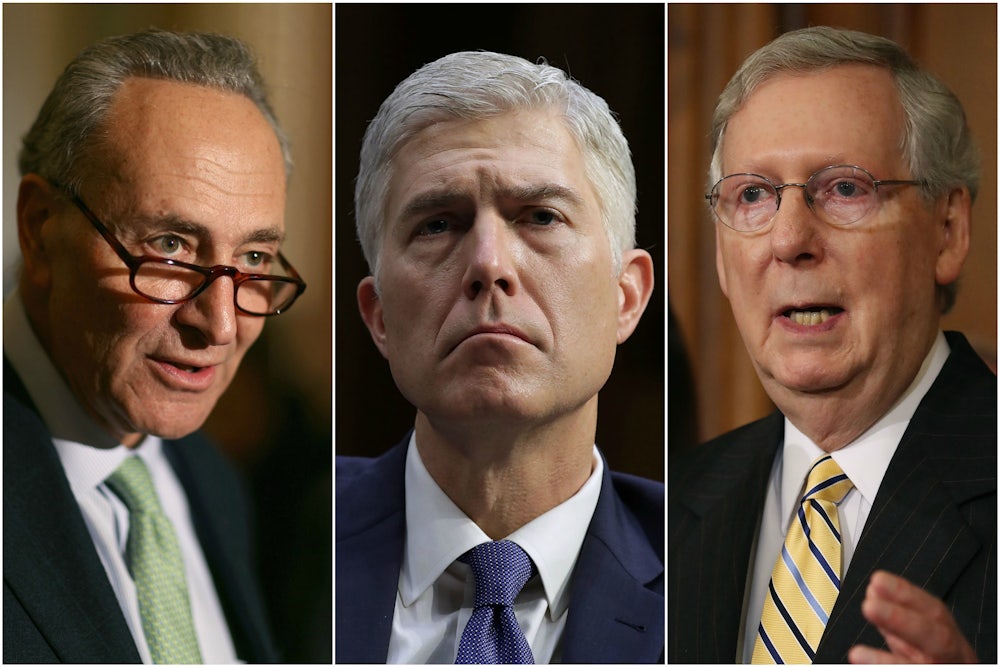

When Senate Republicans blocked Garland’s nomination last year—refusing even to allow hearings, let alone an up-or-down vote—they argued that Obama was a “lame duck president” and therefore shouldn’t have the power to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia. “The American people are perfectly capable of having their say on this issue, so let’s give them a voice,” Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said on March 16, the day Garland was nominated—and nearly eight months before the presidential election. “Let’s let the American people decide. The Senate will appropriately revisit the matter when it considers the qualifications of the nominee the next president nominates, whoever that might be.”

If Democrats cave without a fight, they are essentially validating the GOP’s obstructionist strategy. Even moderate Democrats find that intolerable. “I have a very hard time getting over what was done to Merrick Garland, a very hard time,” Senator Thomas Carper of Delaware told The Washington Post on Tuesday. “That’s a wrong that should be righted, we have a chance to do that, and it won’t be by confirming Judge Gorsuch the first time through.” Doing so would also further infuriate the party’s progressive wing, which is still smarting from Tom Perez’s victory over Congressman Keith Ellison for chair of the Democratic National Committee.

But if Democrats filibuster Gorsuch, Republicans almost surely will eliminate the Supreme Court exception that then-Majority Leader Harry Reid, facing obstruction by the Republican minority in 2013, created when he deployed the nuclear option to confirm some of Obama’s executive-branch and appeals-court nominees. This change in Senate parliamentary rules, a likely permanent one, will only intensify the scorched-earth, zero-sum tactics on Capitol Hill—an increasing polarization that will make it even more difficult for Democrats to govern the next time they are in power.

McConnell, more than anyone, is responsible for the Democrats’ dilemma—not just for the decision to stonewall Garland, but Republicans’ broader strategy of obstruction at all costs. As minority leader, he crafted the strategy after Obama’s win in 2008, and the policy is still sending shockwaves through Washington—especially now that Democrats, as the opposition party, are forced to decide whether to imitate McConnell’s tactics. “This strategy of kicking the hell out of Obama all the time, treating him not just as a president from the opposing party but as an extreme threat to the American way of life, has been a remarkable political success,” Michael Grunwald argued at Politico last December. “It helped Republicans take back the House in 2010, the Senate in 2014, and the White House in 2016.”

This is probably the most expedient path for Democrats: To become the new “party of no.” With a riled-up Democratic base, and a president that is much more unpopular than Obama ever was, this strategy is likely to reap political dividends in the 2018 midterms and the 2020 presidential election.

The problem for Democrats is how to make Washington governable again, if and when they return to power. The supermajority threshold is—or was—key to fostering comity in the Senate. “The purpose of the rule is to promote bipartisanship and consensus, which, in turn, creates legitimacy and buy-in for policy and governance,” the Post’s Paul Kane wrote on Wednesday. “If the filibuster goes away, so does yet another layer of collegiality in Congress—and another way to shore up Washington’s credibility.”

Democrats might be delighted that the polarization McConnell fostered is now tearing apart the Republican Party, as hardliners from the House Freedom Caucus battle Trump with almost as much ferocity as they battled Obama. The Republicans have made Washington so dysfunctional, they can’t even reach agreements with each other now that they are the majority party. It’s notable that in the following tweet on Thusday, Trump treats Democrats as an afterthought:

The Freedom Caucus will hurt the entire Republican agenda if they don't get on the team, & fast. We must fight them, & Dems, in 2018!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 30, 2017

But this sort of dysfunction hurts the Democrats more than Republicans in the long run. Domestically, the Republicans have an essentially negative agenda, one centered around cutting programs and dismantling laws. If government isn’t functioning, then so much the better: It makes the case against taxes and regulations that much easier. Democrats have a constructive, positive agenda that aims to strengthen the safety net, broaden health care coverage, make college education more affordable, and protect the environment and human health. A dysfunctional Washington hampers all of these efforts, which, barring a massive and unexpected shift in the electoral landscape, would require some degree of bipartisanship.

Mitch McConnell, the lead architect of a permanently gridlocked Washington, should be pleased with his handiwork. It may be causing problems for his party right now, but no matter. It’s all part of conservatives’ grand plan to convince every American that government is always the problem, and never the solution.