For Democrats, the one great policy legacy of 2016 was the party’s embrace of free tuition for public colleges and universities. After Bernie Sanders made it a signature policy proposal and proved its political potency (especially with millennials), Hillary Clinton adapted and adopted it when she won the nomination. Over the course of the campaign, the idea evolved from a progressive pipe dream into a concept with massive momentum. This thing was going to happen!

But when Donald Trump won and Republicans took control of Congress, a federal free-tuition program became a pipe dream again. The only chance for free college was to start at the state level—in one of the few remaining blue states—and create a model that could spread nationally. Given the popularity of the idea, it’s not surprising that two ambitious Democratic governors–both presidential prospects for 2020—have taken up the call.

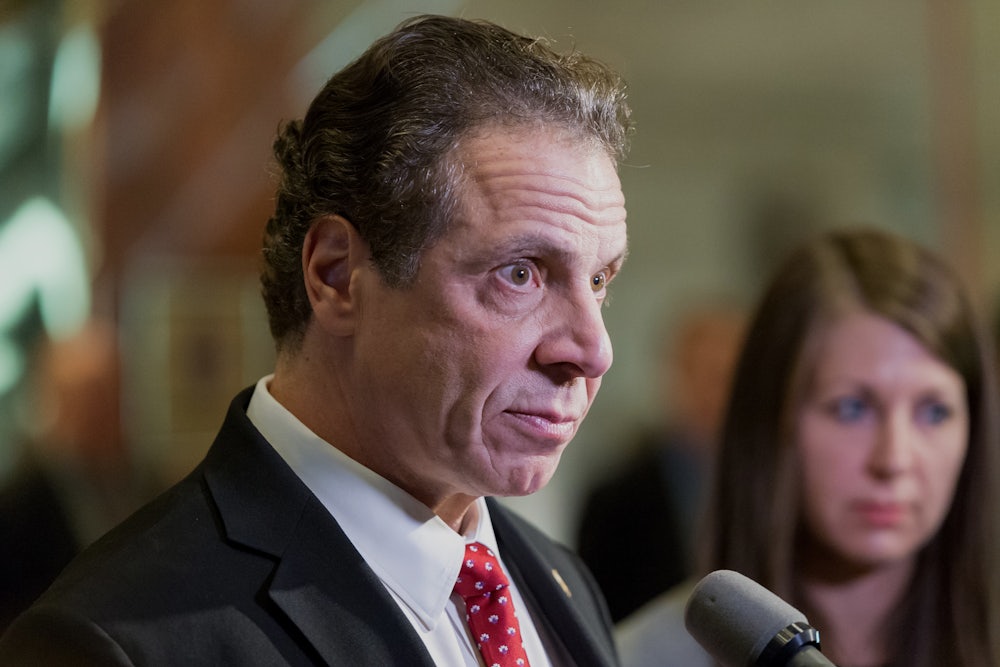

Both New York’s Andrew Cuomo and Rhode Island’s Gina Raimondo are vying to be the governor who made free college happen—and both their plans are running into resistance from their own party’s lawmakers. Some of the controversy was to be expected: It’s no surprise that fiscal conservatives think it’s another costly social program with uncertain returns. Other legislators and educators worry about how it will affect enrollment at state schools.

But for liberals, the legislative battles have exposed a series of tricky policy trade-offs that cut to the heart of a larger national debate: What kind of “progress” should Democrats be fighting for? Should a new social program benefit everyone equally, like Social Security, or help low-income families the most? And how valuable is tuition relief, really, if the state doesn’t help students with other college expenses, like room and board and books?

The surface simplicity of the whole idea is one of its great calling cards: Free college. How complicated could that be? The debates in New York and Rhode Island have sometimes been acrimonious and divisive. But that’s far from a bad thing: Democrats will ultimately have to hash through some complicated questions to forge a viable free-college model for the country. Why not start in New York and Rhode Island?

Cuomo unveiled his free-tuition program on January 3 with great fanfare—and with Bernie Sanders on hand to help sell it. Cuomo’s plan would cover every in-state student at two- or four-year public colleges whose families make less than $125,000 a year. Sanders hailed the initiative as “a revolutionary idea for higher education,” and vowed: “If New York State does it this year, mark my words, state after state will follow.”

Not two weeks later, Raimondo rolled out her own proposal. Her plan has no income cap—families with incomes above $125,000 are included. It covers two years of free tuition at her state’s public institutions—both years at the Community College of Rhode Island, or the last two years at the University of Rhode Island or Rhode Island College. The $30 million plan is structured to raise graduation rates, on the theory that funding the last two years will prevent financially struggling four-year students from dropping out—often with a bunch of debt—halfway through their education.

One prominent progressive commentator recently suggested Raimondo follow Cuomo’s lead and means-test her program. “But the reality is that means-testing would leave out too many middle-class families,” Raimondo wrote early this month in a blog post for the Campaign for Free College Tuition. Her office pointed out that, under Cuomo’s $125,000 income cap, a family of three making $124,000 would qualify for free tuition, while a family of six making $126,000 wouldn’t.

That’s the first key distinction between the plans, and experts say they both have merits. “If you make it free for everyone,” said Seton Hall University professor Robert Kelchen, “then wealthy people benefit, and they don’t need the money to go.” At the same time, Kelchen said, “If you try to target more narrowly, you run the risk of needy students not thinking they’re eligible, or not hearing about the program.”

That might sound like a strange argument in favor of Raimondo’s approach: You’d expect the case for including well-off families would be philosophical or political—that it’d be all about making sure “free college” can’t be cast as another “handout” to lower-income Americans, and become another political wedge issue for Republicans to wield. But a major problem in higher education is students, especially those from low-income families, not knowing what aid is available to them. That’s why Matthew Chingos, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said there’s marketing value to making a free-tuition program universal. In practical terms, he said, “The question is whether it’s enough to justify the cost of making it free for people who don’t need it to be free.”

Another question is how much the Cuomo and Raimondo plans will truly benefit low-income students. Both proposals are what’s called “last-dollar” initiatives, meaning the states would only pay the balance of tuition after students use up existing state and federal aid, including Pell Grants. These current state and federal programs couldn’t be used to fund other college costs.

This approach stands in contrast to “first-dollar” plans that Sanders and Clinton proposed at the federal level. They would have fully funded tuition for all eligible students up front, freeing up current aid programs for use on those other expenses. “The difference between first-dollar and last-dollar is pretty big and fundamentally changes how progressive a plan is,” said Mark Huelsman, a senior policy analyst at the liberal think tank Demos. He stressed that non-tuition costs are “a big area of college affordability that students face—it’s a huge driver of the student-debt crisis.”

Chingos went even further: “People who consider themselves progressives should be less sympathetic to the New York and Rhode Island plans than they were to the Clinton and Sanders plans.”

Still, there’s an obvious, pragmatic reason for governors to pursue the last-dollar approach: It’s much cheaper. “From a state perspective, last-dollar makes all the sense in the world, because then you’re having the federal government pay a lot of the price,” Kelchen said. In New York, at least, “it’s just the only way they can make the numbers work,” he added. Cuomo says his program will cost $163 million a year. Kelchen said that estimate is likely low.

Cuomo is taking flak from all directions. Some Democrats in New York want to increase Cuomo’s income cap to $150,000, to include more “middle-class” families, while providing low-income students help with room and board. The Republican-controlled Senate, meanwhile, wants to ditch his plan altogether and focus on investing in the state’s Tuition Assistance Program. That initiative funds private as well as public colleges, many of which—surprise!—oppose Cuomo’s plan.

“The private college lobby is strong, and they’re nicely spread among the state in different legislative districts,” Kelchen said. And when they claim that free public college will spike the price of a private college education for New York students, they may have a point, Chingos said: “If you change the relative price of something, it’s Econ 101 that people’s demand for it will change as well.”

But should private-school tuition be a priority for a program intended to benefit kids who can’t afford even public schools? Maggie Thompson, executive director of the liberal group Generation Progress, likens the private schools to the insurance interests during the Affordable Care Act fight. This time, will Democrats hinge “reform” on keeping the marketplace happy, or do what’s best for the people? “I actually think there’s a lot of parallel with the health care fight,” she said. “I view this as like the public option.”

As Bernie Sanders is fond of saying, free public tuition isn’t a radical idea—or at least it shouldn’t be. It was the reality in many states, California included, until recent history. And there’s a related, bipartisan movement across the country for tuition-free community college—an initiative championed by former President Barack Obama that continues to flower in states and localities.

If the Cuomo and Raimondo plans emerge from budget negotiations currently underway, other states will have two more important models to build on. But liberals in other states—and eventually in Congress, when Democrats win it back—won’t want to follow either roadmap blindly. As Chingos said, the concessions to middle-class (and upper-class) families “raise the concern that the drift is in helping politically vocal middle-and-upper-middle-class families as opposed to doing more for lower-income families.”

Democrats will continue to face hard choices on these issues. That’s what happens when you take a “radical” idea and try to make it happen. But the debates in New York and Rhode Island, ultimately, show that free college is moving forward the way it should, being hashed out in the “laboratories of democracy.” As Huelsman said, “it’s really nice to see states taking it upon themselves to do something, even if they feel cost-constrained. It shows the idea isn’t going away anytime soon.”