In one of her poems, Emily Dickinson divides the things of the world into those that fly (“Birds -- Hours -- the Bumblebee”) and those that stay (“Grief -- Hills -- Eternity”). The division might be applied to poets. Dickinson herself was notoriously a stayer, and so in their different ways were Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, and -- once he’d found a resting place in New England -- Robert Frost. Among the poets of flight, one thinks of Eliot and Pound, and of Elizabeth Bishop, who split her time between Boston and Brazil.

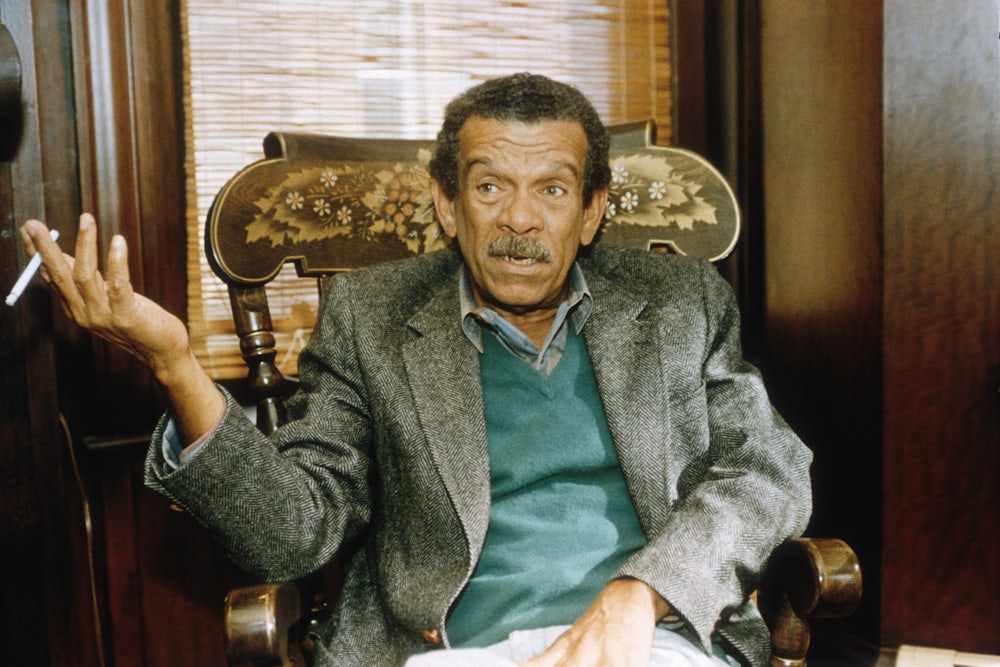

Bishop especially took what she called “questions of travel” as her province, and the same could be said of the sometimes Trinidadian, sometimes Bostonian Derek Walcott. Among his footloose titles are “The Fortunate Traveller,” “The Schooner Flight,” “North and South” (the name, it happens, of one of Bishop’s books as well). Travel, its initial release and eventual travail, has been Walcott’s theme from the beginning. He has portrayed himself again and again as a poet caught between two worlds. “Between” is perhaps the key word in his poetry. One could make a plausible argument that he is by now as much a poet of the United States as of the Caribbean. His distinctive voice, sardonic and celebratory by turns, has entered the resources of our language and literature.

Walcott and his twin brother were born in 1930 on the island of St. Lucia, in the former British colony of the Windward Islands (Lesser Antilles). Their father was an amateur painter who died before the twins were one year old. Painting was Walcott’s first choice of a career (this chapter of the growth of the poet’s mind is vividly described in Walcott’s long autobiographical poem of 1973, Another Life), and his poetry has always appealed as much to the eye as to the ear. His schoolteacher mother ensured that he got what he called “a sound colonial education.” His religious upbringing was Methodist -- “The passionate, pragmatic/Methodism of my infancy.” There has always been a tension in Walcott’s poetry between a plain-speaking, lower-church language (he admires such subtle and unemphatic poets as Edward Thomas and Thomas Hardy) and the more flamboyant verbal fireworks of the largely Catholic (and French-speaking) culture he grew up in. Grandson of two white men and two black women, he has written of himself as a “divided child,” nourished on one side by the Caribbean culture of illiterate fishermen and educated on the other by the empire-building British.

As a consequence, Walcott has never ceased asking the barrage of questions that concludes his famous early poem of 1962, with its richly ambiguous title, “A Far Cry from Africa”:

I who am poisoned with the blood of both,

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how

choose

Between this Africa and the English

tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

How can I face such slaughter and be cool?

How can I turn from Africa and live?

By the time Walcott wrote his great poem “The Schooner Flight” in 1979, he had come to see this division as cause for celebration. His narrator, who is cool and African, proclaims in deliberate patois:

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

For Walcott’s appropriating imagination, the temptation has been to see his native island in European terms (remembering forgivingly, as he does in an early poem, that “Albion too was once/A colony like ours”), to establish correspondences between a Caribbean present and a classical, European past. Homeric parallels especially intrude early and late, as when, in another Life, Walcott finds himself comparing his hometown of Castries on St. Lucia to ancient Troy, while Helen becomes a local prostitute:

Janie, the town’s one clear-complexioned

whore,

with two tow-headed children in her tow,

she sleeps with sailors only, her black

hair electrical

as all that trouble over Troy...

In the same poem Walcott wryly defends such attributions of epic importance, claiming the liberties of youth:

Provincialism loves the pseudo-epic,

so if these heroes have been given a stature

disproportionate to their cramped lives,

remember I beheld them at knee-height,

and that their thunderous exchanges

rumbled like gods about another life . . .

More recently, however, he has seemed bent on exorcising the epic, as though to purge his birthplace of meanings imposed, like governors, from the outside. In a poem called “Greece” from The Fortunate Traveller (1981), written when he had just turned 50, Walcott imagines the classical corpus of texts as a bleeding body he’s carrying to burial:

The body that I had thrown down at my

foot

was not really a body but a great book

still fluttering like chitons on a frieze,

till wind worked through the binding of its

pages

scattering Hector’s and Achilles’ rages

to white, diminishing scraps, like gulls that

ease

past the gray sphinxes of the crouching

islands.

The passage bristles, like many of Walcott’s, with implicit puns, on “corpus” and “corpse”; but also between the words “frieze” and “wind” one hears the unspoken “breeze.” The unbound pages opening like birds’ wings constitute the sort of textual metaphor that has proliferated in Walcott’s recent work. From Omeros: “the calligraphy of swallows” and the “flotilla of swallows memorizing an alphabet.” In a baroque mirroring, birds are books and books are birds.

No poetic gesture, of course, is more American than the banishing of epic. Poe in 1850 denounced what he diagnosed as “the epic mania” in the United States, especially acute in Longfellow and his fellow travelers, and proclaimed that a long poem was “simply a flat contradiction in terms.” Whitman invited the muse to “migrate from Greece and Ionia,” leaving her baggage behind: “Cross out please those immensely overpaid accounts,/That matter of Troy and Achilles’ wrath, and Aeneas’, Odysseus’ wanderings . . .” While American poets like to make a big show of banishing the epic muse, however, they are just as likely to let her in by the back door. Whitman wanted his muse to put Parnassus up for rent, and take up residence “amid the kitchen ware” -- a rather servile position, one might think, though perhaps with its own subversive possibilities. (In another Life, Walcott wrote that he “had entered the house of literature as a houseboy.”)

In Walcott’s new and very long poem Omeros, epic ambitions resurface with a vengeance. The poem was conceived, he informs us, in an erotic encounter between the narrator-poet and a Greek girlfriend who pronounces the name of her national poet in the Greek fashion: “Omeros.” “Homer and Virg are New England farmers,” Walcott counters dismissively, “and the winged horse guards their gas-station.” But the seductive pull of verbal association has him in thrall:

I said, “Omeros,”

and O was the conch-shell’s invocation, mer

was

both mother and sea in our Antillean

patois,

os, a grey bone, and the white surf as it

crashes

and spreads its sibilant collar on a lace

shore.

“I miss my islands,” says the Greek woman, and so does Walcott, who returns to repeople his own with epic characters.

It is precisely “amid the kitchen ware” that the poet finds his Helen: she is the maid in a household of British colonialists called the Plunketts. Like her classical counterpart, Helen is married to one man but sleeps with another. Her husband, Achille, the hero of Omeros, is a fisherman who spends his days in a canoe called “In God We Troust.” Her lover Hector has traded in his canoe for a taxi. While Achille lives in the older world of natural rhythms -- wind, sand, surf, and stars -- Hector has embraced the new world of tourism and speed. The quarrel between the two fisherman/warriors is also a quarrel between past and present, tradition and modernity, Africa and Europe.

Walcott fills out his cast of characters with a local blind bard called St. Omere, nicknamed (or rather brandnamed) “Seven Seas,” and a fisherman called Philoctete whose leg has been scarred by a rusted anchor. (Actually there are two Philoctetes characters in Omeros, for Plunkett is suffering from an ancient head wound. “This wound I have stitched into Plunkett’s character,” Walcott’s narrator says in a self-conscious and illusion-breaking moment. “He has to be wounded, affliction is one theme/of this work, this fiction . . .” Stitched, too, are the linked sounds of “stitched . . . affliction . . . fiction.”)

To summarize the plot of Omeros would be tedious and misleading, for the life of the poem lies not so much in the amorous intrigues of the characters, who remain rather hypothetical and stereotyped. The book is better read as a sort of fantasy on Homeric themes, a complex instrument by which Walcott can follow freely the associations of name and history that any given character allows him. Some of these imaginative journeys, it seems to me, are misguided -- for example, the bathetic trips to the American West and South, when Walcott hammers home the familiar ironies of a nation founded on freedom that indulged in genocide and slavery: “all colonies inherit their empire’s sin,/and these, who broke free of the net, enmeshed a race.” I could also have done without the journey to Ireland, as Walcott follows his character Maud Plunkett back to her ancestral County Wicklow, and weaves a medley on Irish themes, including the recent Troubles.

More convincing is the evocation of Achille, marooned on an island and hallucinating in the sunlight, who imagines himself retracing the “middle passage” of manacled Africans, walking “for three hundred years/in the silken wake like a ribbon of the galleons.” In a fine Sophoclean hymn to man as maker, Walcott finds the roots of artistic creation in the manacles of enslavement:

The worst crime is to leave a man’s hands

empty.

Men are born makers, with that primal

simplicity

in every maker since Adam. This is pre-

history,

that itching instinct in the criss-crossed net

of their palms, its wickerwork. They coul

not

stay idle too long. The chained wrists

couldn’t forget

the carver for whom antelopes leapt, or

the bow-maker the shaft, or the armourer

his nail-studs, the shield held up to Hector

that was the hammerer’s art.

Walcott’s writing is at its tactile best in such passages, the alliterative weaving of “that itching instinct in the criss-crossed net/of their palms, its wickerwork.” The men wait in the hold of the slave ship, each one carrying “the nameless freight of himself to the other world,” until they arrive at “dry sand their soles knew. Sand they could recognize.”

In a pivotal Dantesque scene, Walcott encounters the shade of his father, who points to a line of women carrying baskets of coal on their heads to load onto a ship. Walcott’s father finds in this task a metaphor for the writing of poetry:

Kneel to your load, then balance your

staggering feet

and walk up that coal ladder as they do in

time,

one bare foot after the next in ancestral

rhyme.

Because Rhyme remains the parentheses

of palms

shielding a candle’s tongue, it is the language’s

desire to enclose the loved world in its

arms;

or heft a coal-basket; only by its stages

like those groaning women will you

achieve that height

whose wooden planks in couplets lift your

pages

higher than those hills of infernal

anthracite.

The son’s duty, Walcott p]re concludes, is “to give those feet a voice.” The scene might be compared, for uncanny power, with Seamus Heaney’s central poem in which, watching his father toiling with a spade, he grasps his squat pen and says, “I’ll dig with it.”

The “feet” that Walcott has chosen for Omeros have epic ambitions as well. The loose terza rima, borrowed from the Divine Comedy, accommodates a great variety of rhyming -- off, near, and the sort of consonantal rhyming so dear to Wilfred Owen. Standing in the printery that was once his house, Walcott has a vision of his mother sewing:

The hum

of the wheel’s elbow stopped. And there

was a figure

framed in the quiet window for whom this

was home,

tracing its dust, rubbing thumb and

middle finger,

then coming to me, not past, but through

the machines.

But Walcott’s choice of meter (“Time is the metre, memory the only plot”) is a strange one. There have been many experiments in translating Greek and Latin hexameters into English. Poe himself attacked Longfellow’s attempts, and Richmond Lattimore’s translation of the Iliad may be the best-known contemporary example. But Walcott has not adopted the familiar practice of adding another stressed foot to an iambic pentameter line. Instead, he has opted for a line of twelve syllables (with occasional fudging) and varying rhythm.

This seems, to my ear, an odd solution. Syllabic verse, in Marianne Moore for example, depends for its effects on variation in line-length, thus playing with the expectations of ear and eye. But it’s hard to hear the twelve syllables in line after line without flattening one’s sense of their natural emphasis. The invocation, “O open this day with the conch’s moan, Omeros,” is wonderful in its five-beat, anapest-decelerating-to-iambic grandeur (amplified by a thirteenth syllable). But how is one meant to hear lines like these, from Achille’s African journey?

So loaded with

his thoughts, like a net with the clear

and tasteless to him river-fish, was

Achille -- so dark

that the fishermen avoided him. They

brewed a beer

which they fermented from a familiar bark

and got drunk on it . . .

The rhythm wavers every which way -- mimicking drunkenness perhaps? -- and is not helped by the awkward adjectival phrase “clear and tasteless to him river-fish.”

I would have welcomed more of the sort of formal variation that Walcott allows himself only rarely in Omeros, for example in the wonderful lyric that follows his description of finding himself shipwrecked in a Brookline “of brick and leaf-shaded lanes.” The bruising trochaic tetrameters begin:

House of umbrage, house of fear,

house of multiplying air

House of memories that grow

like shadows out of Allan Poe

House where marriages go bust,

house of telephone and lust

House of caves, behind whose door

a wave is crouching with its roar

House of toothbrush, house of sin,

of branches scratching, “Let me in!”

In such passages one detects the lineaments of a different poem, and in some ways a more ambitious one, in which Walcott is less determined to follow every cultural “rhyme” in his Antillean conflict, less intent on playing out its implications in his relentless hexameters. I suspect there will be other readers who find, as I did, that such layered weaving of divergent cultures becomes exasperating after a while. (Walcott associates Creeks -- the Indian tribe -- with Greeks, Homer’s Achilles with Winslow Homer’s shark-eluding, Achille-like fisherman in the great painting The Gulf.) I found myself looking forward to those moments in the poem when Walcott speaks, as he does in the Brookline sections, in what one has come to think of as his own voice, the world-weary but still wary voice of his book Midsummer (1984). It is the voice one hears in the epilogue of Omeros:

I sang of quiet Achille, Afolabe’s son,

who never ascended in an elevator,

who had no passport, since the horizon

needs none,

never begged nor borrowed, was nobody’s

waiter,

whose end, when it comes, will be a death

by water

(which is not for this book, which will remain unknown

and unread by him). I sang the only

slaughter

that brought him delight, and that from

necessity

-- of fish, sang the channels of his back in the

sun. I sang our wide country, the Caribbean

Sea.

In his sixtieth year Derek Walcott has reached that stage of eminence when his greatest danger is to repeat himself. (If certain cardinals are said to be papabile or “Popeable,” Walcott surely is Nobelable.) Omeros is a poem of great ambition, and yet it lacks the surefootedness and the verve of what remains Walcott’s masterpiece, “The Schooner Flight.” In trying to hold all the strands of his art in the palm of his hand, he has allowed some of them to slacken. Yet it’s possible that in singling out certain passages for praise, one runs the risk of missing the forest for the pleasure afforded by a few shade trees. (Dante’s first readers probably thought that he had managed a few good cantos in the Commedia.) Omeros has the sheer abundance and generosity one has come to expect of Walcott, and that is sufficient cause for celebration.