In his poem “Jean Rhys,” from the 1982 collection The Fortunate Traveller, Derek Walcott imagines Rhys’s childhood in Dominica, a Caribbean island just a hop and a step away from Walcott’s own Saint Lucia. Though Rhys was a white woman, and would leave the West Indies for good when she came of age, spending the rest of her unhappy life in self-imposed exile in Europe, Walcott sees her as a kindred spirit. The Atlantic Ocean, for the young Rhys, is but a “rumorous haze behind the lime trees”; England, another rumor, is the “arches of the Thames” and “Parliament’s needles” sewn in petit point on hammock cushions that grow faded in the tropical sun.

The girl herself is both there and not. She lives profoundly in each moment, as only the young can: “Sundays! Their furnace/of boredom after church.” But her sigh is like “the white hush between sentences” in a book—blank as an event unrecorded, lost to oblivion. It is as if her true self lies elsewhere, not in Dominica or England per se, nor in the sallow photographs of the time, but in the work she would go on to create:

a child stares at the windless candle flame

from the corner of a lion-footed couch

at the erect white light,

her right hand married to Jane Eyre,

foreseeing that her own white wedding dress

will be white paper.

This is a reference to Rhys’s most famous novel, Wide Sargasso Sea, a postmodern tale told from the perspective of Bertha, Charlotte Brontë’s madwoman in the attic. Sargasso’s publication in 1966 rescued the 76-year-old Rhys from an obscure existence in the English countryside, and revived interest in a body of work that had been forgotten, but of her newfound fame Rhys would say, “It has come too late.” Alcohol had ravaged her life. So had her three actual marriages, to men who served as the inspirations for the men in her fiction, a louche and unfaithful lot. We might include in their company the novelist Ford Madox Ford, who was an early champion and mentor (it was Ford who told her to adopt the pen name by which we know her) but also her seducer; their affair, which devastated her, was the inspiration for the novel Quartet. “I think if I had to choose I’d rather be happy than write,” she told an interviewer. “If I had my life all over again and could choose.”

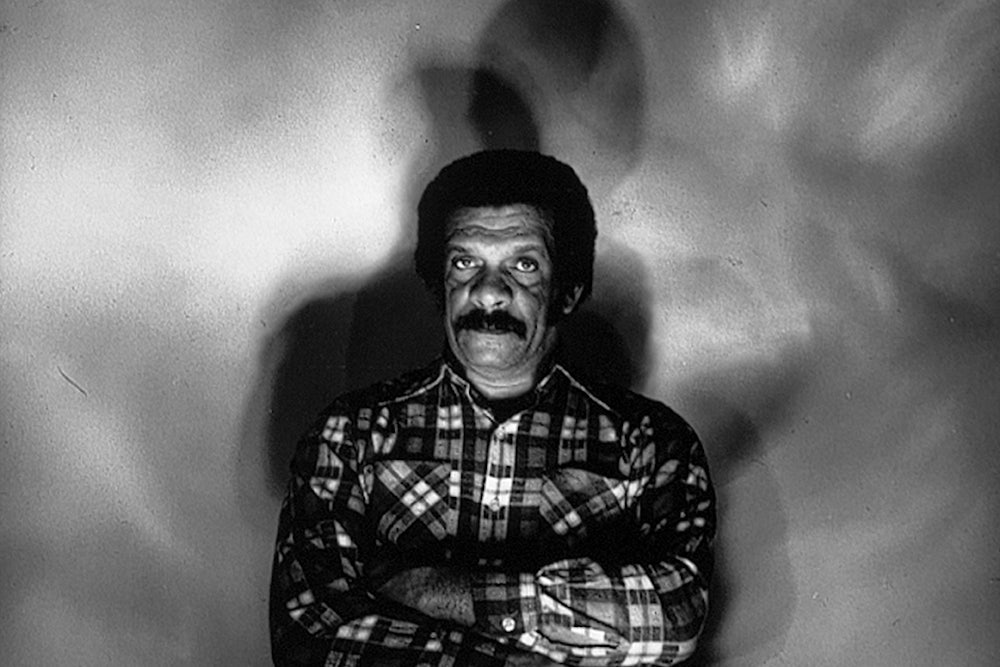

It is telling that, when confronted with the work and the life, Walcott emphasizes the work, Rhys, the life. For Walcott, it sometimes seems as if all of life is what passes “through your pen’s eye,” as he wrote in the poem “Exile”—what is transformed into word and image. The artist is a vessel for life, which would otherwise drain away into the white abyss between words, and for that we revere him. But when I asked a colleague about Walcott last Friday, the day he died, she replied that Walcott was a “literary great” but “a bad person,” as if the two things were of equal weight. More damningly, she meant that they cancelled each other out. When I told my wife about this exchange, she said, “Good. I am tired of revering these men.”

They were both responding to multiple allegations of sexual harassment that erupted into the open in 2009, forcing Walcott to withdraw his candidacy to be the professor of poetry at Oxford. One former student at Harvard had accused Walcott of punishing her with a C grade for her poetry, which he called “formless, rhythmless, and incomplete,” after she refused to sleep with him. Another former student, Nicole Kelby, said he threatened to block the production of her play unless she acquiesced to sex. Kelby filed charges against him, charges that were rejected by both Walcott and Boston University. (One school official defended him by saying, “The way one teaches poets and playwrights and fiction writers is different than the way one teaches mathematics students.”) The scandal destroyed Kelby’s marriage. She was ostracized by old friends. Male employers treated her suspiciously. “Practically every man I met was worried I was going to sue him for sexual harassment,” she told The Daily Mail. She settled her case against Walcott in 1996, without him or the university admitting wrongdoing.

These kinds of debates can admittedly be tiresome, and are nearly as old as literature itself. Dickens left his wife for a younger woman, Faulkner was a mean old misogynist—we read them anyway. So far, Walcott’s admirers need not worry about his legacy. His obituary in The New York Times made only a perfunctory reference to the 2009 scandal, pushing it to the very bottom of the story as if it were an embarrassing smell. The Washington Post did the same. But the balance of coverage is bound to shift over time. Since these allegations resurfaced less than a decade ago, a sea change has occurred in our cultural politics. It is no longer as easy for great men to hide their offenses behind the magisterial cloak of their art. Nor are they spared harsh judgment merely because they lived in earlier, less enlightened times. Nicole Kelby and Jean Rhys were the victims of a literary patriarchy that stretches back centuries, that extends unbroken from Ford Madox Ford to Derek Walcott.

We can see this revisionary treatment occurring in all fields, from politics to cinema. Thomas Jefferson has fallen in our esteem, in large part because of new revelations about his relationship with his slave mistress Sally Hemings; “the third president was a creepy, brutal hypocrite,” as one historian wrote in 2012. John F. Kennedy’s star has also fallen, after many decades in which his womanizing was seen as a pillar of his mystique. Roman Polanski’s conviction for statutory rape, far from being consigned to the druggy fog of the 1970s, has only grown more troubling with time. The ethics of watching Woody Allen movies is a source of fraught debate, while even a universally beloved artist like David Bowie has been questioned for his relationships with underaged women. The scales we use to judge the reputations of these men, with the life weighed on one end and the work on the other, have started to tip.

This raises all sorts of complications. It is hard to imagine many writers in history surviving the unforgiving scrutiny of contemporary cultural politics—which, it should be said, is a relatively new phenomenon whose influence could very well wane. It has yet to withstand the test of time, as the works of Dickens and Faulkner have. But it is particularly problematic when you consider a figure like Walcott, who shot to global prominence not only because of the pure flame of his genius, but because he was giving voice to people who had been ignored and exploited and enslaved by a dominant culture. He did it with the language he inherited from the colonizer, within the Western tradition that was foisted upon him, claiming all its literature as his patrimony even as he infused it with his own motley identity, thereby changing it forever.

The affinity he showed for Rhys is one that others in the West may have not felt, may not have even properly understood, which seems to me to be the animating force of that poem. It echoes a passage from Another Life (1973), his great autobiographical work, in which he writes of the inner toll that comes from being outside the West, and how this estrangement seeps into the very texture of the trees, into moonlight:

The moon came to the window and stayed there.

He was her subject, changing when she changed,

from childhood he’d considered palms,

ignobler than imagined elms,

the breadfruit’s splayed

leaf coarser than oak’s,

he had prayed

nightly for his flesh to change,

his dun flesh peeled white by her lightning strokes!

When Derek Walcott writes about Jean Rhys, he is writing about her response to the hegemon whose long shadow darkened their island specks in the Caribbean. If she is sympathetic to Bertha’s madness, to her all-consuming rage toward the English men who have caged her, then so is Walcott. In this respect, his politics is intersectional. And their approach was the same: To alter the reigning culture from within, to create a mirror that exposed its hypocrisies and prejudices, to make it their own. But by degrading women in his own life, Walcott falls into an intersectional trap, forcing one claim of liberty to be pitted against another.

Again, we return to the question of life and its worth. It would be inhumane to say that art matters more than the life of Jean Rhys or Nicole Kelby. It would be self-defeating, too, for I am not free unless these women are free as well. But to affirm this comes at a cost. It means that art—that space where our mortal condition approaches the immortal, where our myriad flaws form a fertile ground for empathy—cannot redeem Walcott for his behavior. It means that we should not look to it to redeem ours, either.